Nicaragua currently lags behind other countries in the LAC region as for the decline of teenage pregnancies, and although the adolescent fertility rate fell sharply between 1990 and 2000, the decline has slowed considerably

By Clara Affun-Adegbulu*

Intern and Research Assistant at Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp (ITM)

Teenage Pregnancy in Nicaragua

Towards Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

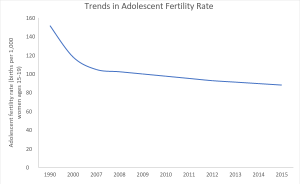

Nicaragua is doing well economically. In spite of the recent slowing of the global economy, the country has managed to maintain an above average level of growth within the Latin American and Caribbean region (LAC), cut poverty rates and make progress with achieving the SGDs (The World Bank 2017). This success story is however in danger of unravelling because of the stall in the decline of teenage pregnancies. Nicaragua currently lags behind other countries in the region, and although the adolescent fertility rate fell sharply between 1990 and 2000, the decline has slowed considerably.

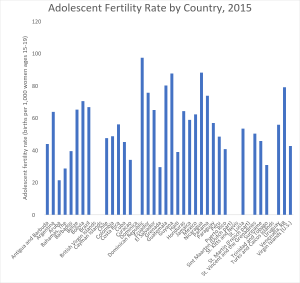

Adolescent fertility rates in the LAC region, 20151

Nicaraguan adolescent fertility rate, 1990-20151

According to La Federación Coordinadora Nicaragüense de ONG que trabajan con la Niñez y la Adolescencia (CODENI 2013)2 :

- Births among adolescents follows social gradient. For instance, adolescent fertility is 75% higher in rural areas, and 46% of uneducated teenagers are mothers.

- Sexual violence and a lack of access to appropriate sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information and services are the main causes of adolescent pregnancy.

- Pregnancy poses risks to the reproductive health of the adolescent mother and exposes her child to issues such as increased risks of perinatal mortality and delayed development.

- Adolescent mothers are more likely to stop their education early, be single mothers, have more children at shorter intervals and live in poverty.

Possible Public Policy Interventions

- Improve access to SRH information and services: Sex education should be offered as early as possible in schools, with a similar service provided in extra-curricular settings for children who are not in the school system. Vulnerable groups e.g. girls (and boys) in rural areas, should be targeted with tailored information.

- Reduce sexual violence: The prosecution of rapists should be prioritised, girls and their families should be educated about their rights, and the process of reporting crimes should be simplified and decentralised.

- Increase school enrolment: Primary and secondary school enrolment has been stalling in the last few years. Increasing school enrolment would have the double benefit of reducing adolescent pregnancy and preparing girls for future employment.

- Reintegrate adolescent mothers into the education system: teenage mothers are often excluded from the education system and later become unemployable because of their lack of skills. Providing these girls with ways of finishing their education would mean that they could break the cycle of poverty.

- Offer early social and medical intervention: Children of teenage mothers are at risk of poor health and social outcomes. Early intervention would mitigate this risk and reduce the inequalities and inequities that these children face.

The problem is multifaceted, however, and Nicaragua must resolve it if it is to continue its developmental trajectory unhampered and achieve SDGs such as:

- Goal 1: No poverty

- Goal 3: Good health and well-being

- Goal 4: Quality education

- Goal 5: Gender equality

- Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth

- Goal 10: Reduce inequalities

Bibliography

- The United Nations (UN). 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations Official Document: Resolution A/RES/70/1 adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Accessed June 1, 2017. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

- Unidad Técnica del Observatorio de Derechos Humanos de Niñas, Niños y Adolescentes de la Federación Coordinadora Nicaragüense de ONG que trabajan con la Niñez y la Adolescencia (CODENI). 2013. “Las niñas, niños y adolescentes cuentan.” Observatorio sobre derechos humanos de la niñez y la adolescencia nicaragüense. Boletín No. 5, Año 2, mayo 2013.

- The World Bank. 2016. LAC Equity Lab: Gender – Health. LAC Equity Lab tabulations using WDI – World Development Indicators and Health Nutrition and Population Statistics. Accessed May 30, 2017. http://dataviz.worldbank.org/t/LCSPP/views/Gender_health/Heatlh_crosstab?:embed=y&:display_count=no

- The World Bank. 2017. Nicaragua: Country at a glance. Last Updated April 10, 2017. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nicaragua/overview

——————————————————————

* Nurse and Public Health Masters student at the Medical University and University of Vienna. She is currently interning as a research assistant at the International Health Policy unit of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, working on a literature review project on health systems strengthening. Clara is particularly interested in global health and development policy