Third party sale of big data for commercial reason is more common than actually believed and many times without patient’s knowledge and consent. These challenges are compounded when the literacy rates are suboptimal in LMICs where questions of understanding informed consent have risen. There is an ongoing debate in the developed world on how to establish national and international standards and policies. Lacks of uniform definition of big data along with its blurred geographical boundaries thus have a destabilizing effect on existing bioethical norms

By Nighat Khan

Fertility and Gynecology Center, Karachi Pakistan

nighat.khan.13@ucl.ac.uk

Ethical Challenges In Big Data In The Developing World

Introduction

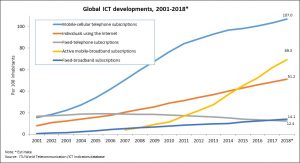

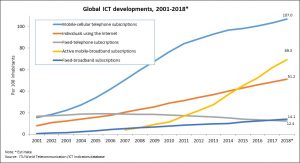

Exponential global growth of information and communication technology has been witnessed recently in every day and in health care. Global cellular penetration is approaching 96% (Lower middle income countries -LMICs’ penetration 89%), and mobile users have reached over 7 billion according to International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and at the end of 2018, 51.2 per cent of the global population, or 3.9 billion people, were using the Internet (1) [Fig 1].

Health care challenges like resource shortages and patient safety concerns demand a quick access and exchange of medical information amongst the practitioners with an increasing involvement of patients empowering them with a more dominant role in their care (2). In the developed world, the technology-driven exchange of information has diverse and ubiquitous sources ranging from health care industry generated like electronic medical records to patient generated personal health information through social media domains. These massive data sets or big data have the potential to improve quality of healthcare delivery in a cost effective manner by supporting wide spread health benefits such as disease surveillance, decision support and public health management (3).

Fig 1: Global information and communication technology (ICT) developments according to a recent ITU report (1)

Big data

Microsoft defines it as “Big data is the term increasingly used to describe the process of applying serious computing power – the latest in machine learning and artificial intelligence – to seriously massive and of- ten highly complex sets of information” (4). Other definitions describe big data as a term describing the storage and analysis of large and or complex data sets using a series of techniques including, but not limited to: NoSQL, Map Reduce and machine learning (5).

Although there is a lack of uniformity in defining big data, its attributes throw some light on its meaningful interpretation. These characteristics (6 Vs) are: Volume: the data comes in large amounts. Variety: the data (structured and unstructured) have different sources. Velocity: the data has a real-time and continuous nature. Veracity: the data can be triangulated from multiple sources. Validity: the data reflects primary sources of collection, and, Volatility: the data is available over time. Another important attribute, the seventh V concerns data’s value (6). A McKinsey report has predicted that big data, fueled by “disruptive” technologies (e.g., mobile Internet, Internet of things, the cloud, advanced robotics, genomics, and social media, will significantly increase by 2025 (7).

Sources of big data

Big data in healthcare is overwhelming not only because of its volume but also because of the diversity of data types and the speed at which it must be managed (8). It includes clinical data, such as from physician’s written notes, prescriptions, medical imaging, laboratory, pharmacy, insurance, and other administrative data); patient data in electronic patient records; machine generated/sensor data, such as from monitoring vital signs; social media posts, including Twitter feeds, blogs, LinkedIn status updates on Facebook and other platforms, and health related web pages (Facebook 2.07 billion and Twitter: 330 million monthly active users); patient-specific information, including emergency care data, news feeds, and articles in medical journals; patient generated (Fitness app, social media Smart watch/fitness apps (Fitbit 23.6 million unique U.S. users) (9); big transaction data: health care claims and other billing records increasingly available in semi-structured and unstructured formats; biometric data, such as finger prints, genetics, handwriting, retinal scans, x-ray and other medical images, blood pressure, pulse and pulse-oximetry readings, and other similar types of data (10).

Data generated by US health systems alone has reached 150 exabytes a decade ago and may reach the zettabyte scale. Kaiser Permanente with over 9 million members has over 40 petabytes of data from electronic health records (11).

Opportunities of big data

In the developed world the data scientists and analysts view existence of these data sets as huge opportunity. By analysing associations, patterns and trends there is a potential to improve quality of care in a cost effective manner. These patterns provide insights to disease epidemiology, better diagnosis and treatment as well as predict disease outcomes. They proactively identify patients who can benefit from preventive strategies by influencing the care provider behaviour such as diabetes, hypertension and other lifestyle diseases (12). Using these data sets trends in treatment can be computed and predicted. This can be achieved by combing and analysing a variety of structured and unstructured data from: electronic health records (EHR) or electronic medical records (EMR); financial and operational data; and more recently genomic data to match treatments with outcomes. Thus enabling the data scientists to predict patients at risk for disease or readmission and provide more efficient care (13).

McKinsey estimates that big data analytics can enable more than $300 billion in savings per year in U.S. healthcare, two thirds of that through reductions of approximately 8% in national healthcare expenditures. McKinsey believes big data could help reduce waste and inefficiency in many areas such as (14):

Clinical operations: By determining more clinically relevant and cost-effective ways to diagnose and treat patients with the help of available data.

Research and development: By predictive modeling to lower attrition and produce a leaner, faster, more targeted R&D pipeline in drugs and devices; statistical tools and algorithms to improve clinical trial design and patient recruitment to better match treatments to individual patients. This can lead to reduction in trial failures and might speed up new treatments to market. Analysis of clinical trials and patient data can identify follow on indications and discover adverse effects before products reach the market. These two areas alone can potentially save $165 billion and $108 billion in waste respectively.

Public health: By analyzing disease patterns and tracking disease outbreaks and transmission to improve public health surveillance and speed response; Faster development of more accurately targeted vaccines, e.g., choosing the annual influenza strains; and, turning large amounts of data into actionable information that can be used to identify needs, provide services, and predict and prevent crises, especially for the benefit of populations.

Genomic analytics: By executing gene sequencing more efficiently and cost effectively and make genomic analysis a part of the regular medical care decision process and the growing patient medical record.

In public health challenges in LMICs arising from epidemics (e.g., Ebola, Zika), natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, storms), and humanitarian crises (e.g., migration, conflict, security) ICTs will be a key resource, and big data undoubtedly comes with huge potential to aid in this quest (15).

Ethical issues in big data

Compared to traditional methods of healthcare, digital data has no geopolitical boundaries; hence clients can seek services or sell services across international and local borders. Laws on medical licences, client privacy, advertisement & marketing of services, vary in different places, therefore a law that is internationally applicable is a subject of debate and deliberation. Third party sale of big data for commercial reason is more common than actually believed and many times without patient’s knowledge and consent. These challenges are compounded when the literacy rates are suboptimal in LMICs where questions of understanding informed consent have risen. There is an ongoing debate in the developed world on how to establish national and international standards and policies. Lacks of uniform definition of big data along with its blurred geographical boundaries thus have a destabilizing effect on existing bioethical norms (16, 17).

Keys areas of ethical concern in big data exchange are

- Data privacy and security issues by hackers and malware

- Respect for patient privacy

- Third party use of data

- Quality of patient generated data

- Data ownership

- Respect of patient dignity in terms of continuous home monitoring

- Genomic data access by employers and health insurance

- Digital divide and aging population

- Global transfer of medical information and interoperability issues

- Informed consent or lack of informed consent in LMICs

- Data colonization specially with data generated from LMICs

- Lack of uniformed standards and policies across the globe

- Difficulty in contextualization of data from the perspective of LMICs.

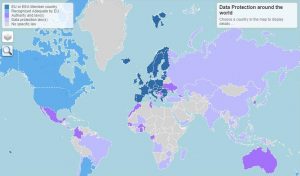

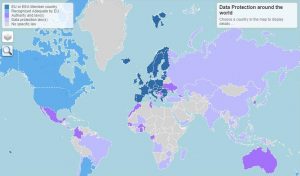

Global laws on data protection

The last five points of above paragraph are in context with the regions where data protection acts are weak or nonexistent. Figure 2 provides a bird’s eye view of data protection laws across the globe (18). There are diverse types of data protection laws. On 25 May 2018, the European Union (EU) regulation 2016/679 on data protection, also known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took an effect. The GDPR, repealed previous European legislation on data protection (Directive 95/46/EC) (1), is bound to have major effects on biomedical research and digital health technologies, in Europe and beyond, given the global reach of EU-based research and the prominence of international research networks requiring interoperability of standards (19). The European Commission has so far recognized Andorra, Argentina, Canada (commercial organisations), Faroe Islands, Guernsey, Israel, Isle of Man, Japan, Jersey, New Zealand, Switzerland, Uruguay and the United States of America (limited to the Privacy Shield framework) as providing adequate protection. Adequacy talks are ongoing with South Korea (19).

Fig.2: Global data protection (18)

Data protection laws in the developing countries

A recent UN conference on trade and development (UNCTD, 2016) summarized that the number of national data protection laws has grown rapidly, but major gaps persist. Some countries have no laws in this area, some have partial laws, and some have laws that are outdated and require amendments (20). The present regulatory environment on protection of data is far from ideal. In fact, some countries do not have rules at all. In other cases, the various pieces of legislation introduced are incompatible with each other. Increased reliance on cloud-computing solutions also raise questions about what jurisdictions apply in specific cases. Such lack of clarity creates uncertainty for consumers and businesses, limits the scope for cross-border exchange and stifles growth (UNCTD).

South East Asian countries like Pakistan have a vibrant and robust information technology (IT) workforce, however data protection and privacy laws have yet to be enacted. Data Protection Act (DPA) was drafted more than a decade ago in 2005, however it has not been promulgated into law. Despite the availability of cheaper smart phones and tablets the government has failed to implement the DPA-2005 (21, 22). This data protection act is similar to UK Data Protection act in legal terms, however in absence of its enactment it remains a document. Moreover, broadband internet services such as 3G and 4G are provided low cost package by mobile network operators (MNOs) thus further popularizing its use among lower to middle income masses.

Massive amounts of personal consumer information is collected, exchanged and stored without the consent and knowledge. In absence of any legal protection this equates to data theft. This is violation of privacy under the Article 12 of UN International declaration of Human Rights 1948. Telecom operators collect vital information like address, telephone numbers and the National Identity Cards (NICs) along with the biometrics. Concerns are raised about third party sharing of this data. Digital scientists in Pakistan have been voicing their concerns at the lethargic approach to enactment of DPA and since this draft formation 12 years ago. Moreover, the technology has progressed and many clauses may need revision and updating.

References

- https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx (Accessed 10th April, 2019).

- Haluza, D. and Jungwirth, D., 2015. ICT and the future of health care: aspects of health promotion. International journal of medical informatics, 84(1), pp.48-57.

- pdf (Accessed 10th April, 2019).

- Big Data Definition – MIKE2.0, the open source methodology for Information Development. http://mike2.openmethodology.org/wiki/Big Data Definition

- Ward, J.S. and Barker, A., 2013. Undefined by data: a survey of big data definitions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1309.5821.

- Gandomi, A. and Haider, M., 2015. Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. International journal of information management, 35(2), pp.137-144.

- Groves, P., Kayyali, B., Knott, D. and Kuiken, S.V., 2016. The ‘big data ‘revolution in healthcare: Accelerating value and innovation.

- Manyika J M, Chui B, Bughin R, Dobbs C, Roxburgh A. 2011. Big data. The next frontier for innovation, competition and productivity. Washington DC; McKinsey Global institute.

- Raghupathi and Raghupathi Health Information Science and Systems 2014, 2:3 http://www.hissjournal.com/content/2/1/3 (Accessed 10th April, 2019).

- Paul, A., Ahmad, A., Rathore, M.M. and Jabbar, S., 2016. Smart buddy: defining human behaviors using big data analytics in social internet of things. IEEE Wireless communications, 23(5), pp.68-74.

- Ratha, N.K., Connell, J.H. and Pankanti, S., 2015. Big Data approach to biometric-based identity analytics. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 59(2/3), pp.4-1.

- Wang, Y., Kung, L. and Byrd, T.A., 2018. Big data analytics: Understanding its capabilities and potential benefits for healthcare organizations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 126, pp.3-13.

- Hemingway, H., Asselbergs, F.W., Danesh, J., Dobson, R., Maniadakis, N., Maggioni, A., Van Thiel, G.J., Cronin, M., Brobert, G., Vardas, P. and Anker, S.D., 2017. Big data from electronic health records for early and late translational cardiovascular research: challenges and potential. European heart journal, 39(16), pp.1481-1495.

- Pramanik, M.I., Lau, R.Y., Demirkan, H. and Azad, M.A.K., 2017. Smart health: Big data enabled health paradigm within smart cities. Expert Systems with Applications, 87, pp.370-383.

- Sahay, S., 2016. Big Data and Public Health: Challenges and Opportunities for Low and Middle Income Countries. CAIS, 39, p.20.

- Taylor, L., 2016. No place to hide? The ethics and analytics of tracking mobility using mobile phone data. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34(2), pp.319-336.

- Nickel, P.J., 2019. The ethics of uncertainty for data subjects. In The Ethics of Medical Data Donation(pp. 55-74). Springer, Cham.

- https://idpc.org.mt/en/Pages/dp/transfers/internationaladequacy.aspx (Accessed 7th April, 2019).

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/data-transfers-outside-eu/adequacy-protection-personal-data-non-eu-countries_en (Accessed 7th April, 2019).

- https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/dtlstict2016d1_en.pdf (Accessed 7th April, 2019).

- https://privacyinternational.org/state-privacy/1008/state-privacy-pakistan (Access 8th April, 2019).

- https://www.dawn.com/news/1455963 (Accessed 10th April, 2019).