Background: Private wing service in public hospitals was established in Ethiopia in 2009. The main objective of the private wing was to motivate and retain specialist doctors. Retention of doctors had been a big challenge for Ethiopian public hospitals. This study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of the private wing in St. Paul Hospital.

Methods: This is a qualitative study based on Focus group discussions, key informant interviews were conducted with specialist doctors, nurses, anesthetists and members of the hospital management team and document review was made. Data were collected in December 2015 to January 2016. All data were transcribed verbatim, typed and stored safely. Content and thematic analysis was done.

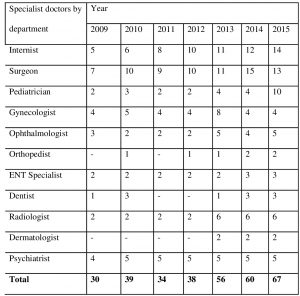

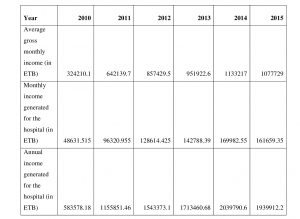

Results: A total of 37 participants were included in the study. It was found out that the number of specialist doctors in the hospital increased over the 6 years after the establishment of the private wing from 30 to 67. The quality of health services was found to improve as a result of the private wing. The annual income generated by the private wing arrangement increased from 583,578.18 ETB in 2010 to 1,939,912.2 ETB in 2015. The private wing in St. Paul hospital was successful as it contributed to the retention of specialist doctors.

Conclusions: The private wing arrangement at St Pauls Hospital Millennium Medical College has contributed to the motivation and retention specialist doctors. The arrangement generated revenue to the hospital and the quality of care was improved. Other hospitals may consider establishing private wing services.

Keywords: private wing, motivation, retention, health services

By Fitsum Girma Habte1

By Fitsum Girma Habte1

Yemisirach Abeje2

Girmaye Tamrat Bogale3(Corresponding Author)

1: Ministry of Health of Ethiopia

2: St Paul Millennium Medical College

3: Addis Ababa University, Department of Surgery

Assessment of Private Wing in Public Hospitals

The Case of St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Background

It is widely acknowledged that the health work force, as an integral part of health systems, is a critical element in achieving universal health coverage. The migration of health workers to high-income countries has been of great concern to developing countries. Developing countries have particularly suffered from high attrition rates; geographical imbalance and an uneven skill mix of health workers. As a result, achieving universal health coverage has been a big challenge for many developing countries (1). It has also been noted that globalization has an impact on hospital management, in both public hospitals and private nonprofit hospitals, in order to achieve clinical, quality and financial objectives (2).

Many African countries have started training more medical doctors to tackle the shortage of medical doctors. However, the rate of brain drain is incomparably high as compared to the rate production. Although many African countries are brain drain victims, the three severely affected ones in descending order are Ethiopia, Nigeria and Ghana. Therefore, because of the complex web of factors that influence the mobility of health workers, any efforts to scale up the health workforce in response to the shortage must be combined with effective measures to attract and maintain existing health professionals (3).

Poor remuneration is a feature of many health systems in Africa. This is especially so because most health workers in African countries work for the government and poor remuneration of civil servants helps to reduce public spending. The salaries unrealistically low and the living conditions are not up to the required standards (4). Thus, many African countries tried to improve the remuneration packages of health professionals. In Zimbabwe, for example, a retention package was implemented in for health professionals. The financial incentives were found to be less effective in retaining staff, as they were eroded by high inflation rates. Sometimes, incentives were not uniformly applied to all health workers, and did not always reach all in the target category. In Kenya, for example, the incentives mainly targeted nurses and doctors (5).

Even though the Ethiopian government has recognized the need to address the health workforce, migration of medical doctors significantly compromised the quality and access of health care services. Between 1987 and 2006, 73.2% of medical doctors left the public sector mainly due to attractive remuneration packages in other countries, international NGOs and the private sector in the country (6). Despite the rapid expansion of health training institutions and the production of physicians in Ethiopia, the gains made have been offset by brain drain (7).

To address the high attrition rates of medical doctors, the government of Ethiopia approved the establishment of private wing services in public hospitals in 1998 as part of the health sector reform. Then, implementation of the private wing arrangement in public hospitals was launched in 2008 (8). Establishing private wing in public hospitals is one of the options for private participation in hospitals recommended by the World Bank (9).

The main objective of establishing private wing in public hospitals in Ethiopia is to increase motivation and reduce attrition rates among health workers especially specialist doctors. The other objectives are to improve the quality of services; to mobilize additional resources and to subsidize the public ward; and to provide alternative care access for clients. Private wing is an official arrangement where medical services are provided, on a fee for service basis, to inpatient and outpatient clients in public hospitals. Doctors and other health workers get additional income for providing services to the private clients in public hospitals (8).

A literature review indicated that establishing well functioning private wings in public hospitals can result in retention of staff, increased client satisfaction and increased revenue flow to the hospital (10). A study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia revealed that medical professionals had the intention to continue working in government health facilities at least for three more years indicating a positive outcome of the private wing arrangement in public hospitals in retaining medical professionals (11). A study conducted in Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa, revealed that the existence of private wards in public hospitals could increase revenue flow to the hospital to improve the quality of service in public wards (12).

However, there is a significant research gap regarding the effectiveness of the private wing arrangement in Ethiopia. The effectiveness of the private wing in achieving the set objectives has not been studied comprehensively in Ethiopia to the researchers knowledge. Therefore, we assessed the effectiveness of private wing arrangement in the St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC).

Therefore, this paper was aimed to explore the effectiveness of the private wing arrangement in St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College in terms of motivating and retaining specialist doctors and improving the quality of health services.

Methods

The study was conducted in St. Paul Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from December 2015 to January 2016. Guided focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews (KIIs) were used to collect data. Relevant documents were also reviewed.

The Key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted with the Provost, Vice Provost for Medical Services, the Acting Vice Provost for Administration and Development and the Private Wing Coordinator. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with nurses, specialist doctors and anesthetists. Participants of each of the FGDs were selected from various departments that provided private wing services. Accordingly, a total of 4 key informant interviews and 4 focus group discussions were conducted. A total of 33 health professionals participated in the four FGDs.

The proposal was submitted to the institutional review board (IRB) of St. Paul hospital millennium medical college (SPHHMC) and ethical approval was obtained. Oral consent was obtained from all interviewees and participants of the FGDs. The recorded interviews were used only for the purpose of the study and were deleted at the end of the research project.

The audio-recorded interviews and FGDs were transcribed. Then content and thematic analysis was conducted. For each transcription, issues relating to the study objectives were identified and coded without predefined categories. After the completion of the coding process, themes were developed and classified. A triangulation of data sources and methods were employed, comparing information from different respondents, different methods (KIIs and FGDs) and reviewed documents.

Results

Overview of Respondents

A total of 37 health workers participated in the study. Thirteen were females while the remaining were males. Four of them participated in the key informant interviews while the remaining 33 were participants of the focus group discussions (FGDs). Out of the 33 who participated in the focus group discussions; 13 were specialist doctors, 14 were nurses and the rest 6 were anesthetists. Out of the 13 specialist doctors who participated in the FGDs, 9 of them were used to perform procedures/surgeries.

Overview of the Private Wing Services of St. Paul Hospital

The provision of private wing services was started in 2010. The major services provided in the private wing include consultation, laboratory testing, imaging services, minor and major surgeries and inpatient care. Among the 17 clinical Departments in the hospital, the following 12 departments were providing the services by January 2016.

- Surgery and Orthopedics

- Gynecology and Obstetrics

- Internal Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Laboratory

- Radiology

- Psychiatry

- Endoscopy

- Pathology

- Anesthesia

- Otorhinolaryngology

- Physiotherapy

Familiarity with the Objectives of the Private Wing

Key informants were familiar with most of the objectives of the private wing. All the key informants mentioned at least two objectives of the private wing establishment by the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) of Ethiopia. All of them were aware that motivating and retaining specialist doctors was the primary objective of private wing services.

The focus group discussants mentioned most of the objectives of the private wing establishment in the country. Motivating and retaining specialist doctors was mentioned as a primary objective of private wing in all the FGDs. A female nurse said, “Can I speak what I am feeling? The private wing service is established for the benefit of doctors. It is designed to retain and motivate doctors.” Improving access to services to clients at reasonable price; motivating and retaining other health workers; and reducing the burden on the regular medical services were mentioned by the study participants as objectives of the private wing.

Motivation and Retention of Health Workers in the Hospital

All key informants mentioned that the private wing arrangement motivated, retained and attracted specialist doctors. This was true especially for those who were performing procedures/surgeries. After the private wing establishment, the hospital managed to keep most of its specialist doctors while the number of employment applications increased. Some of the key informants mentioned that health professionals working in the radiology department and anesthetists were also motivated by the private wing arrangement.

On the other hand, key informants mentioned that the effect of the private wing arrangement in the motivation and retention of other health professionals and administrative staff was not that significant. This is because a small proportion of the revenues from the private wing services were divided among other health professionals. Especially nurses were not motivated by the arrangement as they were dissatisfied by the payment they were getting for participating in the private wing services. Most of the key informants mentioned that nurses usually complained about the ‘small’ benefits they were getting from the private wing services.

In the FGDs, specialist doctors generally agreed that the arrangement had contributed to motivation and retention of specialist doctors. They mentioned that surgeons were benefitted most from the arrangement. However, some discussants mentioned that the benefit to specialists especially those who did not perform procedures/surgeries, was not that significant.

The retention and motivation issue was also raised with specialist doctors who did not perform procedures. They agreed that the private wing did not have significant effect on the motivation and retention of specialists who did not perform procedures. The specialists mentioned that the payment is small and is subject to 35% taxation. One internist exclaimed, “The private wing service did not motivate specialist doctors as expected. It is better to work for private health institutions.”

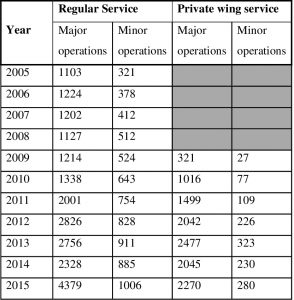

The number of specialist doctors in the hospital had steadily increased over the 6 years after the establishment of the private wing arrangement in the hospital. The number of specialist doctors increased from 30 in 2009 to 67 in 2015. (See Table 1)

Nurse FGD discussants said that specialist doctors especially surgeons were motivated and retained by the private wing arrangement. They mentioned that doctors had training and educational opportunities in addition to the financial incentives they got from the private wing. However, they mentioned that the arrangement is not motivating to other health workers especially nurses. One nurse said, “Nurses prefer to work in private clinics as they can get more money. Nurses are not motivated. There is a high turnover rate of nurses in the hospital.”

Anesthetists who were involved in the focus group discussion agreed that most health workers are benefitted from the private wing arrangement from gardener to specialist doctor. However, they mentioned that surgeons and gynecologists had more clients, performed more procedures/surgeries and hence benefitted more. They argued that though the payment is small, the private wing arrangement motivated most health workers in the hospital.

Quality of the Private Wing Medical Services

Key informants had mixed opinions on the quality of the private wing services. Some key informants said that the quality of private wing services was very good as experienced specialists provided services and clients were provided with timely medical and surgical treatment. Clients had the right to choose the specialist they wanted to get service from and this increases their satisfaction. Clients were not required to wait for a long period of time for surgical interventions. However, one key informant revealed that clients had hard time making payment for services, which affected their satisfaction. He said, “There is no separate triage/ card room for the private wing clients. The waiting area is overcrowded especially after 5:00 PM. Payment is a problem; two payment receipts are issued for the client, one for the surgeon and the other for the hospital. The location of card room and OPD is not adjacent and some departments are located far from the card room.”

Others felt that the quality of private wing medical services was not better than that of the regular medical services. The services were provided with the existing medical equipment and materials. The facilities were the same in both private and regular service, and nursing care was provided in a similar fashion. They also felt that clients expectations were not fulfilled regarding post surgery follow up. Clients expected to be followed by the surgeon who performed the surgical operation but sometimes the surgeon might delegate other surgeon or residents to follow the patients post surgery. Sometimes, follow up problems could happen even in the out patient department. Specialists provide consultation services and order various examinations. When the patient comes back on the next day with the examination result, the specialist doctor might not be available.

In the focus group discussion with specialists, most participants agreed that the quality of the private wing medical services was poor. They mentioned the following reasons for considering the quality of the services to be poor.

- The post operative follow up was poor particularly in weekends

- The private wing services were not reported while the regular services were reported in the morning sessions. There was no system for follow up and reporting of the private wing cases. Audit report was also not in place in the private wing.

- The clients did not get the required laboratory, pathology and imaging services in the hospital and hence clients were forced to visit other private health facilities where the payments for the services were expensive.

- Major surgeries were performed by fewer number of team members in the private wing while in the regular services at least three professionals were involved in each major surgery. In the regular program a surgeon and two assistants (residents) operated on a patient while in the private wing a surgeon and only one assistant (mostly nurses) operated on a client.

- Patient history was not taken and recorded properly; the specialists wrote no preoperative note or preoperative order. In the regular program the specialists write orders on patient charts to be executed by the nurses. The specialist was expected to take and document patient history that was not practical in many instances.

Some specialists mentioned that the only advantage of the private wing arrangement to the clients is that clients could get the services without waiting for a long period of time. A specialist doctor said, “If your definition of quality is presence of queue, there is no long queue in the evening but the clinical service is the same both during the day and in the evening. Nothing more, except the number of clients admitted in private wing (in the evening) may be fewer than that of the regular services (during the day time)”.

The issue of quality of the private wing medical services was also raised in the focus group discussion conducted with nurses working in the hospital. Most of the nurses perceived the quality as poor except the services provided by the radiology unit where the services were getting improved due to high tech equipment like magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) and qualified radiologists who had joined the hospital lately.

The number of beds in the private wing was limited and even if clients got bed there was no proper follow up of patients especially compared to private health facilities. Nurses were not working hard especially in the ward due to low payment. One nurse said, “If you go to private clinics the nurses ‘sneeze’ when the patient sneezes”.

The nurses mentioned that, once the patient had the operation, doctors were not coming back immediately to see how the patient was doing. The surgeons didn’t appear though the patients demanded for the visit of the specialist doctor who operated on them. They often came the following day and follow up in the weekends was particularly poor. There was no schedule for regular post-operative follow up by the specialists. Some specialists gave instructions regarding the patient through telephone. On the other hand, clients were not pre-informed or oriented about the services and they did not know what, how, where, from whom they receive the services especially after the operation. As a result, some clients were dissatisfied with the services and angry with the providers especially the nurses.

In the focus group discussion with anesthetists, most of the discussants agreed that the quality of the private wing services was good. The clients could choose the specialist doctor who provide them with the required services. The private wing bedrooms were better than that of the regular bedrooms as they were less crowded with patients. The patients got the services within a short period of time as compared to the regular services with reasonable payment. However, few anesthetists considered the private wing service quality was similar to that of the regular services.

Revenue Generation to the Hospital

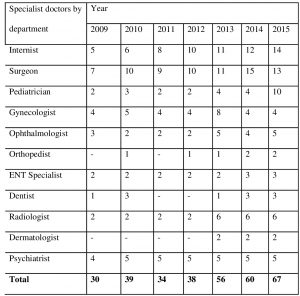

The income generated to the hospital as a result of the private wing arrangement increased from time to time. The estimated annual income generated to the hospital by the private wing significantly increased from 583,578.18 Birr in 2010 to 1,939,912.2 Birr in 2015. (See Table 2) The increment in revenue was more than three fold, which is a significant one even in the presence of high inflation rates. Key informants mentioned that 15% of the income from the private wing services had been kept as revenue generated for the hospital. Unfortunately, the hospital couldn’t fully utilize the revenue due to unclear income utilization policy by the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development of Ethiopia. However, the hospital was courageous enough to purchase reagents, equipment and 6 vehicles for department heads in the hospital. One key informant said, “We bought 6 service vehicles for department heads including the private wing coordinator. This empowers the management to assign capable department heads. That was the turning point of SPHMMC for its current improvement.”

The Effect of the Private Wing on the Regular Health Services of the Hospital

Key informants mentioned a number of positive effects of the private wing arrangement on the regular health services. Before the establishment of the private wing, it had been very difficult to find and consult specialist doctors in the evening sometimes even in the afternoon. After the private wing started, specialist doctors stayed in the hospital waiting for their private wing clients in the evening. Whenever they had to conduct procedures or see patients at the OPD (out patient department), then they would stay in the hospital even at night. This facilitated better care for emergency patients in the regular service at any time including the weekends. Another positive effect mentioned was that the load on the regular services had been reduced. As many patients were getting treatment in the private wing with reasonable cost, the number of those patients waiting for treatment in the regular service decreased. One respondent related, “Before the private wing service establishment, patients had to wait for three years to get operated. Currently the waiting time has been reduced to three months.”

Most key informants mentioned that efficiency of the hospital had been increased as a result of the private wing establishment. Given the existing facilities more patients were served. One key informant said, “Before the private wing establishment, some surgeries were cancelled due to various reasons. After the private wing establishment the number of patients operated per physician increased.” One of the key informants reported that before the private wing establishment gynecology department used to serve 400 clients per month while after the establishment around 1000 clients were served per month. This contributed to better image and perception of the hospital by the public.

Another positive outcome of the private wing mentioned by key informants is that the hospital is able to retain its specialist doctors. One of the key informants said, “As a management team member, I am happy to see health workers are motivated, committed and ready to change.” The hospital is even attracting specialists from other hospitals. In turn this improved the access and quality of various types of health services in the hospital. Even residents are benefiting from the private wing arrangement. They assist in various procedures in the private wing in addition to those conducted in the regular services. Accordingly, residents had got more exposure to various types of procedures and they would be more competent. That means the private wing improved the learning teaching process of the hospital medical college.

On the other hand, the key informants revealed that the private wing establishment also had negative effect on the regular health service provision. Bedrooms were taken from regular service that could affect service provision in the regular ward. There had been conflicts of interest among health workers that brought additional burden to the hospital managers. Complaints were continuously reported as a result of staff dissatisfaction on the private wing arrangement.

One of the key informants noted that health professionals were more motivated and creative in the private wing than the regular services. Knowingly or unknowingly those health providers who benefited from the private wing service showed the tendency to push patients to the private wing service by extending the waiting list of clients for operation in the regular program. He explained, “In some cases, clients are forced to wait for three weeks to get operated in the regular program, but in the private wing service they can get operated within three days for the same health problem. Hence, sometimes clients are forced to use the private wing service though it may not be their preference.”

Focus group discussants were asked on the effect of the private wing on the regular health services of the hospital. Participants discussed on the positive and negative effects of the private wing. It was found out that the specialist doctors, nurses and anesthetists participated in the FGDs had similar feelings regarding the effect of the private wing on the regular medical services of the hospital.

Most participants agreed that the private wing resulted in decreased workload at the out patient department (OPD) as well as in the in patient wards of the regular service. According to the health professionals participated in the FGDs, the regular hospital services were upgraded and efficiency increased as a result of the private wing establishment. They mentioned that the private wing arrangement improved the availability of specialist doctors in the evenings, weekends & holydays. This improved the quality of medical care provided as part of the regular hospital services. They also mentioned that the waiting list of clients in the regular service decreased after the private wing service started.

The FGD discussants observed that there were some problems as a result of the private wing establishment, which negatively affected the regular hospital services. They observed a tendency to prioritize the private wing services than the regular services by health care providers. As a result, working time of the regular services was compromised for the private wing services. According to the Private Wing Guideline, the private wing services should be provided outside of the working hours. This means, in the working days, the private wing services should be started after 5:00 pm. However, FGD participants mentioned that services were started before 5:00 pm even before 4:00 pm.

Some specialist doctors delegate residents to follow up regular time clients. This resulted in decreased quality of regular medical services. One nurse stated that, “Specialist doctors are not available on time at the OPD for the regular services. They don’t see many patients. In addition to providing services in the private wing, they have classroom sessions with their students and research activities. And therefore, they delegate residents to provide follow up services. Sometimes, patients are told to comeback another time, as resident doctors do not make major decisions without the consultation of the specialist.”

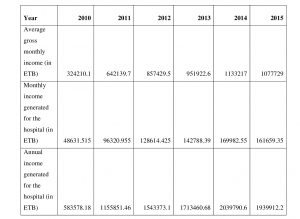

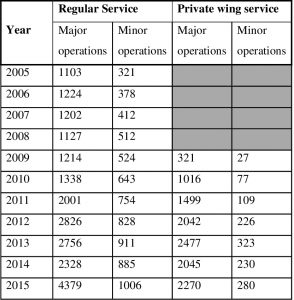

In order to assess the effect of the private wing on the regular medical services, documents were also reviewed. The number of surgeries conducted each year before the establishment of the private wing was compared with the number of surgeries conducted each year after the establishment of the private wing in 2001 E.C. It was found out that the number of both major and minor surgeries conducted in the regular service increased every year especially after the establishment of the private wing. The number of major surgeries conducted in the regular service of the hospital increased from 1214 in 2001 at the establishment of the private wing to 4379 in 2007. The number of minor operations in the regular program increased from 524 in 2001 to 1006 in 2007. In the same period of time the number of surgeons increased from 7 to 13 (See Table 3).

Discussion

All key informants mentioned that the private wing arrangement motivated, retained and attracted specialist doctors. This was true especially for those who were performing procedures/surgeries. After the private wing establishment, the hospital managed to keep most of its specialist doctors while the number of employment applications increased. Most focus group discussants agreed with the key informants in that the arrangement motivated and retained specialist doctors who were performing procedures. This was objectively verified as the number of specialist doctors in the hospital had steadily increased over the 6 years after the establishment of the private wing arrangement as per the document review finding. Though we cannot say for sure that the increment in the number of specialist doctors is solely due to the existence of the private wing, we can recognize that the private wing has contributed to the retention of specialist doctors in the hospital. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia which revealed that medical professionals had the intention to continue working in government health facilities at least for three more years as a result of the private wing arrangement in the public hospitals they practice (11). A study conducted in Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa, revealed that the existence of private wards in public hospitals could increase revenue flow to the hospital to improve the quality of service in public wards (12).

The income generated to the hospital as a result of the private wing arrangement increased from time to time. The estimated annual income generated to the hospital by the private wing significantly increased from 583,578.18 ETB in 2010 to 1,939,912.2 ETB in 2015. The increment in revenue was more than three fold, which is very significant even in the presence of high inflation rates. A similar finding was reported in a study conducted in Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa, which revealed the existence of private wards in public hospitals, could increase revenue flow to the hospital (12).

The private wing was found to have a number of positive and some negative effects in the regular health services of the hospital. After the establishment of the private wing, specialist doctors were available all the time even at night and weekends for consultation. Patient who could afford were getting treatment in the private wing reducing the workload of the regular program to some extent. Respondents felt that as a result of retention of experienced specialists, the quality of the regular medical services was maintained. All these factors could sum up to significantly improve the quality of medical services provided in the hospital.

Interestingly, the number of both major and minor surgeries conducted in the regular service increased every year after the establishment of the private wing. The rate of increment in the number of both major and minor surgeries is more than that of the rate of increase in the number of surgeons. It seems like the private wing establishment resulted in increased number of surgeries conducted in the regular program. Most notably, in 2015, the number of major surgeries conducted was almost twice that of 2014. This is in conformity that the hospital claimed that it used the private wing arrangement to motivate the surgeons to perform more in the regular program.

On the other hand, bedrooms were taken from regular service that could affect service provision in the regular ward. There had been conflicts of interest among health workers that brought additional burden to the hospital management. A tendency to give more emphasis to the private wing services than the regular services was observed and as a result working time of the regular services was compromised for the private wing services.

Conclusions

The private wing arrangement had significantly contributed to the motivation and retention specialist doctors especially those who used to perform procedures most notably the surgeons. Other health workers like anesthetists and pharmacists were also benefited from the private wing. However, it seems like nurses were dissatisfied by the payment they were receiving for providing private wing services.

Significant amount of revenue had been generated to the hospital as a result of the private wing establishment. The amount of revenue generated had been increasing every year since the establishment of the private wing in the hospital.

The private wing establishment was found to have a number of positive and some negative effects in the regular health services of the hospital. After the establishment of the private wing, specialist doctors were available all the time even at night and weekends for consultation, which improved the quality of services. On the other hand, bedrooms were taken from regular service that could affect service provision in the regular ward.

Therefore, it is recommended that St. Paul Hospital,

- Continue providing the private wing services to retain and motivate specialist doctors and improve the quality of services in the hospital.

- Dedicate a separate building/ ward including consultation rooms, inpatient wards, pharmacy and the card section for the private wing services to mitigate the unfavorable effect of the private wing on the regular services.

- The nurses complained a lot about the amount of payment they were receiving. Though it is difficult to satisfy everyone, the payment distribution should be fair. Therefore, the hospital may consider reviewing the payment distribution for fairness and acceptability and make the necessary measures as needed.

Other public hospitals may learn from the experience of St. Paul hospital and consider establishing the private wing services to motivate and retain their doctors and other health professionals.

Abbreviations

ETB: Ethiopian Birr (unit of currency in Ethiopia)

FGD: Focus Group Discussion

FMOH: Federal Ministry of Health

HCF: Health Care Financing

HR: Human Resources

MPH: Master of Public Health

OPD: Out Patient Department

SPHMMC: St.Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the health professionals and key informants who participated in the study. We would also like to thank the data collectors for conducting the key informant interviews and facilitating the focus group discussions. Finally, we would like to thank St. Paul Hospital Millennium Medical College for covering the costs of data collection of the study.

Author Contributions

Fitsum Girma and Girmaye Tamrat substantially contributed to the design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; and approval of the submitted version. Yemisrach Abeje did part of literature review. Fitsum Girma wrote the final report and Girmaye Tamrat revised it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Each author agrees to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The study was funded by St Pauls Hospital Millennium Medical College. The money was used for stationery and data collection.

References

- World Health Organization (2013). World Health Report 2013: Universal Health Coverage, 1-9.

- Patrick Mordelet(2009). The impact of globalisation on hospital management: Corporate governance rules in both public and private nonprofit hospitals, Journal of Management & Marketing in Healthcare, 2:1, 7-14, DOI: 1179/mmh.2009.2.1.7.

- Lehmann U, Dieleman M, Martineau T (2008). Staffing remote rural areas in middle- and low-income countries: a literature review of attraction and retention. BMC Health Services Research, 8 (19), 1-10.

- Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA. (2004). Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. The Lancet, 364: 900–906.

- Mathauer, I. and I. Imhoff (2006). Health worker motivation in Africa: The role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Human Resources for Health, 4 (1), 24–41.

- Berhan, Y. (2008). “Medical Doctors’ profile in Ethiopia: production, attrition and retention”. Ethiopian Medical Journal, 46(01): 1-7.

- Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia (2010). Health Care Reform Manual, Final Draft, 2-4.

- Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. (2014). The National guideline on the establishment of private wing in public Hospitals, 1-10.

- The World Bank Group, Private Sector and Infrastructure Network (2002). Public Hospitals: Options for Reform through Public-Private Partnerships. Public Policy for the Private Sector, Note number 241.

- Management Sciences for Health, USAID Rwanda Health System Strengthening Project. (2016). Private Sector Brief. August 2016, no. 4.

- Bogale, B. (2015). The Role of Private Wing set up in Public Hospitals in Reducing Medical Professionals’ Turnover. Journal for Studies in Management and Planning, 11(01): 13-18.

- Wadee H. Gilson L (2007). Private Wards in public hospitals: what are the policy and governance implications? A case study of Tygerberg Academic Hospital. Centre for Health Policy, University of Witwatersand, Johannesburg, November 2007; 29-40.

List of Tables

Table 1: Total number of specialist doctors in the six years after the establishment of private wing services in SPHMMC, January 2016.

Table 2: Annual Revenues Generated from the Private Wing Services in St. Paul Hospital, January 2016

Table 3: Average number of surgeries (minor and major) per year before and after private wing service establishment (2001 E.C) in St. Paul Hospital, January 2016