Urban population growth in Africa will continue to exert strong pressures on the delivery of healthcare services. The diseases of poverty thrive in conditions of high population density, poverty, poor infrastructure and wealth disparities. Community-directed interventions (CDI) for neglected tropical diseases have been demonstrated by the WHO/TDR research agenda to improve coverage, empower communities and build stakeholder capacity in rural Africa. We offer this formative study of community capacity in post-conflict, pre-Ebola Monrovia as a case study of the utility of formative community-based collaborations. We used community-based participatory research to assess the feasibility of CDI for urban Liberia. The communities ranked malaria, diarrheal/water-borne illnesses, and acute respiratory infections (ARI) as the highest priorities. Furthermore, communities perceived these health priorities in the overall context of water & sanitation/hygiene/solid-waste management. While the health delivery system is donor-driven and under-resourced, we found stakeholder and community enthusiasm for partnering to achieve health goals. Resilience and shared accountability are critical features of sustainability which should be supported by health policy and insinuated into priorities seeking to build social capital and community capacity for health-care delivery

Richard A. Nisbett*†, Stephen B. Kennedy*, Fulton Q. Shannon II‡, and C. Benjamin Soko¥

*University of Liberia-Pacific Institute of Research and Evaluation, Africa Center (UL-PIRE)

†WVS Tubman University, Harper Liberia

‡Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Monrovia Liberia

¥National Public Health Institute of Liberia, Monrovia Liberia

Policy Implications for Community-based Interventions to Strengthen Healthcare Delivery, Based Upon a Formative Study of Community Capacity in Urban Monrovia, Liberia

Keywords: Urban Health, Health System Strengthening, Diseases of Poverty, Community-based Participatory Research, Community Capacity, Shared Accountability

INTRODUCTION

Because global health deals with transboundary issues which require collective action, it is by necessity a multi-lateral and multi-sectoral endeavor. One of the more salient global health issues in the 21st century will be the rapid increase of people living in cities where growth has outpaced the ability to provide essential infrastructure (UN-Habitat 2010a). In the next quarter century, the population of the Developing World is projected to increase by more than 30% to almost 7 billion, with 90% living in urban areas which today are experiencing increased levels of poverty. The Population Reference Bureau estimated that in 2007 for the first time in history, the majority of the global population lived in urbanized areas (PRB 2008).

Urbanization and Health System Strengthening in Africa

In Africa, the annual urban growth rate is projected to be 3.4% with perhaps 60% of all Africans, about 1.2 billion, living in urban areas by 2050 (UN-Habitat 2010b). Furthermore, this UN-Habitat report projected that while the populations of all one million-plus cities in Sub-Saharan Africa are expected to expand by an average of 32%, seventy percent (70%) of all African urban population will occur in smaller cities of less than 500,000. Such growth will exert tremendous pressure for services and infrastructure. The Executive Director of UN-Habitat has stated that:

No African government can afford to ignore the ongoing rapid urban transition taking place across the continent. Cities must become priority areas for public policies, with hugely increased investments to build adequate governance capacities, equitable services delivery, affordable housing provision and better wealth distribution. (Ibid.)

The infectious diseases of poverty (DOP) thrive on high population density, poor infrastructure, and wealth inequities. As has been asserted by social scientists, disease occurs within a context of lives fraught with complexity (Allotey et al. 2010) which has been understudied and underappreciated in the past (Madon et al. 2007). Defining urban health systems as “the determinants and outcomes of health and the activities that link them,” Harpham (2009) reviewed recent evidence for the vulnerability of the urban poor, the deteriorating health of the urban poor in Africa and studies suggesting that urban populations sometimes have greater health risks and mortality than their rural counterparts (see Montgomery et al. 2004) despite the presumed better availability, access and appropriateness of health services. While there is a tendency to think of urban poverty and disease burden in terms of slum dwellings, using data from 85 Demographic and Health Surveys Montgomery and Hewett (2004) found considerable household wealth heterogeneity in Developing World cities, i.e., that as a rule, poor urban households do not tend to live in uniformly poor communities but often in mixed communities. Harpham presented evidence that regardless of access or heterogeneity, the poor received low-quality care from both the private and the public sectors. Taken together, these data and findings underscore the need to strengthen urban health systems.

The renewed focus on health systems strengthening (HSS) has resulting in guiding principles (Swanson et al. 2010), strategies to integrate the control of DOPs into health-care delivery systems (Gyapong et al. 2010), and addressing “capability traps” (Pritchett et al. 2010). Various recent reports and declarations have reaffirmed the urgency of re-committing to primary health care (PHC) in order to strengthen healthcare delivery, outlining strategies and approaches and all emphasizing the roles of community engagement and stakeholder partnerships to integrate and harmonize programs (WHO 2006, WHO 2008a, WHO 2008b). Compelling evidence from community-based (CBI) and community-directed interventions (CDI) for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) has demonstrated persuasive health gains from multi-stakeholder programs involving community participation. Pioneered by WHO/TDR, the CDI strategy for building multi-lateral partnerships and community capacity building has shown through a rigorous multi-country protocol to not only improve coverage and adherence for a variety of NTDs but also to build community and health system competence in rural Africa (WHO/TDR 2008). One desired outcome of such approaches is building linkages and creating shared accountability (Azim et al. 2018). Without improved accessibility, affordability and HSS the present obstacles and disparities characterizing urban health will most likely result in increased risk factors, incidence and prevalence for vulnerable, marginalized persons as well as their more affluent neighbors in mixed communities.

It is our view that these challenges must be addressed at the policy and implementation levels.

Emerging and resurging DOPs underscore the urgency of both HSS and shared accountability. During the 2013-2014 West African Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Epidemic, frontline communities took the lead on EVD and deserve much of the credit for stemming the epidemic (Kennedy and Nisbett 2015; Nisbett and Vermund 2014; Fallah et al. 2017). Here, we present a case study of communities in urban Monrovia to demonstrate the potential of formative studies to empower communities, build stakeholder linkages and create the added value of shared accountability.

Case Study Objectives

The purpose of our formative phase study was to assess urban communities in greater Monrovia in order to ascertain the potential for adapting and testing the CDI approach for urban Africa. The primary objective was to determine if the CDI process as deployed in rural Africa for delivery of health interventions will be feasible for urban healthcare delivery in underserved and marginalized communities. The operational objectives for the formative phase study were: (1) to document the current delivery process of existing health interventions; (2) to identify poorly served urban communities; (3) to identify potential stakeholder and community networks which could contribute to CDI implementation; (4) to identify community priorities that can be addessed by the CDI process; (5) to explore the community networks and delivery mechanisms suituable for urban CDI; (6) to engage stakeholdes in contemplating the value of the CDI process for post-conflict urban Monrovia; (7) to explore mechanisms and community partnerships for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) and impact evaluation of CDI; (8) to map the extant resources at all levels of the system from local health committees and providers to the national level; (9) to determine with communities and stakeholders the types of interventions desired; and (10) to conduct situational analyses and generate sufficient baseline data to inform the decisions regarding how best to implement urban CDI.

METHODS

The Liberian Civil War (1989-2003) destroyed health infrastructure and workforce capacity and created many challenges for research into health system functioning. Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, very few evidence-based community health initiatives had been undertaken. We assembled a team of 12 project staff based at UL-PIRE located in greater Monrovia (Montserrado County) to conduct a formative investigation in partnership with colleagues at the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW).

Capacity Building for Community-based Participatory Health Research

Several weeks, cumulatively, were devoted to staff training and skills-refresher exercises on the methods and techniques of rapid ethnograpy, qualitative approaches, and community-based participatory research (CbPR) (Minker and Wallerstein 2008, Ulin et al. 2004, WHO 2003). Topics and techniques included document review, community mobilization and meetings, key informant interviews (KII), focus group discussions (FGD), transect and asset mapping, photodocumentation, and field journaling (diary entries).

Community Selection and Activities

We deployed a two-pronged design: formative phase-stage 1 was exploratory and primarily relied on KIIs and the available health system data and documents for extant communities. Formative phase-stage 2 was an in-depth investigation using a more extensive skillset of CbPR tools. Based on previous community-based and social-marketing interventions conducted by UL-PIRE, we targeted ten (10) underserved communities in urban Monrovia for exploratory studies (Stage 1). We categorized communities in greater Monrovia into either “interior” Monrovia (inland areas) or “coastal” Monrovia (marine or estuarine environments). We collated and analyzed the available (if sparse) census, GIS demographic data, and available government and NGO documents in order to select the 10 communities. We used KIIs of government officials, community leaders and health stakeholders to generate qualitative data on these 10 communities. Using a weighted formula (government health facility present/absent, functional leadership structure, vulnerability to environmental health threats, population density, geography [e.g. discreteness to eliminate contamination of interventions due to proximity/contiguity], and our previous experiences implementing health interventions), we selected five (5) focal communities from the original 10 communities for in-depth CbPR (Stage 2) assuming that we would implement randomized case-control studies for a subsequent intervention phase. The five focal communities were selected to sample (i) two communities of equivalent structure and relatively low population density in “interior” Monrovia; (ii) two communities of equivalent and relatively high population density in “coastal” Monrovia; and (iii) an outlier community judged to have exceptional leadership by which to better understand social capital, community capacity vis-à-vis the four (4) proposed match-control communities.

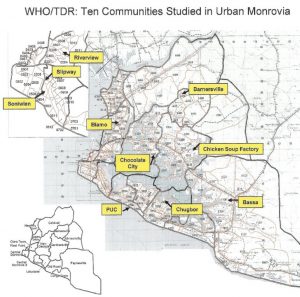

Figure 1. SELECTIVE COMMUNITIES IN URBAN MONROVIA

RESULTS

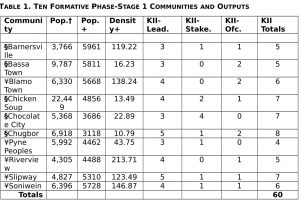

The primary results are presented in several tables and discussed for each operational objective. Table 1 shows the population parameters and KII totals for each of the 10 communities. The population density for the coastal communities is about three and one-half times that for the interior communities.

Key: †Population from LISGIS 2010; +Population from HIC 1997; +Density from HIC 1997 = pop./acres;

- “Interior Monrovia” = Barnersville, Bassa Town, Chicken Soup, Chocolate City, Chugbor = 36.52 Pop. Den. Vs. ¥“Coastal Monrovia” = Blamo Town, Peoples, Riverview, Slipway, Soniwein = 133.31 Pop. Den.

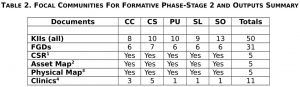

Table 2 gives the outputs for the five communities in Stage 2. These communities were subjected to more intensive and extensive interactions.

Key: Stage 2 Focal Communities were Chocolate City (CC); Chicken Soup Factory (CS); People’s United Community (PU); Slipway (SL); Soniwien (SO); 1CSR—a typed report summarizing the Team’s observations in the community; 2Asset Map—a typed description of the salient health threats and opportunities for each community; 3Physical Map—a hand-drawn geographic map showing environmental health threats, community facilities (e.g, health, education, religious, community office, etc.); 4Clinic Tables—summary tables of selected health indicators as collected by the local clinics and reported to the MoHSW.

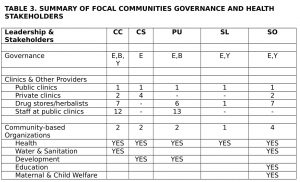

Table 3 summarizes the governance structure and stakeholder analyses for the five focal communities (Objectives 1, 3, and 5.).

Key: Community abbreviations same as Table 2; E= Executive board or council; B= Block leaders structure; Y=Youth Committee

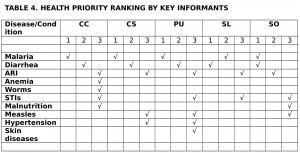

Table 4 gives a ranking of health priorities by communities (Objectives 4 and 9). These rankings come from KIIs of government health officials, health providers and stakeholders and community key informants.

Key: Community abbreviations same as Table 2; Ranked in order by KII response; multiple entries per rank order is due to ties (frequencies)

DISCUSSION

The Study Area

Since the 1980 coup, Liberia has experienced a quarter-century of declining health services. The Civil War of 1989-2003 brought about destruction of the healthcare infrastructure and decimation of the healthcare workforce. The war resulted in the death of perhaps one-tenth and the external- or internal- displacement of about one-third of the pre-war population of three million. Recent surveys in the immediate post-conflict setting (UNDP 2006, CSFSN 2006) estimated a maternal mortality rate of 974/100,000, a child mortality rate of 195/1,000 and for those aged <5 years, stunting at 39% and wasting at 7%. Malaria is both holoendemic and hyperendemic with the highest incidence occurring in urban and peri-urban environments during the rainy season. During the conflict and post-conflict periods, most health services were provided by INGOs resulting in service discontinuities, a top-down emphasis, and consequently a lack of capacity building for key stakeholders from the national to the community levels.

The best estimate for the current population of greater Monrovia is about 900,000-1,000,000 (personal communications based on DHS 2007, LISGIS 2009), with a population density ranging from 10-400 persons/sq. km. The highest population density geographically occurs in the constricted coastal zones such as West Point (a peninsula formed by the Atlantic Ocean and Mesurado River), New Kru Town (hemmed in by the Atlantic and St. Paul’s River), and “Central Monrovia B,” the central city inland from the coastal diplomatic enclaves of the Mamba Point area. (See Figure 1). Most of the other zones are highly dense and congested as well but due to the terrain and topography the population densities are lower. Greater Monrovia contains much uninhabitable land due to the confluence of the St. Paul’s and Mesurado Rivers which yield a huge inland area of interior estuarine mangrove swamp and inundated lowlands.

Community Capacity

Community capacity is both an input and outcome of health interventions. It consists of human and material resources utilized as assets. The MacArthur Foundation defines it as a community’s ability to mobilize energy and talents to secure outside resources and foster quality-of life; McLeroy defines it as community characteristics which enable it to identify, mobilize and address public health problems (in DiClemente et al. 2002). For our purposes in this formative phase study, we have viewed community capacity as a community’s perception of its public health needs, its health assets and its willingness to collaborate with partners to improve its own well-being.

THE LIBERIAN HEALTHCARE DELIVERY SYSTEM

The following description and data regarding the government of Liberia (GoL) health system come from several internal and unpublished grey documents shared with our team during this study. These documents include: (1) The Republic of Liberia National Health Policy (2007); (2) The Republic of Liberia National Health Plan 2007-2011 (2007); (3) MoHSW Annual Report (2009); (4) Basic Package of Health and Social Welfare Services for Liberia (2008); (5) MoHSW Community Health Committee Operational Guidelines (2007); (6) GoL Overview of Poverty Reduction Strategy for the Health Sector (2008); (7) USAID PMI Malaria Operational Plan for Liberia (2010); and the Monserrado County Health & Social Welfare Budget 2009-2010 (2009).

Health Facilities and Access to Health Care

By 2006, MoHSW reported that country-wide 18 hospitals, 50 health centers, and 286 health clinics were functional. By 2009 there were 163 functional GoL health facilities (28% of the total number of health facilities country-wide) and 257 NGO facilities; in Montserrado County, there were 37 functional health facilities, 21 NGO facilities and 120 private facilities. However, there are few available data on health service utilization and access. The Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy (2006) reported that 41% of the population had access to health services. Most sources and authorities suggest “low service consumption and gross imbalances” across Liberia.

Healthcare Delivery Services and Resources

Healthcare delivery is severely fragmented and donor-dependent upon vertical programs funded by external sources. The current health care delivery system is strained and under-funded with dozens of INGOs and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) delivering a variety of health services in both the urban and rural areas. Community-based delivery of care, based on the CDI model, is not practiced in the urban core of Monrovia. Now moving towards recovery, Liberia is uniquely positioned to benefit from enhanced implementation strategies focused on community-based partnerships such as CDI.

The Government of Liberia (GoL) National Health System

The National Health Delivery System is organized in a hierarchical manner. PHC is considered the foundation of the health system. The National Health Policy states emphatically that: “Interventions will focus on community empowerment—seeking to enhance a community’s ability to identify, mobilize and address the issues that it faces to improve the overall health of the community” [emphasis added].

Leadership/Governance Architecture

The MoHSW is in charge of health services within the territorial frontier of Liberia and is headed by the Minister. The Minister of Health has four deputies to assist him in day-to-day operations of the health delivery system. These deputies are: the Deputy Minister for Administration who oversees all administrative matters of the Ministry, the Deputy for Planning and Human Development, the Deputy for Social Welfare, and the Deputy Minister and Chief Medical Officer (CMO). All of these deputies have an assistant deputy minister who serve as technical arm and support for their activities. The CMO is the highest decision-making person when it comes to Health Services, and is assisted by two Assistant Ministers: the Assistant for Curative services and the Assistant for Preventive Services. The Assistant Deputy Chief Medical Officer for Curative services assigns all Medical Doctors, Physician Assistants, Registrar Nurses, Midwifes and Nurse Aids in all health facilities in Liberia. The Assistant Minister for Preventive Services is responsible for all public health activities, overseeing: Malaria Control, TB control, National Aids Program, etc. The CMO and the Assistant Chief Medical Officer for Preventive Services are required to be MDs. All officers are political appointees.

Current Service Delivery System

The MoHSW, in line with the sector reform process, has restructured the health care delivery by putting in place a decentralized mechanism on the county level. The Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) is the “cornerstone” for health delivery in Liberia. This is a package of essential health services that is being implemented at both the facility and community levels. The BPHS is being fully implemented at all facilities across the country. Its implementation at the community level has started, but at a very slow rate. However, the post-EVD environment and establishment of a new national public health institute has done much to accelerate consensus and progress.

At the central level the Minister of Health is the first contact person for any health matter in the country. The Minister delegates responsibilities to the appropriate person in charge. For example, if it is health services matter it goes to the CMO for approval. The CMO will approve of the communication and then send it to either of the two deputies according to the nature of the subject. From the central office, the information will then go to the County Health Team (CHT). At the county health level, there is a County Health Officer (CHO) who is the head of the health care system within their respective county. Also, at the county health level, there is a Community Health Director, Clinical Supervisor and Officer-in-Charge (OICs) at the clinics/facilities (GoL public). The Clinical Supervisor conducts supervisory visits at all government health facilities. The OICs report to the Clinical Supervisor, and the Clinical Supervisor report to the CHO and the CHO report to the offices of the CMO and all these are sent to the appropriate departments.

Within the County, there is surveillance system set up for all priority diseases. This effort is supported by the WHO and all reports from these activities are channeled through the Department of Epidemiology and onward to the WHO. There is a County Surveillance Officer, and District Surveillance Officer. They also work within the communities and collect surveillance reports for all priority diseases from various clinics and report them directly to the Epidemiology Department at the Central Level of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare.

The OIC of the catchment health facility, through the Government Community Health Volunteer (gCHV) focal person at the facility, has oversight responsibilities for the health facility area. This person could be a Nurse-Aid at the health facility and other person appointed as gCHV focal person in the Health Facilities. He or she ensures that reports from the CHVs and CHC (Community Health Committee, see below) are forwarded to the OIC, who then passes the report along to the clinical supervisor. The clinical supervisor reports to the CHT. The CHT ensures that in-service training is provided on continual basis. The focal person and OIC at the catchment health facility liaise with district officer and county health team (CHT) and report is sent to CHT. The focal person also maintains records on the composition and performance of each CHC and CHVs. Other program staff members in the ministry liaise with the focal person and OIC in implementation of their programs at community level. The Ministry of Health considers Community Health Volunteer (CHV) as an important component of health care delivery system of Liberia. This is reflected in the national health policy and the basic package for health services. The Basic Package for Health Services (BPHS) identifies specific activities that can be at the community level and by the community. However, in practice there is no funding for CHVs.

The community health services policy states that a functional CHC is a necessary condition for effective community health volunteers: “CHVs are more likely to be effective in active, mobilized communities; it is not realistic to expect that CHVs, by themselves, can be active or empower a community that isn’t ready.” Since the CHV is selected and supervised administratively by the community, it is logical that there should be a structure in the community to perform this function in an orderly fashion. Therefore, MoHSW requires that Community Health Development Committee and/or CHC should be revamped, activated or established as a criterion for selection, training, and supervision of the CHVs.

Community Health Development Committee/ Community Health Committee (CHC)

The Community Health Development Committee or the Community Health Committee, where applicable, is the umbrella body of the catchment area and has oversight responsibility. They are to provide support to the CHCs in their catchment areas. The CHC is a body selected by the community in collaboration with Ministry of Health and Social Welfare through the County Health Teams and the Community Health Development Committee. The CHC oversees and supports the functions/duties of the Community Health Volunteers in their respective community. All health services going into the community are channeled through the Clinical Supervisors of both partners (as in the case of Merlin, MTI, etc) and the CHT to the facilities and then to the community through their Community Health Committee (CHC) if present. Reports from the community are channeled through the same medium to the Headquarters (MoHSW and partners, e.g. Merlin).

Salient Issues

Beyond the service delivery aspects of the Liberian Health System, we discuss below several relevant, critical issues regarding provision of health services country-wide and to our selected communities. It is important to emphasize that Liberia is in a rebuilding phase and the majority of the planning documents and policy statements represent idealized programs—like community-based initiatives—that are not yet, or only in an incipient stage of becoming, operationalized.

Health Care Workforce

It has been noted how the Liberian civil conflict severely disrupted the healthcare delivery system. One of the primary disruptions was the loss of trained health care workers through morbidity, mortality or being forced into refugee status. The minimum level of workforce density to achieve the MDGs is 2.5 health workers per 1000 people. The global average is 9.3 while the average for Sub-Saharan Africa is 2.4. Recent WHO data yield an estimate of 0.08 for Liberia: MDs = 0.03, Nurses = 0.18, Midwives = 0.12, Public health workers = 0.04, and community health workers = 0.02.

Health Information/Surveillance

As delineated in the section above regarding the Healthcare Delivery System, there is a routine surveillance system. The MoHSW has also prioritized establishing a proactive Health Management Information System (HMIS). The HMIS will be able to generate reports and trend analyses for the following areas: financial information, human resources, physical assets and equipment inventories, healthcare delivery service statistics and the incipient surveillance system.

Medical Products, Vaccines, & Technologies

The framework to manage pharmaceutical and medical supplies is contained within the National Drug Policy and is centered on the National Drug Service (NDS). Supplies are supported by multilateral donors and private-public partnerships such as the Global Fund. The NDS warehouse is fully stocked and located in Monrovia.

Financing & Budgets

The national health policy has stipulated the suspension of user fees for the immediate future. The MoHSW budget anticipates about 35% of necessary funding coming from GoL revenues with the remainder coming from external sources in the form of donor restricted and unrestricted funds. The current MoHSW directory lists 65 NGOs accredited to work in the health sector.

Typically, in the post-conflict annual budgets, government expenditure on health care in Liberia is about 17-19% of the GoL budget. The MoHSW total receipts for CY 2009 was US$29,361,565. By revenue source, GoL funds account for 34.7%, Pool funds for 21.7%, the Global Fund for 15%, Earmarked donor funds for 26.2%, and Other donor funds for 2.5%. By program account for CY 2009, Curative was 72.8%, Preventative was 8.5%, Social welfare was 5.1%, Planning was 2.4%, Vital statistics was 0.7%, and Administration was 10.4%. The total budgeted for Preventative was US$1,713,541.

The Montserrado County Health Department budget for FY 2009 was a total of US$387,049. However, this allocation is restricted to non-personnel expenses only (infrastructure rehabilitation and maintenance, vehicle maintenance, electrical generators, medical and office supplies, and meetings/trainings. In 2009, the USAID-financed Rebuilding Basic Health Services (RBHS) project concluded from costing studies that annual cost projections of clinics without and with laboratories should be between US$34,261 and US$36,250, respectively. The RBHS study estimated the total cost of providing primary and secondary care at health centers to vary from US$36,620 to US$59,083.

Summary of the Operational Objectives

Regarding the operational objectives for the formative phase, we have summarized our data for each, integrating the perspectives from the KII (Key Informant Interviews) and FGD (Focus Group Discussions) survey instruments.

Objective #1–To document the current delivery process of existing health interventions. Our analyses of GoL/MoHSW documents and interviews of cognizant officers and division managers have facilitated the creation of an overview of the healthcare delivery system in greater Monrovia. The MoHSW has curative and a preventative divisions. The former is marginally functional in the capital city while, for the most part, the latter has not yet been operationalized in post-conflict Liberia. While treatment at government clinics is often at minimal or no cost for diagnosis, the challenges for acquiring pharmaceuticals, etc. are formidable for the typical person. Often, as noted in Harpham (2009), drugs are not available at public clinics and unafforadable at private clinics or pharmacies. In some communities, health education activities are conducted but the quality, availability and uptake are extremely variable. There were no CDI-like programs conducted by the GoL or NGO partners in any of the 10 communities we studied.

Objective #2–To identify poorly served urban communities. Virtually all communities in greater Monrovia are extremely underserved. Typically, there is a single GoL clinic serving each community and a few of the communities we studied had 2-5 private providers. The GoL clinics are required to report a broad range of data regarding surveillance, diagnostics utilized, health education activities, etc. However, the surveillance data we summarized for each clinic were sparse and incomplete. The most reliable data were for malaria testing and treatment—confirming the health priorities from KIIs and FGDs conducted to elicit perceptions regarding priority health threats.

Objective #3–To identify potential stakeholder and community networks which could contribute to CDI implementation. We conducted a stakeholder analysis and situational analysis for each community. Most communities have under-utilized assets and resources but few are health-oriented organizations. Several of the communities have taken the initiative to form their own Community Health Committee (CHC) and two of our five focal communities have Water & Sanitation committees and designated Community Health Workers (CHW). Overall, while there is a dearth of local health partners, we were energized by the leadership in most communities which sought to address salient health issues. The five focal communities we selected exhibited a demonstrated commitment to improve health outcomes and reduce disease burden.

Objective #4–To identify community priorities that can be addessed by the CDI process. During both Stage 1 and Stage 2, we conducted over 110 Key Informant Interviews and 30+ focus group discussions. The ranked priorities across communities were: malaria, diarrheal & water-borne diseases, respiratory diseases and reproductive health (STIs & MMR). For “malaria,” we attempted to triangulate by (1) using probes in KIIs and FGDs to determine informant’s perceptions of malaria symptoms and signs, (2) reviewing surveillance data from the community clinics, and (3) seeking the conclusions of OICs regarding the prominent health threats. The GoL clinics are required to report a broad range of data regarding disease surveillance/diagnostics, attendance at health education activities, availability of drugs and supplies, etc. However, the surveillance and reporting data we summarized for each clinic were spotty and incomplete.

While the more “rural” vector-borne/zoonotic NTDs addressed by the multi-country TDR CDI study were infrequent, we do see a need for surveillance and case identification/treatment due to great urban-rural-urban mobility in present-day Monrovia. However, the majority of CDI programs (malaria treatment, ITNs, Vitamin A, and DOTs for TB), as well as ACT for IPT and Cb HIV/AIDS ART would be most beneficial and welcomed. As part of the KII and FGD process, after explaining the successes and approaches of CDI, the response was uniformly positive at the community level.

Objective #5–To explore the community networks and delivery mechanisms suituable for urban CDI. As for Objective #3, we found under-utilized networks and resources. On the whole, these Monrovia communities are merely trying to rebuild and negotiate the post-conflict environment. On the positive side, communities are demanding input and ownership in their own health. On the negative side, much capacity building, empowerment and delivery infrastructure for CDI will need to be part of the intervention strategy.

Potential stakeholders include: INGOs with their local implementing partners, the County Health Team (community health department), GoL Community Health Facility, Private Clinics, Pharmacy & drug stores, Faith-based groups & schools, Community Health & Watsan Committees, Market Women Association, Women’s Cooperatives & Organizations, Natural helpers (midwives, nurses aides, drug-store owners, herbalists, traditional healers, etc.), Youth Committees, Cuttington University Program in Public Health, and University of Liberia Social Sciences Department. Every community indicated a willingness to provide in-kind resources (labor, food, land, etc.) as incentives to CHW or CHV. In fact, some are already providing meals for youth laborers for environmental clean-up. Also, see Objective # 7 below.

Objective #6–To engage stakeholders in contemplating the value of the CDI process for post-conflict urban Monrovia. The GoL stakeholders (Montserrrado County Health Team, OICs for GoL clinics, etc.) and the local CHCs/CHWs were most enthusiastic about the potential for CDI. The NGOs—both international and local—were less enthusiastic and over-stretched in the current environment. The non-health community partners (schools, faith-based organizations, etc.) represent a willing and educable resource.

Objective #7–To explore mechanisms and community partnerships for M&E and impact evaluation (IE) of CDI. At the present, there is very little capacity for M&E and IE. Designing urban CDI for Monrovia will entail considerable training and beta testing. On the other hand, one of our partners—the Graduate Program in Public Health at Cuttington University in Monrovia—is collaborating with our team in field testing demographic data generation and project implementation for nutrition. Since this partner has human resources (students enrolled in the program) and the desire to collaborate, we are optimistic that we can build effective M&E into a CDI program.

Objective #8–To map the extant resources at all levels of the system from local health committees and providers to the national level. We have constructed asset maps and stakeholder diagrams for each community as it relates to the GoL healthcare delivery system.

Objective #9–To determine with communities and stakeholders the types of interventions desired. We have used CbPR to identify priority health concerns and introduced the CDI concept. Cumulatively, the 5 focal communities prioritzed these “conditions:” (1) malaria, (2) water & sanitation/diarrheal diseases, and (3) respiratory illnesses. One salient limitation is the lack of an ethnograpy of disease symptoms and medical cosmology in these communities.

Objective #10–To conduct situational analyses and generate sufficient baseline data to inform the decision to implement urban CDI. We have conducted community and County situational analyses. However, we have not yet brought the National Drug Service or other key stakeholders like PMI, GFFTBAM, UNDP, etc. into the dialogue. This omission was intentional as the two lead investigators concurred that the post-conflict environment is not conducive to such discussions until we have something to offer on the table (“No cola nut, no pepper, No talk.”) We have baseline population data and malaria prevalence and incidence (spotty) but will need to generate household-level demographics (age and sex) as well as specific health indicators relevant to particular diseases at baseline. This information is presently nonexistant at the community level.

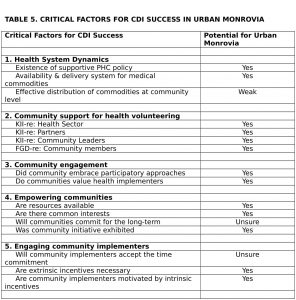

SUMMARY: Critical Factors, Capability Traps, and Community Capacity for CBI

Healthcare delivery in Liberia is presently donor-driven with scant government resources for CBI, CDI or CHCs. In the seminal multi-country rural study (WHO/TDR 2008), the teams identified several factors critical for successful CDI implementations. These included variables such as: health system dynamics, community support for health volunteers, community engagement, community empowerment, and engaging implementers. Integrating our data from KIIs, FGDs, and the document reviews, we have analyzed these same critical factors to inform the feasibility of CDI in urban Monrovia and present these in Table 5.

We have identified challenges and opportunities, barriers and bridges for CDI implementation in urban Monrovia, a resource-constrained setting. In view of the post-conflict/transitional setting, there appears to be genuine community capacity so we remain cautiously optimistic. The communities exhibit potential and willingness but doubtless are naïve regarding the workload, tenacity and sacrifices necessary to become effective partners over the long-term. One of the more formidable challenges that remains is workforce capacity building for our own UL-PIRE staff and the government implementers. Training for monitoring and evaluation are critical for successful delivery using CDI. Thanks to the efforts of WHO/TDR, CDI has been widely deployed in Sub-Saharan Africa. We feel that the approach would find great resonance and relevance in similarly resource-constrained settings in Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Pritchett et al. (2010) defined “capability traps” as persistent stagnation of administrative capability and designate these as a hindrance to development. The community-level enthusiasm in urban Monrovia for being proactive partners engaged in finding their own solutions and demanding services is encouraging but must be tempered by the realization that there are many capability traps to be overcome. We feel that “resilience,” as a critical feature of sustainability which acknowledges and absorbs change, must be built into any health intervention based on promoting bonding and bridging social capital. Maston (2001) defines resilience as good outcomes in spite of serious threats. Information regarding resilience (“adaptive capacity” according to Harpham) is essential for household health, community capacity/empowerment, and hence for HSS in urban Africa. Finally, we urge policy makers to prioritize formative studies such as the case study here. Such studies are easily interpolated into extant budgets and health initiatives. They facilitate exits from capability traps, empower communities, and build shared accountability.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR:

Richard A. Nisbett

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding support for this formative study was generously provided by the WHO/TDR. Supplemental travel and logistics support was provided by PIRE-USA and The University of South Florida College of Public Health. We are particularly grateful to the WHO/TDR community-based interventions unit and to our peers in The Urban Research Group (Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo) for their friendship, insights, leadership and expertise in community-directed interventions. Many individuals have made substantive contributions towards the development of the Urban Study Group’s Mombasa Protocol. For their support and encouragement, we’d be remiss in not mentioning by name the following for their many kindnesses and professional efforts to bring Liberia into this CBI network: Drs. Boatin, Homeida, Diarra, and Sommerfeld. Finally, we’d like to thank yet again the courageous people in urban Monrovian communities, having endured not only unfathomable tragedy and loss due to both Civil War and the EVD Epidemic, but also our incessant interruptions and invasions into their lives, responding always with patience and a cooperative spirit in our common quest to build a new Liberia.

REFERENCES

Allotey P, DB Reidpath, S Pokhrel (2010). Social sciences research in neglected tropical diseases 1: The ongoing neglect in the neglected tropical diseases. Health Research Policy & Systems 8:32: 1-8.

Azim T, B Tilahun, S Mullin (2018). Use of Community Health Data for Shared Accountability, MEASURE Evaluation, https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-18-238.

DiClemente RJ, RA Crosby, MC Kegler (2002). Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for Improving Public Health. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fallah M, Skrip LA, Raftery P, Kullie M, Borbor W, Laney AS, et al. (2017) Bolstering Community Cooperation in Ebola Resurgence Protocols: Combining Field Blood Draw and Point-of-Care Diagnosis. PLoS Med 14(1): e1002227. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002227.

Gyapong JO, M Gyapong, N Yellu, K Anakwah, G Amofah, M Bocharie, S Adjei (2010). Integration of control of neglected tropical diseases into health-care systems: Challenges and opportunities. Lancet 375:160-165.

Harpham T (2009). Urban health in developing countries: What do we know and where do we go? Health & Place 15:107-116.

Kennedy SB and RA Nisbett (2015). The Ebola epidemic: a transformative moment for global health, Bulletin World Health Organization 93(1):2.

Madon T et al. (2007). Implementation Science. Science 318(5857):1728-1729.

Maston AS (2001). Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. American Psychologist 56(3): 227-238.

Minkler, M and N Wallerstein (eds) (2008). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Montgomery MR and PC Hewett (2004). Urban poverty and health in Developing Countries: Household and neighborhood effects. Demography 42(3):397-425.

Montgomery M et al. (Eds) (2004). Cities Transformed: Demographic Change and Its Implications in the Developing World. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Nisbett RA, SH Vermund (2014). The Liberian Ebola Epidemic of 2014: Witchcraft, Ignorance and Tyranny of the Experts, October 1, 2014, RA Nisbett and SH Vermund, Springer-Verlag Public Health, http://www.springerpub.com/w/public-health/blog-the-liberian-ebola-epidemic-of-2014-witchcraft-ignorance-and-tyranny-of-the-experts/.

Prichett L, M Woolcock, M Andrews (2010). Capability Traps: The Mechanisms of Persistent Implementation Failure. Center for Global Development Working Paper #234.

Population Reference Bureau (2008). World Population Data Sheet.

Swanson RC et al. (2010). Toward a consensus on guiding principles for health systems strengthening. PLoS Medicine 7(12): E1000385.

Ulin, PR, ET Robinson, and EE Tolley (2004). Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

UN-Habitat (2010a). Hidden Cities: Unmasking and overcoming health inequities in urban settings. Geneva: WHO Centre for Health Development and United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

UN-Habitat (2010b). The State of African Cities 2010: Governance, Inequality and Urban Land Markets. Nairobi: United Nations Settlement Programme.

WHO (2003). Concepts and Methods of Community-Based Initiatives. Cairo: WHO Regional Office.

WHO (2006). Addis Abada Declaration on Community Health In the Africa Region. Brazzaville: WHO.

WHO (2008a). Ouagadougou Declaration on Primary Health Care and Health Systems in Africa: Achieving Better Health for Africa in the New Millennium. Brazzavile: WHO.

WHO (2008b). The World Health Report 2008—Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever. Geneva: WHO.

WHO/TDR (2008). Community-directed Interventions for Major Health Problems in Africa, A multi-country study final report. Geneva: WHO.