Collective activism to overturn philanthrocapitalism’s hold on global health is an urgent necessity. This effort should draw from, and build upon, the resistance to the UN’s promotion of “multi-stakeholder partnerships” and neoliberal global restructuring since the 1990s. Those actors who have contributed either unwittingly, or through silent assent, or even with active collaboration, to the global health plutocracy also share responsibility in re-democratizing it

Advance preview of Chapter 10 from Health Care under the Knife: Moving Beyond Capitalism for Our Health, Howard Waitzkin and the Working Group for Health Beyond Capitalism, eds. Monthly Review Press (forthcoming 2018). Published under licence from the authors

U.S. Philanthrocapitalism and the Global Health Agenda: The Rockefeller and Gates Foundations, Past and Present

By Anne-Emanuelle Birn

Professor of Critical Development Studies, University of Toronto, Canada. ae.birn@utoronto.ca

and Judith Richter

Affiliated Senior Researcher, Institute of Biomedical Ethics and History of Medicine, University of Zurich, Switzerland

A fiercely competitive and enormously successful U.S. businessman turns his attention mid-career to worldwide public health. Historic curiosity? Or the most powerful contemporary actor in this field? As it turns out, both. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) began to use John D. Rockefeller’s colossal oil profits to stake a preeminent role in international health (as well as medicine, education, social sciences, agriculture, and natural sciences). About a century later, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), named for the software magnate and his wife, had become the most influential agenda-setter in the global health and nutrition arena (and in agriculture, development, and education).

Each of these powerhouse foundations emerged at a decisive juncture in the history of international health. Each foundation was started by the richest, most driven capitalist of his day. Each businessman faced public condemnation for his unscrupulous, monopolistic business practices.1 Both have been subject to adulation and skepticism regarding their philanthropic motives.2 Sharing narrow, medicalized understandings of disease and its control, the RF sought to establish health cooperation as a legitimate sphere for intergovernmental action and shaped the principles, practices, and key institutions of the international health field,3 while the BMGF appeared as global health governance was facing a crisis.

Both foundations and their founders were/are deeply political beings, recognizing the importance of public health to capitalism and of philanthropy to their reputations, while claiming the purportedly neutral technical and scientific basis of their efforts.

However, there is one critical difference between them: the RF supported public health as a public responsibility, while BMGF actions have challenged the leadership and purview of public, intergovernmental agencies, fragmenting health coordination and allotting a massive global role for corporate and philanthropic “partners.”4

Given the confluence of largesse and agenda setting at distinct historical moments, several questions emerge: How and why have U.S. mega-philanthropies played such an important role in producing and shaping knowledge, organizations, and strategies to address health issues worldwide? What are the implications for global health and its governance?

Such questions are particularly salient given that “philanthrocapitalism” is hailed as the means to “save the world” even as it depends on profits amassed from financial speculation, tax shelters, monopolistic pricing, exploitation of workers and subsistence agriculturalists, and destruction of natural resources—profits that are channeled, albeit indirectly, into yet more profiteering. The term philanthrocapitalism, coined by The Economist’s U.S. business editor, refers both to infusing philanthropy with the principles and practices of for-profit enterprise and to demonstrating capitalism’s benevolent potential through innovations that allegedly “benefit everyone, sooner or later, through new products, higher quality and lower prices.”5

Most government entities are subject to public scrutiny, but private philanthropies are accountable only to their own self-selected boards. Just a few executives make major decisions that affect millions of people. In North America (and various other jurisdictions), corporate and individual contributions to non-profit entities are tax deductible, removing an estimated $40 billion from U.S. public coffers each year.6 At least one-third (depending on the tax rate) of private philanthropies’ endowments thereby is subsidized by the tax-paying public, which has no say in how such organizations’ priorities are set or monies spent.

This chapter compares and contrasts the goals, modus operandi, and agenda setting roles of the RF and BMGF. We proposed that both the early twentieth century RF and the contemporary BMGF have significantly shaped the institutions, ideologies, and practices of the international/global health field, sharing a belief in narrow, technology-centered, disease-control approaches. The RF, however, favored creation of a singular, public, coordinating agency for global health (eventually, the World Health Organization, WHO), while the BMGF’s privatizing approaches undermine WHO’s constitutional mandate to promote health as a fundamental human right. Indeed, the BMGF’s venture-philanthropy approach—applying methods from the venture capital field to charitable giving7—underpins and is emblematic of the business models that now penetrate the global public health field. These conditions have resulted in extensive private, for-profit influence over global health activities and have blurred boundaries between public and private spheres, representing a grave threat to democratic global health governance and scientific independence.8

Rockefeller International Health in an Age of Imperialism

In 1913, as “tropical” health problems plagued imperial interests, oil mogul-cum- philanthropist John D. Rockefeller established the RF with the professed goal of “promot[ing] the well-being of mankind throughout the world.” His efforts were part of a new American movement: “scientific philanthropy.” In his 1889 manifesto, The Gospel of Wealth,9 Scottish-born, rags-to-riches steel magnate Andrew Carnegie had called on the wealthy to channel their fortunes to the societal good by supporting organized social investments rather than haphazard forms of charity.

Rockefeller followed this gospel by donating to the nascent field of public health, burnishing his social benefactor image in the process. His advisors advocated starting by tackling anemia-provoking hookworm disease: it was easily diagnosed and treated with medication and was viewed as central to the economic “backwardness” of the U.S. South, impeding industrialization and economic growth. That hookworm was not a leading cause of death, or that treatment occasionally provoked fatalities, seemed immaterial.

The handsomely-funded Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease (1910–1914) showered eleven southern states with teams of physicians, sanitary inspectors, and laboratory technicians who administered deworming medication; promoted shoe wearing and latrine use; and disseminated public health materials, working through churches and agricultural clubs. (These activities brought favorable attention to the Foundation until a [false] rumor spread that the campaign aimed to sell shoes, prompting the Rockefeller name to fade into the background).10 Even if did not “eradicate” the disease, the hookworm campaign ignited popular interest in public health, and the RF swiftly created an International Health Board to expand the work.

The RF’s public health activities also served to counter negative publicity about the Rockefeller oil monopoly. Bad press mounted in 1914 when some two dozen striking miners and their families were killed at the Ludlow, Colorado, mine, owned by a Rockefeller-controlled coal producer. Workers, investigative journalists, and the general public readily linked Rockefeller business and philanthropic interests, regarding “robber barons’” donations as attempts to counter working class unrest, political radicalism, and other threats to big business.11

The Rockefeller family was thus advised to engage in philanthropic spheres such as health, medicine, and education, perceived as neutral and unobjectionable. Over the next four decades, the RF dominated international health. Its staff, steered by active trustees and managers (initially overlapping with Rockefeller business advisors), oversaw a global enterprise of health cooperation through regional offices in Paris, New Delhi, Cali, and Mexico City. Hundreds of RF officers led its country-based public health work in scores of countries around the world.12 By the time the International Health Division (as the International Health Board was renamed in 1927) was disbanded in 1951, it had spent the equivalent of billions of dollars on major tropical disease campaigns against hookworm, yellow fever, and malaria, plus smaller programs combatting yaws, rabies, influenza, schistosomiasis, and malnutrition, in almost 100 countries and colonies. The Division also marshaled national commitment to its campaigns by obliging government co-financing, typically starting at 20 percent of costs and rising to the full amount within a few years. It also founded 25 schools of public health across the world and provided fellowships to 2,500 public health professionals to pursue graduate study, mostly in the United States.13

But the RF rarely addressed the most important causes of death, notably infantile diarrhea and tuberculosis, for which technical fixes were not then available and which demanded long-term, socially oriented investments, such as improved housing, clean water, and sanitation systems. The RF avoided disease campaigns that might be costly, complex, or time-consuming (other than yellow fever, which imperiled commerce). Most campaigns were narrowly construed so that quantifiable targets (insecticide spraying or medication distribution, for example) could be set, met, and counted as successes, then presented in business-style quarterly reports. In the process, RF public health efforts stimulated economic productivity, expanded consumer markets, and prepared vast regions for foreign investment and incorporation into the expanding system of global capitalism.

Alongside its disease campaigns, the RF sustained the international health field’s evolving institutional framework. The League of Nations Health Organisation (LNHO), founded after World War I, was modeled partially on the RF’s International Health Board and shared many of its values, experts, and know-how in disease control, institution building, education, and research, even though the LNHO strived to challenge narrow, medicalized understandings of health. Instead of being supplanted by the LNHO, the RF became its major patron and lifeline.14 Addressing the socio-political conditions underlying ill health was an important political rationale for public health in the 1930s’ climate of anti-fascist, labor, and socialist activism. The RF drew on, listened to, and even bankrolled certain progressive political perspectives, including those of avowed left-wing scientific researchers and public health experts,15 although such support was always subordinate to its technical model and to bolstering U.S. capitalist power.

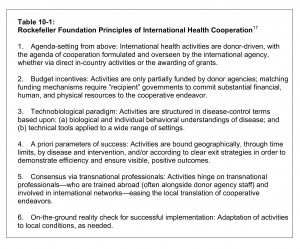

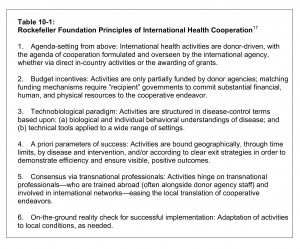

Yet the RF identified its most significant international contribution as “aid to official public health organizations in the development of administrative measures suited to local customs, needs, traditions, and conditions.”16 Thus, its self-defined, broader gauge of success was its role in generating political and popular support for public health, creating national public health departments, and furthering the institutionalization of international health (Table 10-1).

Philanthropic status conferred independence from public oversight; the RF was accountable only to its board. Its influence over agenda setting and institution building was enabled by its presence at the international level, bolstered by behind-the-scenes involvement in virtually every kind of public health activity and by missionary zeal in setting priorities. Yet, responding dynamically to shifting political, scientific, economic, cultural, and professional terrains, the RF’s activities also involved extensive give and take, marked by moments of negotiation, cooptation, imposition, rejection, and productive cooperation. Uniquely for the era, it operated not only as a funding agency but simultaneously as a national, bilateral, multilateral, international, and transnational agency.18

The Cold War Interlude and the Rise of Neoliberalism

After WHO was established in 1948, the RF drew back from its leading role in international health, leaving a powerful but problematic legacy: it had generated political and popular support worldwide for public health and championed the institutionalization of international health, but it also entrenched outside agenda setting and a technobiological approach. WHO inherited the RF’s personnel, fellows, ideologies, practices, activities, and equipment, pursuing high profile, vertical eradication campaigns against malaria, smallpox, and other diseases.19

During the Cold War, WHO was joined on the international health stage by bilateral agencies, international financial institutions, and other United Nations (UN) agencies, plus a dizzying array of humanitarian and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The U.S. and Soviet blocs both employed health infrastructure in their political and ideological rivalry, building hospitals, clinics, and pharmaceutical plants, sponsoring thousands of fellowships, and participating in RF-style disease campaigns.

In the 1970s, WHO’s vertical approach began to be challenged. Its member states, especially newly decolonized countries not aligned with either the Soviet Union or the United States, sought to address health socio-politically. Halfdan Mahler, WHO Director-General from 1973 until 1988, provided the visionary leadership in this reorientation. The primary health care movement, enshrined in the seminal 1978 WHO- UNICEF Conference and Declaration of Alma-Ata and WHO’s accompanying “Health for All” policy, called for health to be addressed as a fundamental human right through integrated social and public health measures that recognized the economic, political, social, and cultural contexts of health and focused on prevention rather than cure.20 Health for All was also part of a larger UN effort, the New International Economic Order (NIEO), which also called on UN agencies to help regulate transnational corporations via binding international codes.

Just as WHO was trying to escape the RF’s legacy of narrow health interventions, however, it became mired in political and financial crises. The economic situation in the late 1970s and early 1980s prevented many member countries from paying WHO dues. Meanwhile, U.S. resistance to what it portrayed as illegitimate “supra-national regulation,” amid the overall rise of neoliberal political ideology dampened support for publicly funded international health institutions. These conditions also contributed to a budget freeze in terms of dues paid by member states, which still remains in place. Moreover, U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s administration unilaterally cut its assessed contributions to the UN by 80 percent in 1985 and then withheld its WHO member dues in 1986 to protest WHO’s regulation of health-related commercial goods and practices,21 particularly pharmaceuticals and infant foods.22 By the early 1990s, less than half of WHO’s budget came from member country dues, while many donors, now including a variety of private entities, stipulated the programs and particular activities to which they assigned funds. Today almost 80 percent of WHO’s budget comes from donors who determine how their contributions are to be spent.

After the Cold War, international health efforts were justified on the grounds of promoting trade, disease surveillance, and health security.23 By this time, WHO was being sidelined by the World Bank, armed with a far larger health budget and a drive to privatize health systems as well as water and other essential public services, and by an emerging paradigm forging UN “partnerships” with corporate actors. Many bilateral agencies, plus certain UN agencies such as UNICEF, bypassed WHO altogether.24 With reduced intergovernmental spending, what was now dubbed “global health” philanthropy returned, its re-emergence coinciding and intertwined with the rise of neoliberalism.

Enter the Gates Foundation

By 2000, overall global health spending had become stagnant. Negative views of overseas development assistance were encouraged by political and economic elites and corporatized mass media. Many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were floundering under the multiple burdens of HIV/AIDS, re-emerging infectious diseases, and burgeoning chronic diseases, all compounded by decades of World Bank and IMF- imposed cuts in social expenditures and the negative effects of trade and investment liberalization. Into this void a self-proclaimed savior for global health appeared, quickly molding its agenda within just a few years.

The BMGF was established in 2000 by Microsoft founder and long-serving CEO Bill Gates, the world’s wealthiest person, and his wife Melinda.25 As with Rockefeller, Gates’s philanthropic entry coincided with bad press. He launched the Children’s Vaccine Program, a BMGF precursor, in 1998,26 when Microsoft was attracting negative publicity for lobbying to cut the U.S. Justice Department’s budget precisely when the company was mired in a federal antitrust suit.27 In 1999, Gates gave a $750,000 founding donation to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (now “GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance”), an initiative announced at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Later that year Microsoft faced a class-action lawsuit for abusing its software monopoly from millions of California consumers. BMGF-funded initiatives rapidly proliferated, even as Microsoft was facing further anti-competitive charges in the European Union. In 2002 the BMGF co-founded the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and became a major funder of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (now called the Global Fund).

Today the BMGF, co-chaired by the couple together with Bill Gates Senior, is by far the largest philanthropic organization involved in global health and the largest charitable foundation in the world. The BMGF spends more money on global health than any government except the United States.28 Its 2015 endowment was $39.6 billion, including $17 billion donated by U.S. mega-investor Warren Buffett, the BMGF’s sole trustee.29

Through 2015, the BMGF had granted $36.7 billion in total; recent annual spending is around $6 billion. Approximately $1.2 billion goes into “global health” (including HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis) and $2.1 billion into “global development” (including polio, vaccine delivery, maternal and child health, family planning, and agricultural development). The BMGF’s budget for global health-related activities has surpassed that of WHO in some recent years. Since 2008, the BMGF has been the largest private donor to WHO (much of this funding is earmarked for polio eradication).

The BMGF’s stated global health aim is “harnessing advances in science and technology to reduce health inequities,”30 encompassing both treatment (via diagnostic tools and drug development) and preventive technologies (such as vaccines and microbicides). Initially, the Seattle-based Foundation focused on a few disease-control programs, mostly as a grant-making agency. Now its efforts reach over 100 countries. It maintains offices in Africa, China, India, and the United Kingdom, with more than 1,400 staff members.

Echoing RF practices, the BMGF requires co-financing from its governmental “partners,” designs technologically oriented programs to achieve positive results from narrowly defined goals, and emphasizes short-term achievements. The BMGF has developed an extraordinary capacity to marshal other donors to its efforts, including bilateral agencies, which collectively contribute ten times more resources to global health each year than the BMGF but with considerably less recognition.31 The BMGF has been widely lauded for infusing cash and life into the global health field and encouraging other participants.32 But even some of its supporters decry its lack of accountability and transparency (over what are, after all, taxpayer-subsidized dollars) and its undue power in setting the global health agenda.33

The BMGF Approach and Its Dangers

As a key funder of global health initiatives, the BMGF collaborates with a range of public, private, and intergovernmental agencies, as well as universities, corporations, advocacy groups, and NGOs. Like the RF, the BMGF sends the vast majority of its monies for global health to or through entities in high-income countries. Through 2016, three quarters of the total funds granted by its Global Health Program went to sixty organizations, 90 percent of which are located in the United States, United Kingdom, or Switzerland.34

A major focus of BMGF global health funding is vaccine distribution and development. In 2010 it committed $10 billion over ten years to vaccine research, development, and delivery. While vaccines are important and effective public health tools, historical evidence demonstrates that mortality declines in high income as well as some LMICs since the nineteenth century have been mostly due to improved living and working conditions (including access to clean water, sanitation, and primary health care) in the context of social and political struggles.35

The BMGF’s reductionist approach emerged clearly in Bill Gates’s keynote address in May 2005 to the fifty-eighth World Health Assembly, the annual gathering at which WHO member states set policy and decide on key matters. Gates invoked smallpox eradication through vaccination, whose cost was low due to its non-patented status, to chart a global health agenda: “Some… say that we can only improve health when we eliminate poverty. And eliminating poverty is an important goal. But the world didn’t have to eliminate poverty in order to eliminate smallpox – and we don’t have to eliminate poverty before we reduce malaria. We do need to produce and deliver a vaccine.”36 Gates’s deceptively simple technological solution to the complex problem of malaria implies that approaches based on social justice can simply be ignored.

Similarly, the BMGF’s Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative funds scientists in nearly 40 countries to carry out “bold,” “unorthodox” research projects as long as they largely disregard the underlying social, political, and economic causes of ill health, including unprecedented accumulation of wealth.37

To be sure, the BMGF has also supported other kinds of initiatives, albeit at a smaller scale. In 2006, it gave a $20 million startup grant to the International Association of National Public Health Institutes and a $5 million grant to the WHO-based Global Health Workforce Alliance, which sought to address the shortage of health personnel in LMICs. BMGF funding has often had a privatizing impetus. Recently, the BMGF has begun funding “universal health coverage” (not the same as access to publicly-funded universal health care),38 for example via a $2.2 million grant to the Results for Development Institute, which works to “remov[e] barriers impeding efficiency in global markets (for instance in health).”39

Despite the shortcomings of a technology-focused, disease-by-disease approach to public health problems, this model now prevails, shepherded by the BMGF’s role in formal global health decision-making bodies. Its role mounted in 2007 with the formation of the “H8”—WHO, UNICEF, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), UNAIDS, the World Bank, the BMGF, GAVI, and the Global Fund. Most are involved with and/or heavily influenced by the BMGF. The H8, akin to the former G8 (composed of 8 powerful nations collaborating on economic policies and “security” issues: United States, Japan, Germany, France, United Kingdom, Canada, Italy, and Russia; now G7 without Russia) holds meetings behind closed doors to shape the global health agenda.40

Like the RF at its height, the BMGF’s sway over the global health agenda stems from the magnitude of its donations, its ability to mobilize resources quickly and allocate substantial sums to large initiatives, the high profile of its patron, and the leverage it garners from the extraordinary range of organizations with which it partners. Yet Bill Gates’s response to the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak in West Africa raises yet more questions about his vision. He called for a supranational, militarized global health authority, modeled on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, to be mobilized in the event of future epidemics, usurping WHO’s coordinating mandate while undercutting national sovereignty and democratic rule.41

The BMGF and Conflicts of Interests

Conflicts of interest in financing and staffing pervade the BMGF. In recent years it has been critiqued for investing its endowment in polluting and unhealthy food and beverage industries and in private corporations that benefit from its support for particular global health and agriculture initiatives.42 Although the BMGF sold many of its pharmaceutical holdings in 2009,43 its financial interests in Big Pharma remain through Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway holdings (almost half of the BMGF’s endowment investments).

Overly close relationships between the BMGF and Big Pharma put into question the Foundation’s stated aim of reducing health inequities, given that profiteering by these corporations impedes access to affordable medicines.44 In addition, various senior BMGF executives used to work at pharmaceutical companies.45 For instance, Dr. Trevor Mundel, president of the BMGF’s Global Health Program, was previously a senior executive at Novartis; and his predecessor, Dr. Tachi Yamada, was an executive and board member of GlaxoSmithKline. Yet such “revolving door” problems are rarely discussed publicly.46

Advocates for affordable life-saving medicines have also raised questions about the BMGF’s stance on intellectual property (IP). Gates admits that his Foundation “derives revenues from patenting of pharmaceuticals.”47 Microsoft has long been an ardent supporter of IP rights – which facilitate its worldwide capture of markets48 – and has taken a leading role in assuring passage of the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).49 The BMGF and Microsoft are legally separate entities (as the RF and Rockefeller companies were), but linkages, such as BMGF’s hiring of a Microsoft patent attorney in 2011 for its Global Health Program,50 are troubling. The government of India became so concerned about the BMGF’s pharmaceutical ties and related conflicts of interest that, in early 2017, it cut off all financial ties between the national advisory body on immunization and the BMGF.51

Such conflicts of interest also manifest themselves at WHO, due to the increasing role of the BMGF as the main financier for WHO’s budget. The problem of WHO’s dependence on “voluntary” funding – its most fundamental institutional conflict of interest – remains unaddressed despite concerted efforts by civil society organizations.52 It would take just $2.2 billion – which is only half that of New York- Presbyterian Hospital’s budget,53 – to fully fund WHO through Member State dues.

Instead of lifting the freeze on WHO member state dues, WHO’s most recent reform produced the 2016 Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors.54 This further legitimized BMGF and corporate influence on WHO by specifically allowing philanthropic and corporate actors to apply for “Official Relations” status, which was originally meant for NGOs that shared the specific goals articulated in WHO’s constitution.

The BMGF, Public-Private Partnerships, and Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives

Among the key levers through which the BMGF has garnered influence over agenda setting and decision making are “public-private partnerships” (PPPs). The generic term PPP covers a multitude of arrangements, activities, and relationships. In the early 1990s, PPPs were promoted as a way of funding and implementing global health initiatives in line with neoliberal prescriptions for privatizing public goods and services. By the late 1990s, UN agencies had classified a wide range of public-private interactions as “partnerships” or “multi-stakeholder initiatives” (MSIs). Both concepts lump all participants together, erasing key differences in the roles and objectives of those striving for human rights to health and nutrition, and those ultimately pursuing their bottom line.55 Many of the major global health PPPs now in existence, with budgets ranging from a few million to billions of dollars – such as GAVI, Stop TB, Roll Back Malaria, and GAIN – were launched by the BMGF or have received funding from it.

These public-private hybrids encourage a close relationship between a public institution and business rather than an arms-length one and promote a shared process of decision making among supposedly equal partners or “stakeholders.” Such arrangements have enabled business interests to obtain an unprecedented role in global health policy making with inadequate public scrutiny or accountability56 and are markedly different from the RF’s advocacy of public health as the responsibility of the public sector to which public health activities should be accountable.

The BMGF’s prominent role in the two most powerful PPPs – GAVI and the Global Fund, both H8 members – and its founding of GAIN underscore the primacy of the foundation in shaping and enhancing the clout and business venture orientation of PPPs. GAVI has been the model for almost all global health PPPs. When Bill Gates first funded it, he was following the venture philanthropy model created in the mid-1990s by dot.com billionaires who advocated bringing business thinking and jargon into the public arena. The arrangements are characterized by the active involvement of the donor entrepreneurs and foundation staff in the recipient organizations and by board representation from the for-profit sector,57 with corporate presence creating an intimidating environment for some government representatives.58

GAVI has been critiqued for emphasizing new vaccines instead of ensuring that existing effective vaccination against childhood diseases is universally carried out. It has been characterized as a “top-down” arrangement emphasizing technical solutions that pay scant attention to local needs and conditions59 and underwrite already hugely profitable pharmaceutical corporations in the name of “saving children’s lives.”60 Indeed, GAVI has subsidized companies, such as Merck, for already profitable products such as pneumococcal vaccine, while countries eligible for GAVI support are expected over time to take on an increasing proportion of costs, eventually losing both direct subsidies and access to lower negotiated vaccine prices.61

Similar issues surround the Global Fund, the largest global health PPP in dollar terms; it received a $100 million startup grant from the BMGF, which has since given it almost $1.6 billion. Sidelining UN agencies, the Global Fund had disbursed $33 billion to fund programs in 140 countries as of early 2017, in the process further debilitating WHO and any semblance of democratic global health governance. WHO and UNAIDS have no voting rights on the board, but the private sector, currently represented by Merck and the BMGF, does. The Global Fund, like many PPPs, is known to offer “business opportunities” – lucrative contracts and influence over decision making – as a prime feature of its work.

Similarly, since the BMGF and UNICEF founded GAIN, this PPP has popularized the term “micronutrient malnutrition” to justify its prime focus on food fortification and supplementation. GAIN argues that “in an ideal world we would all have access to a wide variety of nutrient rich foods which provide all the vitamins and minerals we need. Unfortunately, for many people, especially in poorer countries, this is often not feasible or affordable.”62 This reasoning ignores food supply and distribution problems. Severe malnutrition prevails in regions with extremely fertile soil and advantageous growing conditions, producing some of the world’s most nutritious crops, but these are largely for export markets, leaving local people on low incomes priced out of access to nutritious food.63

Overall, the PPP- and MSI-peppered global health architecture fragments and destabilizes the global health landscape, undermining WHO’s authority and capacity to function and coordinate.64 These arrangements allow private interests to frame the public health agenda, provide legitimacy to corporations’ involvement in the public domain, conflate corporate and public objectives, and raise multiple conflicts of interest, with most PPPs channeling public money into the private sector, not the other way around.65 Most recently, a new global health campus built to house the headquarters of major PPPs, just a stone’s throw from WHO, will further shift the node of global health governance physically and metaphorically away from UN agencies.66

Other Avenues of Influence

Relatively unexamined is the $3.5 billion in grants from the BMGF in recent years for “policy and advocacy” work. These grants fund extensive health and development media coverage, including of BMGF-supported programs, in outlets spanning the U.S. Public Broadcasting System to the United Kingdom’s Guardian newspaper.67 This coverage adds to the considerable self-publicity generated by Bill and Melinda Gates themselves, who have been featured in countless profiles over the years. Their 2017 annual letter, for example, used cherry-picked evidence to promote an overly positive and misleading spin on the BMGF’s achievements.68 By contrast, the RF historically underplayed its public profile, largely because it was faced with a more vigilant media and a public skeptical about the intermixing of business and philanthropic interests, and usually exerted influence at the highest political levels behind closed doors.

Venture philanthropy funding from the BMGF increasingly influences civil society movements,69 universities and researchers,70 and government programs. This influence leads to modification of mandates, scientific research foci, and methodological approaches and also squeezes out more critical analyses. Indeed, it is widely known that the BMGF – via the Seattle-based Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, which it bankrolls – “claims for itself a core WHO role: ‘diagnosing the world’s health problems and identifying the solutions.”71 Meanwhile, critics within UN agencies, civil society organizations, and academia are silenced or excluded, depicted as holding outdated views. For instance, a Gates-funded Evaluation Report of the Scaling Up Nutrition multi-stakeholder initiative portrayed those who raised conflict-of-interest concerns as harboring “phobias” and “hostile feelings” towards industry, which could “potentially sabotage the prospects of multi-stakeholder efforts to scale up nutrition.”72

Another telling illustration is a 2017 high-level Memorandum of Understanding between the BMGF and the German development agency BMZ. This MOU commits BMGF and the BMZ to join forces in advancing the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through “revitalization” of global “partnership” approaches. Among other effects, this MOU opens up BMZ’s large network of contacts to the BMGF and invites staff exchanges between the organizations.73 If this MOU becomes a model for future government-foundation relations, it will further upend democratic and accountable decision making in the global health and development sphere.

Philanthrocapitalism Redux: Comparing the RF and the BMGF

Philanthropic largesse and the social-entrepreneurial mission of twenty-first century billionaires are today touted as unparalleled, as though capable of “sav[ing] the world.”74 This is underscored by the ever more welcoming and enabling environments for corporate investment and “charitable” sponsorship of the UN’s flagship SDGs, adopted in 2015 with the stated aim of ending poverty, reducing inequality, and advancing health, social well-being, and environmental sustainability.75 The claims for selfless, philanthropic generosity merit critical consideration,76 for which comparisons with the past are illuminating.

Philanthropy circa 1900 derived from the profits and exploitative practices of leading oil, steel, railroad, and manufacturing interests. Similarly, the colossal profits earned during the 1990s and 2000s by investors in the information-technology, insurance, real estate, and financial sectors, as well as industries linked to mining, oil, and the military, were built on the rising inequality to which they contributed, abetted by massive, if often lawful, tax evasion.77 In both eras, profits were amassed thanks to depressed wages and worsening labor conditions; trade and foreign investment practices obstructing and weakening protective regulations; illicit financial outflows; externalizing and transferring the social and environmental costs of doing business onto the public and future generations; and tacit support for military regimes to guarantee access to valuable raw materials and commodities.78

On the eve of launching his foundation, Bill Gates’s net worth exceeded that of 40% of the US population.79 The company he created, and in which he and the BMGF still hold shares, was recently accused of heavily lobbying against reforms that would curtail corporate tax evasion.80 Gates remains the wealthiest of eight megabillionaires who are as rich as the poorest half of humanity.81 Yet these men are celebrated for their philanthropy rather than scrutinized for their business practices.

The tenet that business models can resolve social problems – and are superior to redistributive, collectively deliberated policies and actions developed by elected governments – rests on the belief that the market is best suited to these tasks, despite ample evidence to the contrary. Still, the BMGF’s support of such models and incentives diverges from that of the RF. Although following a business model and undergirding an expanding capitalist system, the RF explicitly called for public health to be just that: in the public sphere.

Tax-deductibility of philanthropic donations is an affront to democracy. The belief that charitable giving can change the world is just another variant of the decidedly undemocratic doctrine that the rich know best. Whereas “governments used to collect billions from tycoons and then decide democratically what to do with it,”82 today they cede agenda setting about social priorities to the class that already wields undue economic and political power.

Applauding and encouraging the munificence of elites will not create equitable, sustainable societies. Ironically, people living on modest incomes are proportionately far more generous than the rich, often donating money and time at considerable personal sacrifice, without receiving comparable recognition or tax breaks for their contributions.83 A century ago, the millions of people involved in social and political struggles for decent, fairer societies were far more skeptical than many are today about big philanthropy and its effect on public policy making, including policies about public health.

In short, a plutocratic health governance system with authoritarian features is becoming entrenched. Fading independent critical media have facilitated the philanthrocapitalist onslaught, with the emergence of an engineered “consensus” claiming that the world’s problems can only be solved through “partnerships” of all “stakeholders.”

By contrast, through the 1940s, the RF supported a small number of leftwing advocates of social medicine even as it privileged a medicalized, reductionist approach; the BMGF, however, remains largely impervious to opposing viewpoints. As the premier international health organization of its day, the RF had an overarching purview and was instrumental in establishing the centrality of the field of public health to the realms of economic development, nation-building, diplomacy, scientific diffusion, and capitalism writ large, while institutionalizing lasting, if problematic, patterns of health cooperation. The BMGF, for its part, while reliant on the public sector to deliver many of its technology-focused programs,84 appears largely indifferent to the survival of the “public” in public health.

“A Rich Man’s World, Must it Be?”

These many examples demonstrate that capitalism trumps philanthropy – or “love of humankind,” from the word’s ancient Greek roots – making philanthrocapitalism an oxymoronic enterprise indeed. The pivotal, even nefarious, role it has played in global health depends on gargantuan resources enabled by profiteering of titanic proportions amidst relentless ideological assaults on redistributive approaches, within a pro-corporate geopolitical climate of dominant, if currently cracking, global capitalism.

In the twenty-first century, it may still be a rich man’s world, but we need not settle for a rich man’s agenda. Collective activism to overturn philanthrocapitalism’s hold on global health is an urgent necessity. This effort should draw from, and build upon, the resistance to the UN’s promotion of “multi-stakeholder partnerships” and neoliberal global restructuring since the 1990s.85 Those actors who have contributed either unwittingly, or through silent assent, or even with active collaboration, to the global health plutocracy also share responsibility in re-democratizing it. Governments and UN agencies need to take their public mandates seriously. Scientists, scholars, activists, civil servants, international organization staff, parliamentarians, journalists, trade unionists, and ethical thinkers of all stripes have a duty to question and counter philanthrocapitalists’ unjustified influence; work together for accountability and democratic decision-making: and reclaim a global health agenda based on social justice rather than capital accumulation.

Acknowledgments

This piece was adapted and updated from: Anne-Emanuelle Birn,”Philanthrocapitalism, Past and Present: The Rockefeller Foundation, the Gates Foundation, and the Setting(s) of the International/ Global Health Agenda,” Hypothesis 12, no. 1 (2014): e8. We are grateful to Sarah Sexton, Alison Katz, Esperanza Krementsova, Mariajosé Aguilera, Jens Martens, and Lída Lhotská for their support and suggestions.

Notes

- Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (New York: Random House, 1998); William H. Page and John E. Lopatka, The Microsoft Case: Antitrust, High Technology, and Consumer Welfare (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

- William Wiist, Philanthropic Foundations and the Public Health Agenda (New York: Corporations and Health Watch, 2011), http://corporationsandhealth.org/2011/08/03/philanthropic-foundations-and-the-public- health-agenda/.

- Josep Lluís Barona, The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920–1945 (New York: Routledge, 2015).

- Judith Richter, Public-Private Partnerships and International Health Policy Making: How Can Public Interests Be Safeguarded? (Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, Development Policy Information Unit, 2004); Jens Martens and Karolin Seitz, Philanthropic Power and Development: Who Shapes the Agenda? (Aachen/Berlin/Bonn/New York: Brot für die Welt/Global Policy Forum/MISEREOR, 2015). https://www.globalpolicy.org/images/pdfs/Newsletter/newsletter_15_09_25.pdf.

- Matthew Bishop and Michael Green, Philanthrocapitalism: How Giving Can Save the World (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009). The original 2008 subtitle of Philanthrocapitalism volume, How the Rich Can Save the World, was changed in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis when it became apparent that the rich were harming rather than saving the world. Website: http://philanthrocapitalism.net/about/faq/

- George Joseph, “Why Philanthropy Actually Hurts Rather Than Helps Some of the World’s Worst Problems,” In These Times, December 28, 2015, http://inthesetimes.com/article/18691/Philanthropy_Gates-Foundation_Capitalism.

- David Callahan, The Givers: Money, Power, and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017).

- This is magnified by other actors, in particular the World Economic Forum’s Global Redesign Initiative (WEF GRI), a corporate-led campaign that set out in 2009 to restructure the architecture of global decision-making so that UN agencies become just one of many “stakeholders” in “multi-stakeholder governance.” See Judith Richter, “Time to Turn the Tide: WHO’s Engagement with Non-State Actors and the Politics of Stakeholder-Governance and Conflicts of Interest,” BMJ 348 (2014): g3351, http://www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g3351; Flavio Valente, “Nutrition and Food – How Government for and of the People Became Government for and by the TNCs,” Transnational Institute, January 19, 2016, https://https://www.tni.org/en/article/nutrition-and-food-how-government-for-and-of-the-people-became-government-for-and-by-the .

- Andrew Carnegie, “The Gospel of Wealth,” North American Review 148 (1889): 653- 654. Carnegie later expanded this presentation to a book, published in

- John Ettling, The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981).

- Philanthropy also played an ambiguous role in struggles over government- guaranteed social protections by promoting “voluntary,” charity-based, efforts instead. To this day, both non-profit and for-profit private sectors in the United States play a large part in providing social services, curbing the size and scope of the U.S. welfare state and giving private interests undemocratic purview over social welfare.

- John Farley, To Cast Out Disease: A History of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation, 1913–1951 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004).

- Marcos Cueto, Missionaries of Science: The Rockefeller Foundation and Latin America (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994).

- Iris Borowy, Coming to Terms with World Health: The League of Nations Health Organisation 1921–1946 (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2009).

- Anne-Emanuelle Birn and Theodore M. Brown, eds., Comrades in Health: U.S. Health Internationalists Abroad and at Home (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013).

- League of Nations Health Organisation, “International Health Board of the Rockefeller Foundation,” International Health Yearbook (Geneva: LNHO, 1927).

- Adapted from Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Marriage of Convenience: Rockefeller International Health and Revolutionary Mexico (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2006), p.

- Birn, Marriage of Convenience.

- Anne-Emanuelle Birn, “Backstage: The Relationship Between the Rockefeller Foundation and the World Health Organization, Part I: 1940s–1960s,” Public Health 128, no. 2 (2014): 129-40.

- The RF resurfaced at this time to play a small but instrumental role in promoting selective primary health care (SPHC), emphasizing scaled-down “cost-effective” approaches, such as immunization and oral rehydration; these became the main plank of UNICEF’s child survival campaigns during the 1980s under its director, James Grant, the son of an eminent RF man, creating bitter and lingering divisions between WHO and UNICEF.

- Nitsan Chorev, The World Health Organization Between North and South (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012).

- Judith Richter, Holding Corporations Accountable (London, Zed Books, 2001).

- Eeva Ollila, “Global Health Priorities – Priorities of the Wealthy?” Globalisation and Health 1, no. 6 (2005): 1-5.

- Debabar Banerji, “A Fundamental Shift in the Approach to International Health by WHO, UNICEF, and the World Bank: Instances of the Practice of ‘Intellectual Fascism’ and Totalitarianism in Some Asian Countries,” International Journal of Health Services 29, no. 2 (1999): 227-59.

- Deborah Hardoon, “An Economy for the 99%,” Oxford: Oxfam International, 2017, https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/economy-99.

- Martens and Seitz, Philanthropic Power and

- Page and Lopatka, The Microsoft Case.

- Mark Curtis, “Gated Development – Is the Gates Foundation Always a Force for Good?” (London: Global Justice Now, 2016), http://www.globaljustice.org.uk/resources/gated-development-gates-foundation-always-force-good .

- In 2006, Buffett pledged US$31 billion in shares to be paid in

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “Global Health Data Access Principles,” April 2011, https://docs.gatesfoundation.org/Documents/data-access-principles.pdf.

- Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Yogan Pillay, and Timothy H. Holtz, Textbook of Global Health, 4th edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Bishop and Green,

- Linsey McGoey, No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy (New York: Verso Books, 2015).

- David McCoy, Gayatri Kembhavi, Jinesh Patel, and Akish Luintel, “The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Grant-making Program for Global Health,” Lancet 373, no. 9675 (2009): 1645-1653; Birn, Pillay, and Holtz, Textbook of Global Health. Between 1998 and 2016, for example, Seattle-based PATH (Program for Appropriate Technology in Health), PATH Drug Solutions, and PATH Vaccine Solutions – together the BMGF’s largest grantee – received over US$2.5 billion, about 12 percent of the global health and global development grants it

- Birn, Pillay, and Holtz, Textbook of Global Health.

- Bill Gates, “Prepared Remarks – 2005 World Health Assembly, http://www.gatesfoundation.org/speeches-commentary/Pages/bill-gates-2005-world- .

- Anne-Emanuelle Birn, “Gates’s Grandest Challenge: Transcending Technology as Public Health Ideology,” Lancet 366, no. 9484 (2005):

- Anne-Emanuelle Birn, Laura Nervi, and Eduardo Siqueira, “Neoliberalism Redux: The Global Health Policy Agenda and the Politics of Cooptation in Latin America and Beyond,” Development and Change 47, no. 4 (2016): 734-59.

- Results for Development, “Our Approach,” http://www.r4d.org/about-us/our-

- Martens and Seitz, Philanthropic Power and Development.

- Jacob Levich, “The Gates Foundation, Ebola, and Global Health Imperialism,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 74, no. 4 (2015): 704-42.

- David Stuckler, Sanjay Basu, and Martin McKee, “Global Health Philanthropy and Institutional Relationships: How Should Conflicts of Interest Be Addressed?” PLoS Medicine 8, no. 4 (2011): 1-10.

- Jessica Hodgson, “Gates Foundation Sells Off Most Health-Care, Pharmaceutical Holdings,” The Wall Street Journal, August 14, 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125029373754433433.html.

- William Muraskin, “The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization: Is It a New Model for Effective Public-Private Cooperation in International Public Health?” American Journal of Public Health 94, no.11 (2004): 1922-25.

- “Merck Exec to Be Gates Foundation CFO,” Reuters, March 31, 2010, http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSN3120

- See McCoy, et al., “The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Grant-making Program for Global Health.” A few investigative journalists and online sites serve as courageous exceptions.

- William New, “Pharma Executive to Head Gates’ Global Health Program,” Intellectual Property Watch, September 14, 2011, http://www.ip-org/2011/09/14/pharma-executive-to-head-gates-global-health-program/.

- Page and Lopatka, The Microsoft Case.

- Curtis, “Gated Development.”

- New, “Pharma Executive to Head Gates’ Global Health ”

- Anubhuti Vishnoi, “Centre Shuts Health Mission Gate on Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,” The Economic Times, February 9,

- Arun Gupta and Lída Lhotska, “A Fox Building a Chicken Coop? – World Health Organization Reform: Health for All, or More Corporate Influence?” APPS (Asia & Pacific Policy Society) Policy Forum, December 5, 2015, http://www.policyforum.net/a-fox-building-a-chicken-coop/; Catherine Saez, “WHO Engagement With Outside Actors: Delegates Tight-Lipped, Civil Society Worried.” Intellectual Property Watch, May 24, 2016, https://www.ip-watch.org/2016/05/24/who- engagement-with-outside-actors-delegates-tight-lipped-civil-society-worried/.

- Donald G. McNeil Jr., “The Campaign to Lead the World Health Organization,” New York Times, April 3, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/03/health/the-campaign-to- lead-the-world-health-organization.html.

- World Health Organization, “Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors,” WHO, 2016, Document 10, http://www.who.int/about/collaborations/non-state-actors/A69_R10-FENSA- en.pdf?ua=1.

- Ann Zammit, “Development at Risk: Rethinking UN-business Partnerships,” Geneva, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, 2003, http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/%28httpPublications%29/43B9651A57149 A14C1256E2400317557? OpenDocument; Richter, Public-Private Partnerships.

- Marian L Lawson, “Foreign Assistance: Public-Private-Partnerships (PPPs)”, (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2013), http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41880.pdf

- Judith Richter, “We the Peoples” or “We the Corporations”? Critical Reflections on UN-Business “Partnerships” (Geneva: IBFAN/GIFA, 2003), http://www.ibfan.org/art/538-pdf; Eeva Ollila, Global-health Related Public-Private Partnerships and the United Nations (Globalism and Social Policy Programme (GASPP), University of Sheffield, 2003), http://www.aaci-india.org/Resources/GH-Related-Public-Private-Partnerships- and-the-UN.pdf.

- Katerini T. Storeng, “The GAVI Alliance and the ‘Gates approach’ to health system strengthening.” Global Public Health 9, no. 8 (2014): 865-879.

- William Muraskin, Crusade to Immunize the World’s Children: The Origins of the Bill and Melinda Gates Children’s Vaccine Program and the Birth of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, (Los Angeles, CA: Global Bio Business Books, 2005).

- Anne-Emanuelle Birn and Joel Lexchin, “Beyond Patents: the GAVI Alliance, AMCs, and Improving Immunization Coverage Through Public Sector Vaccine Production in the Global South,” Human Vaccines 7, no. 3 (2011): 291-2.

- Doctors Without Borders, The Right Shot: Bringing Down Barriers to Affordable and Adapted Vaccines (New York: MSF Access Campaign, 2015).

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), “Large Scale Food Fortification,” http://www.gainhealth.org/programs/initiatives/.

- Lucy Jarosz, “Growing Inequality: Agricultural Revolutions and the Political Ecology of Rural Development,” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 10, no. 2 (2012): 192-199.

- Germán Velásquez, “Public-Private Partnerships in Global Health: Putting Business Before Health?,” (Geneva: South Centre, 2014), http://www.southcentre.int/wp- content/uploads/2014/02/RP49_PPPs-and-PDPs-in-Health-rev_EN.pdf.

- Eeva Ollila, “Restructuring Global Health Policy Making: The Role of Global Public- Private Partnerships,” in Maureen Mackintosh and Meri Koivusalo, eds., Commercialization of Health Care: Global and Local Dynamics and Policy Responses (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

- Catherine Saez, “Geneva Health Campus: New Home for Global Fund, GAVI, UNITAID by 2018,” Intellectual Property Watch, February 14,

- Sandi Doughton and Kristi Helm, “Does Gates Funding of Media Taint Objectivity?” The Seattle Times, February 19, 2011.

- Martin Kirk and Jason Hickel, “Gates Foundation’s Rose-Colored World View Not Supported by Evidence,” Humanosphere, March 20,

- Shack/Slum Dwellers International, “Partners,” http://knowyourcity.info/partners/.

- Callahan, The Givers.

- McNeil, “The Campaign to Lead the World Health Organization.”

- Judith Richter, “Conflicts of Interest and Global Health and Nutrition Governance: The Illusion of Robust Principles,” BMJ 349 (2014): g5457, http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g5457/rr.

- BMZ & the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “Memorandum of Understanding between the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,” Berlin: BMZ; Seattle: BMGF, http://www.bmz.de/de/zentrales_downloadarchiv/Presse/1702145_BMZ_Memorandum.

- Bishop and Green, Philanthrocapitalism.

- UN Division for Sustainable Development, “Sustainable Development Goals,” 2016, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org.

- McGoey, No Such Thing.

- Linda McQuaig and Neil Brooks, The Trouble with Billionaires (London: Oneworld Publications, 2013).

- William I. Robinson, Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Humanity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- Russell Mokhiber and Robert Weissman, Corporate Predators: The Hunt for Mega- Profits and the Attack on Democracy (Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 1999).

- Curtis, “Gated Development.”

- Hardoon, “An Economy for the 99%.”

- Robert Reich cited in Peter Wilby, “It’s Better to Give than Receive,” New Statesman, March 19, 2008, http://www.newstatesman.com/society/2008/03/philanthropists-money.

- Alex Daniels and Anu Narayanswamy, “The Income-Inequality Divide Hits Generosity,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, October 5, 2014, www.philantropy.com/article/The-Income-Inequality-Divide/152551.

- David McCoy and Linsey McGoey, “Global Health and the Gates Foundation – in Perspective,” in Owain D. Williams, Simon Rushton, eds., Health Partnerships and Private Foundations: New Frontiers in Health and Health Governance (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave, 2011).

- Kenny Bruno and Joshua Karliner, “Tangled Up In Blue: Corporate Partnerships at the United Nations,” San Francisco, Transnational Resource & Action Centre, 2000, http://www.corpwatch.org/article.php?id=996; Richter, “We the Peoples”; Judith Richter, “Building on Quicksand: The Global Compact, Democratic Governance and Nestlé,” Geneva, IBFAN/GIFA, CETIM, Berne Declaration, 2004, http://www.cetim.ch/product/building-on-quicksand-the-global-compact- democratic-governance-and-nestle/.