The response to Chagas disease still needs inclusive protocols, sustainable and adequate financing and does not have a robust portfolio of investigation of new treatments and diagnosis. Beyond that, production capacity and supply of Benznidazole (BZN) medication is far from being minimally sufficient. The price factor also strongly impacts access to medication. A point deserving attention in the analysis of BZN’s prices is the need, as in the response to other diseases in general, to maintain competition as a factor of market regulation

by Eloan Pinheiro *, Lucia Brum ***, Renata Reis **, Juan-Carlos Cubides ***

*Consultant in Public Health Policy; ***Brazilian Medical Unit (BRAMU), Médecins Sans Frontières–Brazil; **Advocacy and Interinstitutional Relationships, Médecins Sans Frontières-Brazil

Chagas Disease

A Reflection on the Lack of Access to Treatment

Introduction

Chagas disease or American trypanosomiasis is a potentially fatal disease caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi and endemic in 21 countries in the Americas region, being mainly transmitted by Triatominae insects. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes Chagas as a neglected disease due to two elements: the fact that mainly affects people who are unaware of their rights to health and low investment in innovation and development, especially in access to diagnosis and treatment [1].

Over the past 30 years, there has been a significant reduction in the number of cases of the disease due to actions to combat the vector developed by national programs under the intergovernmental initiatives in the Americas. However, little progress has been made in relation to the component of care and treatment for people who were already infected. Currently the WHO estimates that there are approximately 6 million people infected by Chagas disease in the world, which generally face known limitations in access to diagnosis and treatment [2].

Benznidazole (BZD) and Nifurtimox are the only drugs available for the treatment of Chagas disease in the world. Launched in 1967 and 1972, respectively, these drugs quickly proved to be effective in the treatment of acute infections, but were largely ignored for the treatment of chronic infections due to the high frequency of undesirable side effects, low apparent cure rates and a lack of international consensus on the diagnostic criteria and parasitological cure.

Unfortunately, the portfolio of molecules currently investigated for this neglected disease is reduced, reducing as well the possibility of developing new treatments. Nifurtimox is manufactured by Bayer Health Care as Lampit® and Benznidazole was produced by Roche as Rochagan® or Radanil®. Originally, Roche had the registration for the drug in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Uruguay, Peru, Nicaragua and Japan. After Roche stopped its BNZ production on April 2003, the Brazilian laboratory LAFEPE figured as the only global producer, providing the finished product directly to Bolivia, Paraguay, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Honduras, El Salvador, Chile, Switzerland, Mexico, Argentina and Brazil.

Brazilian production always had problems in both the normative aspect (especially in relation to greetings rules of health authorities) and in relation to production. The lack of supply on the active ingredient (API-BZD) led to the shortage of the drug in 2011. After years of monopoly drug production by LAFEPE, another BZD producer stepped in: the Argentine laboratory ELEA part of the international group Chemo. This new production is not enough to cover the necessities in countries with high burden of the disease and bring to the picture another variable to analyze on the private production of drugs: high costs.

Access to BZD: Needs vs. Production Capacity

The annual production capacity of the two producers is a ton (1,000 kg) per year each, and may double this quantity, in exceptional cases. Thus, the current annual production capacity of API varies between 2,000 kg and 4,000 kg/year and the latter quantity is a possibility.

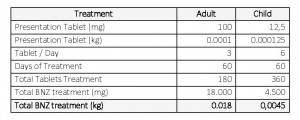

For treating an average adult patient; tablets of 100 mg in 3 daily doses for 60 (sixty) days are required. It takes 180 (one hundred eighty) tablets for an adult to complete their treatment equivalent, to 0.018 kg of raw materials. Pediatric use also requires sixty 60) days to comply with the treatment, taking tablets of 12.5 mg, 6 times per day; this is equivalent to 0.0045 kg of raw material (Table 1).

Table 1. API-BZD quantitative estimation necessary for treatment of an adult and a child

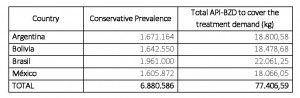

The number of patients and API-BZD required in order to provide their treatments in four endemic countries in Latin America, namely Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Mexico is shown in Table number 2. Considering the amount noted for the treatment of adults and children only in the selected countries, 77.4 tons of API-BZD are required while the production mentioned above (4.4 tons of total maximum capacity of both producers) responds only to 5.7% of the actual need.

Table 2. API-BZD quantitative estimation necessary to meet the demand of BZD medicines in countries with larger epidemiological indices [3]

Right to Health and Access to Essential Medicines

The right to enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health even though it is crystallized in various international legal instruments today is far from assured for a substantial part of the population. This right was first proclaimed in the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1946, whose preamble defines health as “a state of complete physical well-being, mental and social and not merely the absence of disease”. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 also brings health as part of the right to an adequate standard of living (Art. 25)[4]. The right to health was also recognized as a human right in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, 1966, and is reinforced in numerous international treaties and documents.

In recent years, it has been given greater attention to the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Thus, the organs that monitor the implementation of human rights treaties, the WHO and the UN Human Rights Council has sought to observe and report misrepresentation of a wider range of rights, among them the right to access essential medicines. Over time, it became increasingly apparent the direct link between access to essential medicines and the progressive realization of the right to health. This broad global recognition imposed the translation of this recognition in public policy enforcement of this right.

Chagas disease is an emblematic case of disrespect to the right of access to treatment according to the statements mentioned. Considered one of the most widely distributed diseases in the Americas, Chagas disease completed in 2009 a hundred years of its discovery and even today lacks inclusive protocols, is not sustainable and adequate funding, capacity and supply BZD medicine is far to be minimally sufficient.

The information exposed before (Table 1) brought illustrative data on the deficit of the world production capacity of BZD taking into account the four Latin American countries with high prevalence making urgent to discuss the issue. Currently the existing amount of BZD in the world allows only treat about 111,000 patients (taking into account the real world production of 2 tons of raw material per year) or about 222,222 patients (if produce 2 tons more per year); this equates to only 3.22% of treatments currently needed in the referred countries.

In summary, many lobbying efforts and medical advocacy can be undertaken by social organizations, affected groups of people, but a pressure to governments and producers must accompany those actions, so that the productive capacity of BZD be expanded and the current monopolized production of BZD be stopped. Over the years, given the experience on treatment of Chagas disease in multiple countries it is important to acknowledge the socio-cultural and political-economic aspects involving inequity issues, which are often not considered. The disease affects the most vulnerable and deprived populations in countries were the problem remains under a huge invisibility. Unfortunately, the perception of many public managers is that Chagas is the disease of backwardness and poverty, so it is better to hide it than to face it; when the real solution lies on breaking the cycle of neglection by offering appropriate diagnosis and treatment to all in need.

References

[1]. Lee, B.Y., Bacon, K.M., Bottazzi, M.E., Hotez, P.J., 2013. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: a computational simulation model. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13 (4), 342–348.

[2]. Available http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/, Source: WHO, 2010.

[3]. Institute for One World Health. Estimative on BZD for T. cruzi infected people in the Americas. 2007

[4]. Available http://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/por.pdf