Health equity as a concept of minimizing health disparities among people, could be of utmost importance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Providing equity in health and participating in the acts of providing equitable healthcare have different aspects. Although this pandemic is not the first global-scale biological threat that humankind has faced, there is still some points to be further addressed. Deeming health as a public good, inevitably necessitates taking responsibilities for its fair provision. The aim of this study is to notify the public (policy makers, medical staff, and other individuals interested in the topic of health equity) about some strategies to consider the tenets of equity in health while managing the COVID-19 pandemic

By Erfan Shamsoddin

DDS, National Institute for Medical Research Development, Tehran, Iran

Substantial Aspects of Health Equity During and After COVID-19 Pandemic

A Critical Review

Background

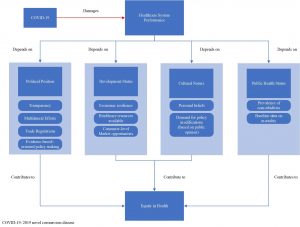

When emergencies occur, even principal ethos and tenets of any context might seem vulnerable to change under the imposed pressures. This has been the case for 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) regarding different aspects of health equity till today. Humankind has already dealt with contagious outbreaks and plagues, which have caused significant changes in the trajectory of scientific, political, and social sentiments regarding the disasters alike (1,2). Spanish flu (1918-1920), Smallpox outbreak (1972), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic (originated from 1980s), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (2002-2003), swine flu pandemic (2009-2010), and Ebola outbreak (2014-2016) are all some instances of such disasters (2). Appreciating all the efforts of healthcare systems around the world, there were also some major shortcomings and mistakes in response to these upsurges (1,3–5). Delayed provision of effective treatments, unclear and inefficient communication between the governments and their people, not providing enough education and awareness sources and even funds resources (previous to the occurrence of illnesses), are all among these wrongdoings (5,6). All these conditions seem to be partially or completely repeated for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) related disease. A highly contagious illness representing a basic reproduction number between 2 and 2.5, a crude mortality ratio between 3% to 4%, and an infectiousness phase starting at 2.3 days before the symptoms onset (7–9). Though substantial measures and means have been enhanced since the earlier crises (i.e. more technological advancements, swift communications, better healthcare resources and management, higher drug production figures, etc.), there still exists some discernible inconsistencies and differences within the management protocols among various countries and regions worldwide (6). Looked at from a health policy and management perspective, lowering the variations and increasing the commitment to certain cornerstones, which have been established and reinforced formerly, could ultimately lead to better results and more controllable political environments for populations and even governments (10). All in all, despite noticing the temporary nature of this issue, the provision of health in an equitable way seems to be rattling and reshaping over the period of COVID-19 outbreak. Such a claim could further be described in four separate domains: political position, development status, cultural tendencies, and baseline health status. Figure 1 depicts a schematic view of these components.

Figure 1

Political position

Political compass can greatly influence the initiation, implementation, and outcomes of the national and regional announced policies in response to plagues (11). Overall, this can be dissected into two major levels: national and international policies. Though the evidence could usually help in directing public policies, it is inevitably less effective when the event is unprecedented, at least in some aspects. Accordingly, although some official pandemic preparedness guidelines were available for Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), the birth of imminent COVID-19 has shown some different characteristics (12). Management strategies obeyed by the initially-virus-acquainted governments show variations from the past as well. Hong Kong, as an instance, have gone through quite similar conditions at 1997, during the H5N1 influenza outbreak. Total judgements on the performance of Margaret Chan, minister of health in Hong Kong at that time, are usually regarded as positive, well-led, and justifiable (13). Decimating domestic poultry seemed and still seems the best choice to prevent a pandemic (13–15). On the other hand, during the initiation of COVID-19, despite all the effective efforts and interventions implemented by the Chinese government after the spread of COVID-19 (16), lack of transparency _since announcing an outbreak as soon as possible, greatly impacts on the extent of public engagement_ and not following the WHO protocols about conducting full surveillance and control of avian outbreaks, was undeniable during the beginning of the crisis (17–19). Several explanations could be given as the cause of these shortcomings, namely, avoiding evidence-based decisions in favor of political biases, experimenting new solutions in response to an unknown biothreat (hoping to control the threat locally), and lazy governance (18,20). Healthcare is not a private commodity and every government should seek its provision as a public good (21). Consistently, multilateral efforts to address an outbreak or disaster could usually be considered as a critical step toward the resolution of a healthcare crisis in the least time possible (22–24). This will be eventually in favor of public health promotion. Instructions introduced by WHO are mainly in accord with the same principle, mainly emphasizing on travelling regulations, high-capacity surveillance measures and rapid reporting of positive cases to the international health organizations (25).

Evidence-based/-oriented policy making is another component which is highly under the impression of political stances in each country. More developed countries have already established and paved the evidence-assisted policy making pathways to follow. Nevertheless, developing countries have been getting more and more involved in this discipline in the last few years (26,27). Practicing this type of policies, might probably require training more specialists, more interactive international relations, and as a result, more interim costs. To take or not to take this road is basically determined by the authorities in force in developing countries _who mostly have been under long-term effects of narrative and rhetoric evidence in their decision makings. More developed countries on the other hand, can scrutinize and introduce modern patterns of the process. These new governance patterns usually get distributed via different medias (e.g. publications, news, professional events, international organization reports, etc.) which could serve as “scientific advice” for developing countries (28,29). The resiliency, nature, and ethos of healthcare systems, are therefore greatly maneuvered by the political position of the leaderships (30).

It is worth mentioning degree of autonomy and emancipation for trade markets and originator companies for they are regarded as gamechangers, hugely depending on each country’s political perspectives (31). The lucrative market of non-pharmaceutical and pharmaceutical products (including personal protection equipment, therapeutic/palliative drugs, and therapeutic/preventive vaccines) can be a tempting target for brand industries seeking out for-profit policies in the region during and after the occurrence of a plague (32). The final pathway of local and international economic investments and interventions is mainly determined and assessed during and in response to mishaps like COVID-19 (33).

Overall, the extent to which every nation will follow these rules and reach the goal of better health status, significantly depends on the principles on which their political compass is built upon.

Development status

The more industrialized and affluent a country/region is, the more capable it gets to resolve the financial issues during counteracting infectious outbreaks (34). Healthcare systems get established by developing critical care-provision infrastructures, gaining experiences (healthcare stewardship), providing and implementing technological advancements, building reliable international collaborations and coalitions, and scientific progression. Lack of such infrastructures in less-developed regions, could additionally exacerbate the issues imposed by a pandemic like COVID-19 (35,36). Since health is an integrated, intertwined matter worldwide, such disasters will inevitably exert their afflictions globally.

History is always repeating itself. After occurring an imminent pandemic like COVID-19, it is most likely that the first therapeutic/preventive treatment will get produced in an industrialized country, which would then support the mass production and lead the huge pharmaceutical markets in the near future. This was the case for 1918 influenza pandemic, H1N1 Influenza pandemic, and H5N1 avian Influenza (37,38). The request for compulsory benefit sharing (for pharmaceutical interventions) from developed countries led to constant rejections. Standard Material Transfer Agreement in 2009 _when negotiating for equitable access to influenza vaccines_ went through the same pathway and reached an evident destination, failure (37). Conceiving equity in health as a “charity” or “help” flowing from industrialized regions toward the less well-off, would probably result in similar outcomes in the future. Therefore, there need to be more accurate and comprehensive covenants between international parties aiming for equity in health throughout the world (39).

Another necessary fundament in healthcare systems, is the delivery. Provision of treatments in an effective and efficient way is of critical importance during infectious spreads, mostly affecting more susceptible patients (40). Individuals with special needs, systemic conditions, life-threatening and/or incurable diseases, women during the pregnancy period, older adults, and people under conditional restrictions (e.g. individuals restricted in jails) are all considered as susceptible people whom need to be specially treated by the governments during pandemics (41). Other than the pharmaceutical pools, constructive care delivery needs sufficient assets of human resources and healthcare facilities (36). Care providing centers with limited hospital beds, have already been facing an overflow of COVID-19 patients in several countries and districts (e.g. China, EU, USA, Middle East) (42–45). It can be said that the pandemic has damaged less-developed countries more severely in terms of value of fiscal crisis management costs as a share of country’s gross domestic product (GDP) (46). For example, defining fiscal stimulus packages and supportive funds to provide people with financial aids during the COVID-19 pandemic, has been of very different amounts among various countries (47).

All in all, the economic status and available resources of any country count as critical determinants of the COVID-19 management protocol.

Cultural norms

When enforcing local and domestic policies, the trail which the interventions will follow, and accordingly the empirical outcomes, are substantially affected by public opinion (48,49). The responsiveness of healthcare policies is perpetually being amended and directed by citizens’ predilections. Many current healthcare plans shift control and decision-making to the governments, whilst the final beneficiaries from these would be the citizens. The vast majority of people always care about the quality of care as the first aspect of healthcare provision in their regions. Increasing access, lowering the costs, and improving the choices are other considered variables for the quality of care (49). Nevertheless, the circumstances substantially differ in the case of a pandemic like COVID-19.

Public acceptance rate of the local and global policies concerning the health status is crucially affected by people’s personal beliefs (religion, etc.), ethnic prejudice, and culture (50). Inhabitants and citizens are actually the “performers” of the announced policies in each area, making them the most critical elements in directing the implementation of each intervention. For example, insisting on not obeying the curfews and not following the social distancing program (SDP) have been seen in various locations during the COVID-19 outbreak (51–54). Other countries, have redefined and reshaped some of the SDPs in order to be able to adjust the measures in accord with general people’s beliefs (55,56). These contextual policies have not shown promising results so far, as they fundamentally differ from the basic non-pharmaceutical interventions defined to cut the transmission routes of the virus (57). Epidemiologic advices relating to SDPs usually consider the following as critical tips: possibility of aerosol transmission, contact time necessary for contracting the COVID-19 during exposures, the minimum infectious dose, the degree of infectivity prior to onset of symptoms and its duration after recovery, seasonality effect, and immune responses in human beings (58). Looking at these factors, it seems challenging to gain people’s compliance after announcing new policies in a region to be obeyed, especially if the number of cases had been low (insignificant for the public) before the announcement date (59).

Two other important aspects of cultural beliefs during this pandemic, are the stigma about people who contracted the virus and have been cured (and the ones in contact with them, either directly or indirectly), and the origins of COVID-19 (60–62). Educating the citizens of any country is an utmost imperative to be addressed by their government. Accusing the Chinese residents of “unhealthy” eating habits or simply blaming the Wuhan virology lab as the causes and origins of SARS-CoV-2, would be superficial and not backed up by robust evidence till today.

Public health status

When a pandemic happens, regardless of what infrastructures are available, previous state of public health plays a critical role in the management phase (64). This refers to the therapeutic service-provision phase. In the case of COVID-19 pandemic, no definitive treatment is obtained yet (July 7th, 2020). This has led to a widespread human infection status (phase 5-6 of pandemic according to WHO’s classification of Influenza pandemic) and it is currently proceeding as the medical scientific teams seek highly effective treatment lines and possible candidates as preventive/therapeutic vaccines (65,66). This makes it indispensable for the medical staff to provide their patients with the best possible supportive and palliative treatments.

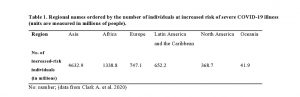

Generally, the presence of comorbidities can impose higher risks of exacerbation for the secondary illnesses or conditions. Results of a nationwide cross-sectional study conducted on 1590 Chinese patients, shows the same trend. Patients with any type of comorbidity have shown poorer clinical prognoses and resulted in less-favorable clinical outcomes. A greater number of comorbidities also correlated with poorer clinical outcomes and the most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (16.9%) and diabetes (8.2%) (67). Taking these two systemic conditions as the cornerstones for further inferences, data shows that the prevalence, and consequently the burden imposed by them differs throughout the world. Data from the year 2010 shows that 28.5% (95% confidence interval (CI), 27.3-29.7%) of the world’s adults had hypertension in high-income countries. This figure was 31.5% (95% CI, 30.2-32.9%) in low- and middle-income countries (68). Another study evaluating the burden of type 2 diabetes in 2011, stated that Asia accounted for 60% of the world’s diabetic population with India placing as the second epicenter of diabetes pandemic (69). More studies concerning COVID-19 have represented the following results: Portion of population at increased risk of contraction with SARS-CoV-2 virus was the highest in countries with older populations, African countries with high HIV/AIDS prevalence, and small island nations with high diabetes prevalence. Table 1 shows the results of regional names ordered by the number of individuals at increased risk of severe COVID-19 illness (units are measured in million(s) of people).

Table 1

These numbers can implicitly show the disparities among countries facing a global challenge like COVID-19. Although a lower share of population was displayed to be at risk for COVID-19 in African countries (3.1%) (compared to Europe with 6.5%), this simply implies the existence of much younger populations in African region. It was also mentioned that age-specific risks in African countries tend to be similar or higher than age-specific risks in European countries (70). Given that the opportunities and necessary basics to manage the disease are not similar worldwide, reporting the mortality occurrences could not simply be considered as the best choice to assess countries’ performances regarding the pandemic. Correspondingly, countries have been using some other measures to report their performance and productivity loss. Excess mortality (the number of deaths above and beyond what we would have expected to see under ‘normal’ conditions) or disability-adjusted life years (DALY) _which is usually adjusted by age, sex, and region (burden of COVID-19) are two examples of such measures (71,72).

Overall, when assessing the performance of each country against COVID-19 pandemic, everybody should first notice the baseline health status, initially available infrastructures, and the imperative costs of management for each country.

Discussion

Health equity is defined by the international society for equity in health (ISEqH) as: “the absence of systematic and potentially remediable differences in one or more aspects of health across populations or population subgroups defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically”. This definition implies the existence of systematic (rather than random or haphazard) differences pertaining to health equity. This allows for comparisons regarding health status alterations due to a specific disease/condition/illness, between the residents of geographically distinct (but socially alike) areas (73). However, as stated by P. Braveman and S. Gruskin in 2006, “a health disparity/inequality is a particular type of potentially avoidable difference in health or in important influences on health that can be shaped by policies; it is a difference in which a disadvantaged social group or groups … systematically experience worse health or greater health risks than the most advantaged social groups” (73). In consequence of accepting both these interpretations, we should continuously and perpetually seek for a reduction in health disparities/inequalities in the context of public health assessments. Health policies can actively change the values of health-related indices within populations, making them as the first-line actors responsible for creating/deteriorating health disparities. In a time of economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which is forecasted to lower the global economic growth by 0.5% in 2020 (from 2.9% in 2019 to 2.4% in 2020) (74), one might consider the issue of health equity as “unnecessary” or “unsuitable”. However, health equity is a universal term, highly intertwined with basic human rights and political justice. This would additionally stress the exigency of health equity during the COVID-19 outbreak, when underserved people around the world would probably need it the most. Some suggestions for not ignoring health equity amidst and after the pandemic are going to be introduced in this section.

Data gathering transparency is a key determinant in obtaining the best health-related outcomes. Reporting the true figures obtained from diagnostic tests gives the policy makers a correct insight about the situation in their sectors. This can later direct their decisions in shortcut ways to manage the outbreak promptly. Government-level transparency is also of utmost importance when it comes to reaching the best outcomes in the least possible time. Presenting the risks and hazards existing in the environment (without prioritizing politically-oriented aims over the health status of the nation) will attract public attention. This is going to be followed by more public engagement regarding the SPDs and participating to curb the viral transmission.

Another matter being suggested here is to provide open access to COVID-19 related topics for medical research teams around the world. There have already been some valuable efforts to gather and publish medical results free of fees worldwide. This is more necessitated when a plague threats the lives of humankind globally. Also, it is mutually accepted for all the physicians that providing their patients with the best possible treatment options, is a moral obligation. Following the same trend in other disciplines (technological advancement, political strategies, etc.) would definitely assist in resolving the troubles.

Two years after the Ebola outbreak (in 2014), the world bank announced the creation of the pandemic emergency funding facility (PEF) which is described as “a health insurance scheme for the world’s poorest countries and for qualified international responding agencies” (21). Although the coverage may seem low ($500m fund compared to the estimated 8.8 trillion dollars cost of COVID-19), the act itself lays a reliable pattern to scale up the response to such outbreaks in the world. Another example of introducing such acts is designing patent pools for pharmaceutical products. When settled as effective treatments against COVID-19, the demand for some limited types of drugs (antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, or anti-viral) will be soaring in the medical market. Suggesting effective ways to reach sustainable agreements between the brand industry and the generic competitors will increase the accessibility and affordability of the therapeutic/preventive agents in the near future. Patent pooling was suggested as one strategy to address the same issue for antiretroviral drugs (potential treatments for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (75). Designing similar interventions and not-for-profit-policies could immensely affect the fair availability of vaccines and drugs in the near future.

Lastly, educating residents about possible risks in nutrition patterns could be critical to halt the occurrence of other imminent outbreaks. A meeting report published by WHO in 2008 clearly claims the possibility of viral transmission via non-typical routes. Foodborne infection is introduced as a “frequent” viral transmission route. SARS-CoV and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) are described as resistant to (mild) food production processes routinely used to inactivate or control bacterial pathogens in contaminated foods (76). Regardless of literacy rate in a country, specific education in certain fields seems to be necessary to promote and reinforce the public engagement for some policies. Whenever there would be sufficient and robust evidence to claim a scientific critique about the origins of SARS-CoV-2, modifying Chinese residents’ nutrition patterns, which are engraved in them during several generations, might only be possible by extensive and persistent long-term education to achieve significant results. This claim is not limited to the Chinese nation and would be applicable to all kinds of risky dietary patterns around the globe.

Conclusion

Perceiving health as a public good obliges all governments to participate in the act of providing equity in health globally. Given that the favors will eventually return to their own nations, these acts should be done by any means available to the healthcare systems. Governments should refrain from political biases and cultural prejudices and reinforce the healthcare infrastructures as they are all necessary steps for achieving health equity.

References

- Castillo-Chavez C, Curtiss R, Daszak P, Levin SA, Patterson-Lomba O, Perrings C, et al. Beyond Ebola: Lessons to mitigate future pandemics. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(7):e354–e355.

- Huremović D. Brief History of Pandemics (Pandemics Throughout History). In: Psychiatry of Pandemics [Internet]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-030-15346-5_2.pdf

- Del Rio C, Hernandez-Avila M. Lessons from previous influenza pandemics and from the Mexican response to the current influenza pandemic. Arch Med Res. 2009 Nov;40(8):677–80.

- Barry JM. Pandemics: avoiding the mistakes of 1918. Nature. 2009 May;459(7245):324–5.

- Dionisio D. Lessons from the Ebola crisis | Future Virology [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/full/10.2217/fvl.15.16

- Barry JM. Pandemics: avoiding the mistakes of 1918. Nature. 2009;459(7245):324–325.

- Gandhi M, Yokoe DS, Havlir DV. Asymptomatic transmission, the Achilles’ heel of current strategies to control COVID-19. Mass Medical Soc; 2020.

- World Health Organization. Influenza and COVID-19 – similarities and differences [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-similarities-and-differences-covid-19-and-influenza?gclid=CjwKCAjwxev3BRBBEiwAiB_PWG2GvQcGhIpuuvvW5Njm5NlnGOc1uNoqsSyeycYev_W-VpJs65xmdxoC-hoQAvD_BwE

- He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020 May;26(5):672–5.

- Thompson KM. Variability and uncertainty meet risk management and risk communication. Risk Anal. 2002;22(3):647–654.

- Kabbani N. Pandemic politics: Does the coronavirus pandemic signal China’s ascendency to global leadership? [Internet]. Bookings. 2020. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/pandemic-politics-does-the-coronavirus-pandemic-signal-chinas-ascendency-to-global-leadership/

- Yella Hewings-Martin. How do SARS and MERS compare with COVID-19? [Internet]. 2020. Available from: Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus

- Evidence-based medicine and the governance of pandemic influenza: Global Public Health: Vol 7, No sup2 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17441692.2012.728239

- The politics of bird flu: The battle over viral samples and China’s role in global public health | John Benjamins [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/journals/10.1075/jlp.8.3.07mac

- Shuchman M. Improving Global Health — Margaret Chan at the WHO. N Engl J Med. 2007 Feb 15;356(7):653–6.

- From China: hope and lessons for COVID-19 control – The Lancet Infectious Diseases [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(20)30264-4/fulltext

- Zhu Y, Fu K-W, Grépin KA, Liang H, Fung IC-H. Limited Early Warnings and Public Attention to Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China, January-February, 2020: A Longitudinal Cohort of Randomly Sampled Weibo Users. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020 Apr 3;1–4.

- Ang YY. When COVID-19 meets centralized, personalized power. Nat Hum Behav. 2020 May;4(5):445–7.

- Zhang L, Li H, Chen K. Effective Risk Communication for Public Health Emergency: Reflection on the COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) Outbreak in Wuhan, China. Healthcare. 2020 Mar;8(1):64.

- Brett D. Schaefer. The World Health Organization Bows to China [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/commentary/the-world-health-organization-bows-china

- Stein F, Sridhar D. Health as a “global public good”: creating a market for pandemic risk. BMJ [Internet]. 2017 Aug 31 [cited 2020 Jul 2];358. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/358/bmj.j3397

- Preparing for the Next Influenza Pandemic [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2692546/

- Fedson DS. Preparing for Pandemic Vaccination: An International Policy Agenda for Vaccine Development. J Public Health Policy. 2005 Apr 1;26(1):4–29.

- McCloskey B, Dar O, Zumla A, Heymann DL. Emerging infectious diseases and pandemic potential: status quo and reducing risk of global spread. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014 Oct 1;14(10):1001–10.

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for investigation of cases of human infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). 2013 Jul; Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/MERS_CoV_investigation_guideline_Jul13.pdf?ua=1

- Uneke CJ, Ezeoha AE, Ndukwe CD, Oyibo PG, Onwe F. Development of Health Policy and Systems Research in Nigeria: Lessons for Developing Countries’ Evidence-Based Health Policy Making Process and Practice. Healthc Policy. 2010 Aug;6(1):e109–26.

- Behague D, Tawiah C, Rosato M, Some T, Morrison J. Evidence-based policy-making: The implications of globally-applicable research for context-specific problem-solving in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Nov 1;69(10):1539–46.

- Sanderson I. Evaluation, Policy Learning and Evidence-Based Policy Making. Public Adm. 2002;80(1):1–22.

- International Network for Government Science Advice. International Network for Government Science Advice [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.ingsa.org/resources/

- Blendon RJ, SteelFisher GK. Commentary: Understanding the Underlying Politics of Health Care Policy Decision Making. Health Serv Res. 2009 Aug;44(4):1137–43.

- Pauly LW. Capital Mobility, State Autonomy and Political Legitimacy. J Int Aff. 1995;48(2):369–88.

- Dionisio D, et al. For-profit policies and equitable access to antiretroviral drugs in resource-limited countries [Internet]. ResearchGate. [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238158536_For-profit_policies_and_equitable_access_to_antiretroviral_drugs_in_resource-limited_countries

- Tashanova D, Sekerbay A, Chen D, Luo Y, Zhao S, Zhang T. Investment Opportunities and Strategies in an Era of Coronavirus Pandemic [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2020 Apr [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Report No.: ID 3567445. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3567445

- Yamada T. Poverty, Wealth, and Access to Pandemic Influenza Vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2009 Sep 17;361(12):1129–31.

- Fedson DS, Dunnill P. Commentary: From Scarcity to Abundance: Pandemic Vaccines and Other Agents for “Have Not” Countries. J Public Health Policy. 2007 Sep 1;28(3):322–40.

- Oshitani H, Kamigaki T, Suzuki A. Major Issues and Challenges of Influenza Pandemic Preparedness in Developing Countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 Jun;14(6):875–80.

- Fidler DP. Negotiating Equitable Access to Influenza Vaccines: Global Health Diplomacy and the Controversies Surrounding Avian Influenza H5N1 and Pandemic Influenza H1N1. PLOS Med. 2010 May 4;7(5):e1000247.

- Alan Sean Johnson NPASJ, Mueller J. Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” Influenza Pandemic [Internet]. ResearchGate. [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11487892_Updating_the_Accounts_Global_Mortality_of_the_1918-1920_Spanish_Influenza_Pandemic

- Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Apr 1;57(4):254–8.

- Hurt AC, Chotpitayasunondh T, Cox NJ, Daniels R, Fry AM, Gubareva LV, et al. Antiviral resistance during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic: public health, laboratory, and clinical perspectives. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Mar 1;12(3):240–8.

- Dionisio D, Esperti F, Vivarelli DM and A. Priority Strategies for Sustainable Fight Against HIV/AIDS in Low-Income Countries [Internet]. Vol. 2, Current HIV Research. 2004 [cited 2020 Jul 3]. p. 377–93. Available from: https://www.eurekaselect.com/91417/article

- Abdi M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Iran: Actions and problems. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 Jun;41(6):754–5.

- Johnson HC, Gossner CM, Colzani E, Kinsman J, Alexakis L, Beauté J, et al. Potential scenarios for the progression of a COVID-19 epidemic in the European Union and the European Economic Area, March 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020 Mar 5;25(9):2000202.

- Xiang Y-T, Zhao Y-J, Liu Z-H, Li X-H, Zhao N, Cheung T, et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: managing challenges through mental health service reform. Int J Biol Sci. 2020 Mar 15;16(10):1741–4.

- Volpato S, Landi F, Incalzi RA. A Frail Health Care System for an Old Population: Lesson form the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. J Gerontol Ser A [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 3]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/advance-article/doi/10.1093/gerona/glaa087/5823151

- Santos Porras B. Controlling COVID-19 will carry devastating economic cost for developing countries [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/controlling-covid-19-will-carry-devastating-economic-cost-for-developing-countries-139492

- Statistica. Value of COVID-19 fiscal stimulus packages in G20 countries as of June 2020, as a share of GDP [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107572/covid-19-value-g20-stimulus-packages-share-gdp/

- Page BI, Shapiro RY. Effects of Public Opinion on Policy. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1983;77(1):175–90.

- Fender E, Fishpaw M. Public Opinion on Health Care Policy | The Heritage Foundation [Internet]. 2019 Apr [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/public-opinion-health-care-policy

- Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020 May;4(5):460–71.

- Lewis C. Religious extremists who flout COVID-19 rules are doing a disservice to God’s creation [Internet]. National Post. [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://nationalpost.com/opinion/charles-lewis-religious-extremists-who-flout-covid-19-rules-are-doing-a-disservice-to-gods-creation

- Pinsker J. The People Ignoring Social Distancing [Internet]. The Atlantic. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-social-distancing-socializing-bars-restaurants/608164/

- Mishagina N, Laszlo S, March 31 ESO published on PO, 2020. The importance of new social norms in a COVID-19 outbreak [Internet]. Policy Options. [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2020/the-importance-of-new-social-norms-in-a-covid-19-outbreak/

- Wilson J. The rightwing Christian preachers in deep denial over Covid-19’s danger [Internet]. the Guardian. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/04/america-rightwing-christian-preachers-virus-hoax

- Raoofi A, Takian A, Akbari Sari A, Olyaeemanesh A, Haghighi H, Aarabi M. COVID-19 Pandemic and Comparative Health Policy Learning in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2020 Apr;23(4):220–34.

- Dynamic distancing plan to be launched for COVID-19 containment [Internet]. Tehran Times. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/448986/Dynamic-distancing-plan-to-be-launched-for-COVID-19-containment

- Nicola M, O’Neill N, Sohrabi C, Khan M, Agha M, Agha R. Evidence based management guideline for the COVID-19 pandemic – Review article. Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2020 May;77:206–16.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Contro. Considerations relating to social distancing measures in response to COVID-19 – second update [Internet]. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Contro; 2020 Mar p. 12. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-social-distancing-measuresg-guide-second-update.pdf

- Penrod E. How to convince skeptics to take the coronavirus seriously – Business Insider [Internet]. businessinsider.com. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-convince-skeptics-to-take-the-coronavirus-seriously-2020-3

- A guide to preventing and addressing social stigma associated with COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/a-guide-to-preventing-and-addressing-social-stigma-associated-with-covid-19

- Logie CH, Turan JM. How Do We Balance Tensions Between COVID-19 Public Health Responses and Stigma Mitigation? Learning from HIV Research. AIDS Behav. 2020 Jul 1;24(7):2003–6.

- JMIR – Creating COVID-19 Stigma by Referencing the Novel Coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” on Twitter: Quantitative Analysis of Social Media Data | Budhwani | Journal of Medical Internet Research [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.jmir.org/2020/5/e19301/

- Modifying the Eating Behavior of Young Children – Perry – 1985 – Journal of School Health – Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 3]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1985.tb01163.x

- CDC foundation. Public Health in Action [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/what-public-health

- Information NC for B, Pike USNL of M 8600 R, MD B, Usa 20894. THE WHO PANDEMIC PHASES [Internet]. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response: A WHO Guidance Document. World Health Organization; 2009 [cited 2020 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK143061/

- What Is the World Doing to Create a COVID-19 Vaccine? | Council on Foreign Relations [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-world-doing-create-covid-19-vaccine

- Guan W, Liang W, Zhao Y, Liang H, Chen Z, Li Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J [Internet]. 2020 May 14 [cited 2020 Jul 4];55(5). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7098485/

- Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-based Studies from 90 Countries. Circulation. 2016 Aug 9;134(6):441–50.

- Hu FB. Globalization of Diabetes: The role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care. 2011 Jun 1;34(6):1249–57.

- Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, Guthrie B, Wang HHX, Mercer SW, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2020 Jun 15 [cited 2020 Jul 4];0(0). Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30264-3/abstract

- Nurchis MC, Pascucci D, Sapienza M, Villani L, D’Ambrosio F, Castrini F, et al. Impact of the Burden of COVID-19 in Italy: Results of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and Productivity Loss. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(12):4233.

- Tracking covid-19 excess deaths across countries. The Economist [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 4]; Available from: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/04/16/tracking-covid-19-excess-deaths-across-countries

- Braveman P. HEALTH DISPARITIES AND HEALTH EQUITY: Concepts and Measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):167–94.

- Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy by Nuno Fernandes :: SSRN [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 4]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3557504

- Dionisio D, Racalbuto V, Messeri D. Designing ARVs Patent Pool Up to Trade & Policy Evolutionary Dynamics. Open AIDS J. 2010 Jan 19;4:70–5.

- Organization WH, Nations F and AO of the U. Viruses in food : scientific advice to support risk management activities : meeting report [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2008 [cited 2020 Jul 4]. 3, 6, 7, 15. p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44030