‘The greatest challenge in our path to building more equal, inclusive and sustainable economies and societies, underscored in Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future, lies with making a fundamental paradigm or mindshift from seeing the world through a strictly human-centric lens to taking a wider more inclusive eco-centric view – ensuring the needs of humans are compatible with the needs of our ecosystems.’

By George Lueddeke PhD

Chair, International One Health for One Planet Education Initiative

(1 HOPE)

Rebuilding Trust and Compassion in a Covid-19 World

‘A life on our planet’

In his latest book, A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future , well-known naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough doesn’t mince his words and conveys a stark and unequivocal message to the world: either we address existential issues now or face the devastating consequences of an inhospitable planet with temperatures possibly exceeding 4 degrees Celsius on average beyond today’s temperatures by the turn of this century.

Tracing the natural state of the planet from the 1950s to 2100, the author highlights that in the past two generations alone animal populations have more than halved; humans have cut down up to 15 billion trees per year, and a warming earth has led to Arctic summer ice reducing by 40% in 40 years. In short, we are on a course of self-destruction as the basic elements of life – especially the oxygen we breathe – are gradually being drained away from our planet. Several years ago, Marco Lambertini, Director General of WWF international, reminded us in the Living Planet Report-2014 that

‘These are the living forms that constitute the fabric of the ecosystems which sustain life on earth and the barometer of what we are doing to our planet, our only home. We ignore their decline at our peril.’

Without major global interventions, Sir Attenborough’s forecast for the next eight decades makes for grim reading including the effects of decimating the biodiversity in the Brazilian rain forest by the 2030s, thawing frozen permafrost releasing methane into the atmosphere in the 2040s, creating acidic coral reefs and crashing fish populations by 2050s alongside threatening global food security. Because of human folly (avarice?) we are now in the midst of the sixth mass extinction phase. The last one occurred about 60 million years ago when a meteor wiped out the dinosaurs. The difference between the last one and now (anthropocene period) is that we are entirely responsible for the fragile state of the planet and ensuring its sustainability.

Covid-19: A ‘supernova in human history’

‘Covid-19 is a tragic infection that is killing hundreds of thousands of people around the world, but it is also far more than that. It is a supernova in human history: an expanding, all-encompassing set of events and responses to them that touch every aspect of the human condition, simultaneously worsening and improving human health in myriad ways, through immediate and delayed paths.’ (Vinay Prasad & Jeffrey S. Flier, STAT, 14 May 2020)

While not unexpected, as key reports made clear in 2016 and 2017, it was the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board World at Risk Report in 2019 whose chair, Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, formerly Prime Minister of Norway and Director-General of the World Health Organization, advanced the main reason for the slowness in responding to an impending global crisis as “a cycle of panic and neglect.”

Leadership complacency – prioritising military security over health security – has been consistently demonstrated in high level political meetings for many years where the former is deemed a much more important than the latter – at least until Covid-19 came along. Cited in Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future, globally, military spending in 2019 (US$) was $1.9 trillion – about $719 billion in US alone – while only about c $6 billion are allocated for peaceful purposes through the UN – which for some in Washington is already too much. Prioritising intervention over prevention may also explain why on average only about 5 per cent of global budgets are allocated to public health measures, where the ratio of returns on investments are about 22:1, while responding to illness and disease generally receives around 95 per cent of health budgets (nationally and globally).

In financial terms the high cost of responding to Covid-19 is unprecedented – estimated at between US $5-$7 trillion. There is no question that many lives could have been saved had countries – especially the US and the UK – been better prepared as the virus affects society as a whole – including particularly those in the front line of infection defence: healthcare workers. Response to the pandemic has not been helped, as Dr. Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of The Lancet, observed in his latest book given ‘the blizzard of misinformation — the ‘infodemic’ — that has blanketed the crisis’ not ‘just quacks and conspiracy theorists promulgating false information’ but with populism making a mockery of democratic processes.’

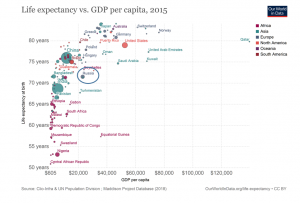

Across all regions but perhaps especially the USA, Brazil, India, Mexico and the UK , the pandemic has one largely unspoken truth: ‘Covid is a class issue.’ The most vulnerable are those who live mainly in working class districts with high levels of deprivation’ with many people ‘who suffer from chronic health conditions’ with higher rates of obesity and diabetes 2. They are likely more prone ‘to catch the disease’ and ‘to die from it.’

Understandably, with close to 58 million global Covid cases and about 1.4 million deaths (most – c. 253,000 in the US), a crucial question on everyone’s mind concerns the availability of a vaccine that is safe and effective. To this end, recent announcements by leading vaccine developers such as Pfizer Inc. / BioNTech, the US-based Moderna and the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, which can be kept in normal fridges, are very encouraging as their data from phase 3 trials offer roughly 90 per cent protection. It is conceivable that vaccinations could have a positive effect globally mid- 2021, perhaps earlier.

Toward a new global “normal”

A vaccine that works cannot come soon enough for the global community. However, while a game-changing moment for society, it does not address the root causes that contributed to its devastating impact and that must be addressed to mitigate future pandemics. In particular, Covid-19 magnified the continuing inequality across the globe and raises questions about the most powerful organism that has ‘primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security – the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The UNSC was created after World War II to address the failings of the League of Nations in maintaining world peace. The organ consists of five permanent members – France, US, Britain, China, Russia – the great powers or their successor states that were the victors of World War II and ten elected members (2 years).

Despite the fact that the world has changed dramatically in the past seven decades, major regions such as Africa, India, southeast Asia, Brazil, collectively representing over 5 billion people out of a world population of c.7.8 billion, continue to be excluded as permanent members. The current restriction on changing permanent membership is unjustifiable arguably on legal (UN Charter) and definitely on moral (democratic/humanitarian) grounds. As one example, the UK and France each represent only about 1 per cent of the world’s population while Russia’s population is rapidly declining. In light of Covid-19 and other pressing issues (e.g, population growth, food security), the urgency to include direct representation on the UNSC from the global South and East could not be greater.

Recalling economist John Kenneth Galbraith’s observation in The Age of Uncertainty that ‘not even the most accomplished ideologue will be able to tell the difference between the ashes of capitalism and the ashes of communism,’ we must concede that military might should no longer be a key criterion to gain UNSC permanent membership. Oppositional beliefs – political and social- need to be replaced by collectively agreeing that planet sustainability – tackling climate change, biodiversity and zoonotic pandemics through global collaboration – that transcends socio-economic, geopolitical and environmental differences – we will be able to better ensure the ecological integrity of the planet while also striving toward peace and prosperity for all.

To reinforce this aspiration – it is estimated that more than 3 billion people – existing and new poor- will be impacted by Covid-19 by 2021! The time to act is now as the next global crisis may not provide the opportunity to do so. As former NASA astronaut Colonel Ron Garan (USAF) reminded us in his book on taking an orbital perspective , we must ‘stop behaving as if we have a limitless world’ and agree to bring to ‘the forefront the long-term and global effects of every decision.’

The time ‘to pandemic-proof the world is short.’ Sir Simon Fraser, former permanent undersecretary of the UK Foreign Office, cited in a Times essay, asserts that to do so will require a ‘diplomatic reboot’ – rebuilding relationships across the world especially by the USA – ‘which came perilously close… to a breakdown of its constitutional system ’ and the destruction of democracy. He also challenges Europe and China in terms of creating a safer ‘post- pandemic world’ as a way forward. His reasoning is that the pandemic provides an opening for dialogue – possibly based on the notion that no one is a winner when the planet shuts down and much less so if permanently! In short, after years of global disruptions to the world order, Sir Fraser’s advice is to encourage leading nations to re-engage with each other and talk about how the post-pandemic world can be made safer, just and peaceful for this generation and others to follow. The best platform for doing so is a reformed UNSC.

Update: the UN-2030 sustainable development goals (SDGs)

As shown below, the seventeen SDGs or Global Goals, adopted by 193 nations in September 2015, are the UN’s framework and strategy to ‘move toward more equitable, peaceful, resilient, and prosperous societies—while living within sustainable planetary boundaries.’

Figure 1

However, even before Covid-19, progress had been slow with many of the goals not reaching their targets, confirmed by the The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. Prepared by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs in collaboration with experts and international agencies, it also warns of the regressive impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

Since early 2020 most SDGs have suffered an epochal reversal including, as summarised in The Lancet Public Health editorial, SDG 1-poverty; SDG2-hunger; SDG 3-healthy lives and well-being for all ‘with 70 countries have halted childhood vaccination programmes, and in many places, health services for cancer screening, family planning, or non-COVID-19 infectious diseases have been interrupted or are being neglected’; SDG 4- to achieve inclusive and equitable access to education—will likely not be achieved ‘with a projection that more than 200 million children will still be out of education by 2030’; SDG 5- while progress has been made in terms of ‘gender equality goals, with fewer girls being forced into early marriage and more women entering leadership roles,’ during the Covid-19 outbreak, ‘domestic violence’ increased ‘by 30% in some countries.’ SDG 6- Access to water and sanitation ‘remains a major health issue. 2.2 billion people remain without safe drinking water and the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted lack of access to sanitation for billions’; SDG 7-9, and SDG 11-15- environmental sustainability – ‘Most countries are not meeting their commitments to limit greenhouse gas emissions.’

In addition, ‘We are in danger of missing targets to improve urban environments by reducing the number of people living in slums, increasing access to public transport, and reducing air pollution and SDG 10- while ‘income inequality has been falling in some countries,’ as mentioned previously, Covid-19 and a global economic recession ‘could push millions back into poverty and exacerbate inequalities’ impacting ‘the most susceptible groups hardest’ and undermining SDG 10- reduced inequalities. As has always been the case, ‘reaching the SDGs will be impossible without international cooperation.’ However, with a ‘trend toward hardening of national borders’ threatening SDG 16 – to promote peace and safety from violence and undermining SDG 17 to strengthen international partnerships will make achieving the SDGs by 2030 very difficult and will require ‘a major realignment of most countries’ national priorities toward long-term, cooperative, and drastically accelerated action.’

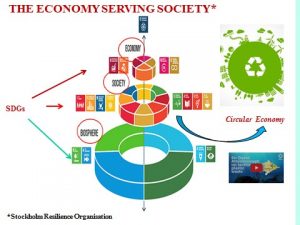

The economy serving society

In his opening remarks at a virtual press encounter to launch the Report on the Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19, António Guterres, UN Secretary-General, was crystal clear about what it will take to achieve the SDGs post Covid-19:

“Everything we do during and after this crisis must be with a strong focus on building more equal, inclusive and sustainable economies and societies that are more resilient in the face of pandemics, climate change, and the many other global challenges we face.”

Although he is irrefutably right about the needed direction of travel, the greatest challenge in our path to ‘building more equal, inclusive and sustainable economies and societies,’ underscored in Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future, lies with making a fundamental paradigm or mindshift from seeing the world through strictly a human-centric lens to taking a wider more inclusive eco-centric view – ensuring the needs of humans are compatible with the needs of our ecosystems.

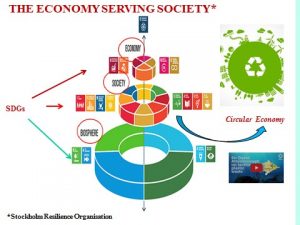

Several years ago, Edward Lucas, then senior editor at The Economist, admiringly shifted responsibility for our lives from the economy to people, eloquently reminding us that ‘For a start, we need to accept that business and finance are the servants of our civilization, not its masters.’ While well-intentioned, his exhortation has fallen short given the times we are experiencing. Climate change, biodiversity and zoonotic pandemics are conveying a new reality: regardless of our role or perceived self-importance in our society, we are no longer in charge but must cede this responsibility to the biosphere and environmental boundaries that are now placed upon us as shown in Figure 2, interconnecting the Biosphere, Society while transitioning to the circular Economy supported by the UN-2030 SDGs.

Figure 2

In a talk on the “Shared Responsibility to Recover Better from COVID-19,” Achim Steiner, administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), outlined two major steps to “on-track” the SDGs :

• The first will focus on mitigating the worst effects of the backslide in the SDGs currently underway — and doing “whatever it takes” to protect the most vulnerable peoples around the world;

• The second is setting-up the fiscal and financial conditions for a hard “economic re-set” that is driven by new sources of productivity — including green and digital engines of growth.

National policy responses to Covid-19

In an opinion piece for the Climate and Clean Air Coalition, entitled “An Inclusive, Green Recovery is Possible: The Time to Act is Now,” Angel Gurria, Secretary General of the OECD (Organisation for Co-operation and Economic Development) set out his rationales for an inclusive, low-emissions and resilient recovery in the post-Covid world.

“…governments have a unique chance for a green and inclusive recovery that they must seize – a recovery that not only provides income and jobs, but also has broader well-being goals at its core, integrates strong climate and biodiversity action, and builds resilience. Stimulus packages need to be aligned with ambitious policies to tackle climate change and environmental damage. Only such an approach can deliver win-win-win policies for people, planet and prosperity.”

On a policy level, the Secretary-General offers three key enabling actions to further national green agendas, including the need to

- align ‘the short-term emergency responses to the achievement of long-term economic, social and environmental objectives and international obligations (the Paris Climate Agreement, the SDGs)’;

- prevent ‘lock-in of high-emissions activities’ while focusing ‘support on the most vulnerable countries’; and

- ensure the systematic integration of ‘environmental and equity considerations into the economic recovery’.

Operationalising these aspirations may prove to be more difficult as silo decision-making is still very much alive across many agencies and departments. Devi Sridar, chair of global public health at the University of Edinburgh, in an article, cited previously, on fighting the next pandemic focuses on Covid-19 and laments that while viruses are global, ‘our response has not been. And it needs to be.’ As she notes, ‘WHO does not do agriculture: for that you need the FAO (Food and Agricultural Organisation). Neither does it do ecology: there your acronym of choice is UNEP (the United Nations Environment Programme)’.

In the same article, Kate Jones, professor of ecology and biodiversity at University College London (UCL) agrees saying that ecology, public health, and the economy need to be integrated ‘combining knowledge on climate, demographics and human behaviour.’ This interagency collaboration, she emphasises, is essential in order to prevent spillovers (e.g., ‘deforestration, urbanisation, unregulated wet markets’) and necessitates ‘fundamental changes in society’ especially the need ‘to think of the longterm costs of doing things in a short-term way.’

The One Health and Well-Being concept

As previously cited, Marco Lambertini, Director General of WWF International, in the introduction to the Living Planet Report-2014 posed two fundamental questions –‘What kind of future do we want? And, ‘Can we justify eroding our natural capital and allocating nature’s resources so inequitably?’ Our response to the second might help to inform the first. In exploring future possibilities he suggests two avenues to pursue, first, by us all, and, secondly, by policy-makers ‘not only to preserve biodiversity and wild places, but just as much about safeguarding the future of humanity.’

‘We need a few things to change. First, we need unity around a common cause. Public, private and civil society sectors need to pull together in a bold and coordinated effort. Second, we need leadership for change. Sitting on the bench waiting for someone else to make the first move doesn’t work. Heads of state need to start thinking globally; businesses and consumers need to stop behaving as if we live in a limitless world.’

While not labelling the term as such, the Director General may have been alluding to the One Health concept that recognises the fundamental interconnections of humans, animals, plants and their shared environment. The concept goes back as far as physician Hippocrates, considered the first epidemiologist in the 5th century BCE, Dr Rudolph Virchov and social medicine in the 19th century, and the forerunner of the One Health term, Dr Calvin Schwabe’s “one medicine” concept at UCL Davis in the 1980s.

Regardless of definition One Health involves collaboration across sectors that have a direct or indirect impact on the health and well-being of the planet and species while optimising resources. After a flurry of meetings and symposia in the early decades of the 20th century and continuing to the present, the One Health & Well-Being approach (philosophy?) has been endorsed by many organisations across the globe including the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), One Health Commission, One Health Initiative, European Commission, World Bank, World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), Future Africa, The Lancet One Health Commission, various universities, Non-Government Organisations (NGOs), and many other organisations.

Rebuilding trust and compassion in a Covid-19 world

Janine Aguilera, a student at the London School of Economics (LSE), in a blog explored the economic and social implications of trust in a post-Covid-19 world. Measures taken by the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer , she says, reveal ‘a marked disappointment with the private sector’s performance during the crisis.’ She deduced two key 21st century attributes necessary to instill trust: ‘competence (delivering on promises) and ethical behaviour (doing the right thing and working to improve society).’ Referencing the Edelman study, involving 11 countries, including the UK, US, China and India, none of the four institutions measured by the study – government, business, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) and the media – are seen as both competent and ethical, thereby ‘contributing to a loss of society’s legitimacy.’ Unsurprisingly, the media in particular is cited as spreading ‘uncertainty and negative expectations towards the future.’

The author acknowledges that ‘a strong sense of purpose and ESG (environmental, social and governance), risk awareness and trustworthiness’ are requisites for building trust. One optimistic sign is that the study found that ‘most investors under 30 would prefer that their investments have a positive social or environmental impact.’ Consistent with One Health key principles and values, the study also confirmed that ‘an effective recovery from a global crisis entails a global response’ based on ‘trust and cooperation’ – ‘delivering on promises’ and ‘doing the right thing and working to improve society,’ recommended for consideration by decision-makers in Figure 3.

Figure 3

TEN PROPOSITIONS FOR GLOBAL SUSTAINABILITY

What if?

However, addressing the propositions for global sustainability presents a formidable challenge as democracy – the right to choose leaders in free and fair elections, freedom of the press, and respecting the rule of law – continues to be in decline globally. According to Freedom House, a non-partisan Washington think tank, ‘Countries that suffered setbacks in 2019 outnumbered those making gains by nearly two to one, marking the 14th consecutive year of deterioration in global freedom.’

These losses are attributable to a combination of factors. Nonetheless, UCLA professor Jared Diamond in his seminal book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, proffered that the main reason for democratic erosion stems from countries that are ‘environmentally stressed, overpopulated or both.’ With people blaming their governments for being unable to solve their problems,’ he says, these nations drift ‘from liberal democratic ideals’ to authoritarianism as is the case for India and the US, the two largest global democracies. Failing to ‘to set strong examples’ these nations, Mike Abramowitz, president of Freedom House, observes, are making the world even more unsafe while undermining the freedoms so vital for the future of our planet – including a lack of empathy and compassion, disregard for truthfulness while subverting human rights – all symptomatic of a much more serious disease.

For Professor Diamond the assumptions that nations can advance their ‘own self-interests at the expense of others’ or that ‘the elite can remain unaffected by the problems of society around them’ is both outdated and morally indefensible. Based on his comprehensive study of the history of humanity, he infers that two choices determine whether societies fail or survive: ‘long-term planning and willingness to reconsider core values.’

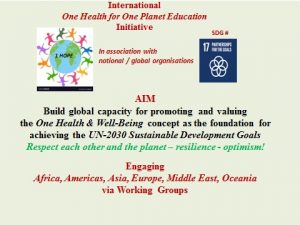

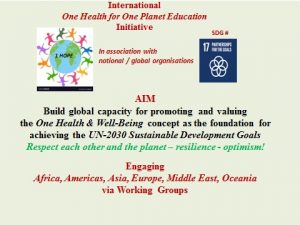

With the latter in mind, education, formal and non-formal, remains our best defence against intolerance, armed conflicts, corruption, extremism and racism while developing the transformative values necessary to rebuild society for a sustainable future. Although science and technology are imperative for addressing climate change, biodiversity, and zoonotic diseases, and a host of other existential issues, human behaviour – how we relate to each other and to the planet – continues to be the principal reason for the state of the world today and must be given top priority as we are in the midst of the Earth’s six extinction phase. Unlike previous generations, among other social observers, Sir Simon Rattle, music director of the London Symphony Orchestra, has also made the case that the wellbeing and success of our young people is depended on the most important attributes this century: imagination and creativity. These traits clearly belong in the realm of the arts and the humanities –music, literature, drama, design, media, to name a few – which in our education systems need to cohese harmoniously with efforts to integrate the One Health & Well-Being concept and the UN-2030 SDGs (1 HOPE Figure 4) alongside the more quantitative sciences to help build a sustainable society.

Figure 4

In Development Alternatives- To choose our future, Dr. Ashok Khosla, chairman of the Development Alternatives Group, raises their importance of cultural education and societal transformation to a new level. In his publication, written even before Covid-19, he calls for urgent change to ‘our current attitudes to virtually all aspects of society and the economy – consumption patterns and wellbeing, technology and production systems, enterprise and distributive justice.’ Gaining a better understanding of the factors that are placing our world at high risk might also lead us to adopting a kinder and more compassionate stance in our human relationships.

Above all, staying human and becoming ‘better humans,’ to which Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chair of the World Economic forum (WEF) aspires, could enable us, as Dr. Khosla avows, to place ‘the poorest and marginalised at the centre of economic and social attention.’ In addition, it might also ensure ‘that the restoration and regeneration of natural systems become the boundary conditions that must not be transgressed, not just for future generations but also for those of today.’

© 2020 GR Lueddeke

INVITATION

At the end of the article PEAH is pleased to add an invitation link below to a relevant webinar series involving the University of Pretoria, Future Africa, 1 HOPE, The Lancet One Health Commission and UNICEF

https://mailchi.mp/aera/future-africa-1hope-webinar-series-13035495?e=42858b6c0f