There are discrepancies, on all levels, between official laws and policies and what occurs in practice in Turkey. Privatization of primary care, fee for Family Planning services have a negative impact on availability and accessibility of these services. Decreased Family Planning usage will increase unwanted pregnancies at a time when the lack of access to safe abortion services leads to unsafe abortions. Actually, while induced abortion continues to be a right protected by Law, legality does not guarantee access to safe abortion services, particularly in a climate where the most prominent politician’s discourse and rhetoric is accepted as law

By Feride Aksu Tanık M.D. Professor of Public Health

Volunteer of Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, President of International Association for Health Policies in Europe, Consultant of Social and Medical Affairs Committee of World Medical Association

Debates of Reproductive Health in Turkey

Brief History of Population Policies and Reproductive Rights in Turkey

Pronatalist Approach

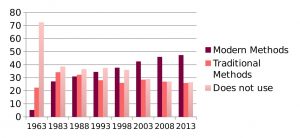

Turkey had a pronatalist policy starting from the establishment of the Republic, till 1965. In 1959 Dr. Fişek conducted a research on 137 villages and determined high rates of infant (165 per thousand live births) and maternal mortalities (280 per 100 thousand live births). The 53% of the maternal deaths were due to unwanted pregnancies and abortions that performed in unhealthy conditions (Akın, 2007). There were approximately 500 thousand abortions every year and nearly 10 thousand maternal deaths were occurring due to complications (Fişek, 1998). In 1963 the first Demographic Health Survey was conducted and found that only 27% of the families were using family planning methods, among them usage of modern contraceptives was only 5% (Figure 1).

First Antinatalist Regulation

In 1965 although there were opponents, first antinatalist law was passed from the Parliament. With that law, reversible contraceptive methods became available but induced abortion as well as the surgical sterilization methods became only possible when a medical indication occurred. There was unmet need in access to contraceptive methods and in 1981 number of induced abortions was 300 thousand, among them 50 thousand were self-induced abortions (Akın Dervişoğlu, 1987).

In 1980’s a series of health service researches have been carried out. There were several components of these researches in connection with the aims:

- Training of nurses and midwives for IUD insertion in order to decrease unmet need in contraceptive use.

- Legalization of induced abortions.

- Training of general practitioners on Karman Aspiration in order to increase the number of physicians who can perform induced abortions.

Legalization of Induced Abortion

In 1983 a new antinatalist law was passed from the Parliament in which induced abortion is legal through to the 10th week of pregnancy on social and economic grounds, authorization of trained and certificated GP’s in performing induced abortion, authorization of nurses and midwives in insertion of IUD’s and legalization of surgical sterilization in men and women. The significant increase of maternal mortality in 1970’s and early 1980’s was the basis for the introduction of Law, which has since had tremendous success in drastically reducing maternal deaths (Akın, 2012). Legalization of induced abortion had a striking impact on elimination of maternal mortalities due to unsafe self-induced abortions. Contraceptive methods became available and accessible through primary health care centers. Family Planning services were free of charge in health centers.

Neoliberalism Emerging

In 2002 the current neoliberal and conservative government was elected. Neoliberalism has resulted in the commodification, marketization, and commercialization of health care, and the liquidation of public health services (Telli, Cesuroğlu, Aksu Tanık; 2019). In the field of reproductive health, one of the most critical initial change has been the introduction of user fees in family planning services, which were previously free of charge. In addition to this, transition from health centers to family medicine system destroyed the team approach in primary health care. The authorized nurses and midwives lost the ground of their work, Mother and Child Health Care Centers closed down.

Conservatism

Since its legalization in 1983, abortion had not been a serious political issue (Telli, Cesuroğlu, Aksu Tanık; 2019).

In 2007 a conservative discourse surrounding family planning services emerged. In 2008 at International Women’s Day the prime minister made a speech, claiming that families should have “at least three children in order to protect the young population structure” in Turkey (Steinvorth, 2012). This was one of the preliminary signs of the conservative rhetoric in relation to fertility.

In 2012, the prime minister made clear statements favoring pronatalism. He claimed, “every abortion is a murder” representing “a sly plan to wipe this nation off the global stage” (Radikal, 2012). With this statement an anti-abortion rhetoric emerged. Then different high-level representatives of the establishment made statements. One of them was the head of Human Rights Investigation Commission of the Parliament. He stated that abortion is a crime against humanity. Even in a situation of rape, if mother does not want to take care the baby, state can do. Also the Minister of Health made a similar statement in relation to rape. Head of Religious Affairs said that induced abortion is a murder.

At the same span of time another problem occurred; when a pregnancy test is done the result was first sent to the family physician without the woman’s consent. And the result is shared with the husband or with the father of unmarried young woman by the state. This creates ethical problems and has criminal results, such as violence against the pregnant woman, especially if the woman was not married.

Conservatism has manifested in a neo-pronatalist discourse that targets women’s freedom, including their right to access safe abortion services. The discourse used by the president and other prominent politicians, portraying abortion as “murder,” “insensitive,” and “immoral,” cultivates objections to abortion on religious and moral grounds. This leaves women who want to seek abortion services feeling guilty, creating the perception that they are doing something wrong or sinful (Telli, Cesuroğlu, Aksu Tanık; 2019). Ethical debates on abortion became a hot topic on public agenda. In fact reproductive rights should be the main justification, and women should be allowed to exercise these rights by having appropriate healthcare services (Civaner, 2012).

Visualization of the Situation with Selected Data [1]

Family Planning Services

Figure 1 displays the usage of Family Planning methods by years in Turkey.

Figure 1 Usage of Family Planning methods by years in Turkey

As it is shown the usage of modern methods increased while the usage of traditional methods slightly decreased. The non-users decreased dramatically between 1963 and 1983, then gradually, but still the 26,5% of the married couples do not use any contraceptive methods.

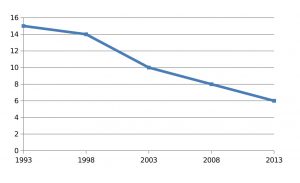

The unmet need of Family Planning services by years is given at Figure 2. As it is shown, in 1993 the unmet need was 15%, it decreased to 6% in 2013 (TDHS, 2013).

Figure 2 The Unmet Need of Family Planning Services by Years

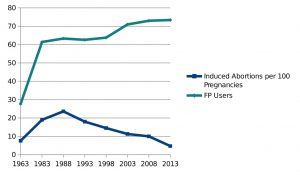

Figure 3 displays the data of total Family Planning users (modern + traditional methods) as % of married couples and Induced Abortions per 100 Pregnancies by years in Turkey.

Figure 3 Total Family Planning Users and Induced Abortions per 100 Pregnancies by Years in Turkey

As it is shown in Figure 3, following the 1965 and 1983 regulations the usage of Family Planning methods increased up to 73,4% of married couples in 2013. On the other hand following the legalization of induced abortion in 1983 an initial increase occurred reflecting the increase of demand. Then a gradual decrease observed. Since Family Planning services became available and accessible induced abortion started to decrease indicating that induced abortion has not been used as a contraceptive method. Induced Abortions decreased to 4,7% of the pregnancies in 2013.

Attempt to Ban Induced Abortion

A draft law was prepared in 2012 in order to reduce the legal time limit of Induced Abortion to four weeks and banning abortion completely. Feminists and women’s rights groups protested this attempt strongly. Turkish Medical Association (TMA) stated that banning abortion would lead to illegal abortions and an increase in maternal mortality (TMA, 2013). Then the government withdraws the proposed law.

In 2014 the impact of the government’s pronatalist policies was also reflected in a United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) report.

. . . the pronatalistic view and statements of the current government and increasing conservatism among the public policy and decision makers put additional stress on continuity of sexual and reproductive health services (RHS) and creates a challenging environment for UNFPA to implement its activities (UNFPA, 2014).

Collaboration of Neoliberalism and Conservatism

Although no legal changes were made, some public hospitals started not to provide abortion services. The number of the public hospitals that provide safe abortion services diminished. Among 431 state hospitals interviewed, only 7,8% were providing induced abortion service where 78% provided only in situation of medical necessities. 11,8% of the state hospitals declared that they do not provide induced abortion service (O’Neil et all, 2016). In 53 out of 81 provinces there is not any state hospital that provides safe abortion services (O’Neil et all, 2016).

It appeared that public insurance was no longer covering induced abortion. In Turkey, the rationing of health care has been determined through the burden of disease surveys conducted, which manifested in the Health Implementation Guide (Sağlık Uygulama Tebliği), a version of the minimum health package. Every so often, the Social Security Institution updates the Health Implementation Guide and determines which procedures, medications, and interventions the Social Security Institution will cover. Consequently, this has a key role in determining which services physicians offer. Services provided by hospitals, need to comply with the stipulations of Health Implementation Guide (Aksu Tanık, 2018). Services included in Health Implementation Guide are attributed a code. Critically, without any prior warning, the medical curettage code for induced abortion was removed from the online registration and payment system in public hospitals (Telli, Cesuroğlu, Aksu Tanık 2019). This disabled doctors from offering induced abortion, because it no longer appeared as an available procedure let alone one covered by the insurance system, preventing doctors from fulfilling their professional duties (Francome, 2016).

Induced Abortion demand is headed to private clinics and hospitals. The lack of coverage of abortion services through the Social Security Institution and the exorbitant costs of induced abortion in the private sector mean that women from a certain socioeconomic background are excluded from accessing the service in the private sector. Taking into consideration the diminishing provision of induced abortion in the public sector, this will have the greatest negative impact on socioeconomically disadvantaged women’s access to safe abortion services (Telli, Cesuroğlu, Aksu Tanık 2019).

Conclusive Remarks

There are discrepancies, on all levels, between official laws and policies and what occurs in practice. Therefore, while induced abortion continues to be a right protected by Law, legality does not guarantee access to safe abortion services, particularly in a climate where the most prominent politician’s discourse and rhetoric is accepted as law (Telli, Cesuroğlu, Aksu Tanık 2019).

Demographic Health Surveys are the main reliable source of information on reproductive health issues. There is not any preliminary information about the last Demographic Health Survey, which should be carried out in 2018. Normally in the first half of the following year at least preliminary results should be publicized. But as of August 2019 the results have not been published. When 2018 Demographic Health Survey’s report is published we will more precisely be able to evaluate the impact of neoliberal and conservative policies on women’s health.

Privatization of primary care, fee for Family Planning services has a negative impact on availability and accessibility of these services. Decreased Family Planning usage will increase unwanted pregnancies, lack of access to safe abortion services leads to unsafe abortions. The most severe consequence of unsafe abortion is maternal death. It should not be forgotten that this was the reality in Turkey prior to the legalization of abortion in 1983, where women would seek back-alley abortions or attempt to terminate the pregnancy themselves using clandestine methods. According to the data gathered from Ministry of Health in 2016, 6% of maternal deaths occurred following an abortion (Karabacak, 2016). This data might be the first alarming sign of maternal mortality due to unwanted pregnancies.

Turkey has a very impressive history of improvement of reproductive health services; it is not acceptable to go backwards at the expense of women’s lives.

References

Akın Dervişoğlu, A. (1987) Türkiye’de anne ölümleri. Toplum ve Hekim, 42 (6/B): 5-15.

Akın, A. (2007) Emergence of the Family Planning Program in Turkey, The Global Family Planning Revolution, Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs in W C. Robinson and] A. Ross (Eds.), The World Bank, Washington DC: 85-102.

Akın A. (2012) Future perspectives on induced abortion and reproductive health services in light of the changing population and health policies in Turkey. Turk J Public Health. 10 (1):43–60.

Aksu Tanık F. (2018) Chapter 3: Temel Teminat Paketinden Sağlık Uygulama Tebliğine Sağlık Güvencesinin Tahribatı. In: Karadoğan E, Yaşar GY, Dertli N, Millioğulları Kaya Ö, Kablay S & Akpınar T, eds. Gürhan Fişek’in İzinde Ortak Emek ve Ortak Eylem. Siyasal Kitabevi; 323–348.

Civaner M (2012) Gebeliğin İsteğe Bağlı Sonlandırılması ve “Vicdani Ret” Toplum ve Hekim, 27 (6): 418-421.

Fişek, N. (1998) Türkiye’de doğurganlık, çocuk düşürme ve gebeliği önleyici yöntem kullanma arasındaki ilişkiler

Francome C. Asia. (2016) In: C Francome, ed. Unsafe Abortion and Women’s Health: Change and Liberalisation. New York, NY: Routledge; 86–88.

Letsch C. (2015) Istanbul hospitals refuse abortions as government’s attitude hardens. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/04/istanbul-hospitals-refuse-abortions-government-attitude.

Mor Çatı Kadın Sığınağı Vakfı. (2015) Kürtaj yapıyor musunuz? “Hayır yapmıyoruz!” https://www.morcati.org.tr/tr/ana-sayfa/290-kurtaj-yapiyor-musunuz-hayir-yapmiyoruz. Accessed May 27, 2019.

International Women’s Health Coalition. (2015) Access to abortion in Turkey: no laughing matter. https://iwhc.org/2015/02/access-abortion-turkey-no-laughing-matter/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

Mıhçıokur S, Akın A, Doğan BG, Özvarış SB (2015) The unmet need for safe abortion in Turkey: a role for medical abortion and training of medical students. Reprod Health Matters. 44: 26–35. (2016)

Karabacak, Y (2016) Anne Ölümleri İzleme Programı, https://www.tuseb.gov.tr/enstitu/tacese/yuklemeler/ekitap/anne_olumleri_izleme_programi.pdf

O’Neil, ML, Aldanmaz, B, Quirant Quiles, RM, Kılınç, FR (2016) Yasal Ancak Ulaşılabilir Değil: Türkiye’deki Devlet Hastanelerinde Kürtaj Hizmetleri, Kadir Has Üniversitesi.

Radikal (2012) Başbakan: her kürtaj bir Uludere’dir. Radikal. http://www.radikal.com.tr/ turkiye/basbakan-her-kurtaj-bir-uluderedir-1089235/ Accessed May 27, 2019.

Steinvorth, D. (2012) Turkish Prime Minister Assaults Women’s Rights. Spiegel. https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/turkish-prime-minister-erdogan-targets-women-s-rights-a-839568.html

Turkey Demographic and Health Surveys (1963-2013)

Turkish Medical Association. Kadınların sağlıklı ve güvenli koşullarda kürtaj hakları kısıtlanamaz; karar kadınlarındır. https://ttb.org.tr/haberarsiv_goster.php?Guid=6702500c-9232-11e7-b66d-1540034f819c&1534-D83A_1933715A=227f04f9eb83322bd9734332b1be2ed579778de2. Published 2013. Accessed May 27, 2019.

United Nations Population Fund. (2014) Independent country program evaluation annexes Turkey. https://www.unfpa.org/admin-resource/turkey-country-programme-evaluation Accessed May 27, 2019.

——————————-

[1] Data collected by Turkish Demographic and Health Surveys, which are carried out every five years.