By conflating literature data, this article adds food for thought to the awareness that '...the connections between climate change and wealthy lives are real, the connections between wealthy lives and health benefits are real as well, as are the connections between wealthy lives and environmental degradation... The problem is that these connections are easy to understand but also easy to ignore and difficult to act on in everyday life'. A really tough, much conflicting issue for which a leap of political will to find non-destructive ways of increasing incomes and material well-being is required at a time when '...the Sustainable Development Goals provide direction for where a healthful development could be going, though they leave unexplained how the world is supposed to generate sufficient economic growth to eliminate extreme poverty by 2030 (Goal 1) while at the same ensuring universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services (Goal 7.1.) and mobilizing $100 billion annually by 2020 from all sources to address the needs of developing countries regarding climate change mitigation and adaptation (Goal 13A).'

By Iris Borowy *

Distinguished Professor, Center for the History of Global Development

Shanghai University

Is Wealth Good for Your Health? Some Thoughts on the Fateful Triangle of Health

It is easy to forget to what degree good health is of recent origin. Gapminder provides an interactive timeline for life expectancy for many countries beginning with the nineteenth century. Though exact data are difficult to find or non-existent for large parts of the world for long periods and it is misleading to assume that lives were the same in all places at all times, there is good evidence that, until about 300 years ago, frequent hunger, chronic malnutrition, impaired immune systems and stunted growth were facts of life for the majority of people. But, of course, within their own times, general people’s height was not considered stunted, parents losing several of their children in infancy was not considered abnormal and short lives were not considered short. It is only in hindsight that we gain this perspective, knowing how long people can live, how tall they can grow and how many children can survive, given the circumstances. In what Robert Fogel and Dora Costa have called the a technophysio evolution, a drastic change in human environments have enabled people in industrialized countries to double their lifetime and increase their body weight by 50 percent. But what exactly, has brought about these immense health improvements? Fogel and Costa argue that it was a combination of more food, better living conditions, more leisure time and better medical care. In simple terms, they argue that increased incomes have provided people with the opportunity to improve their living conditions to such an extent as to live vastly longer and healthier lives.

But is it really increased wealth that has brought about these changes? In part, the answer seems a no-brainer: rich people can afford to live in healthier environments, eat healthier food and live in healthier housing than poor people. High-income societies can provide better quality preventive and therapeutic health care, offer better and more extensive education for men and women, invest more in health-related research and afford more extensive social servicess such as unemployment benefits and old-age pensions than low-income societies. In short, people in rich Japan (84.2 years) can expect to live more than thirty years longer than in poor Lesotho (52.9 years), today. People in wealthy countries also tend to lead safe lives, at comparatively little risk of being killed either by others or by themselves, as the list of world death rate rankings for violence/homicide and suicide reveals. As use of the interactive statistical tools provided by gapminder shows, virtually all health-related indicators are in some way positively correlated to incomes. If we had a choice where we would like to be born, there is little doubt that most of us would opt to be born as well-off people in high-income countries, where our lives would in all likelihood be long, safe, and healthy, unthreatened by famine, malnutrition, economic insecurity, and a host of preventable diseases. This view has perhaps been most poignantly expressed in a paper entitled “Wealthier is Healthier”, published in 1993 by leading World Bank economists Lant Prichett and Lawrence Summers in preparation of a World Bank World Development Report dedicated to health. In illustration, they stated that if “income were one percent higher in the developing countries, up to 33,000 infant and 53,000 child deaths would be averted annually.” So, the easy answer is: of course, wealth is good for health. Nevertheless, there is a more complicated side to this.

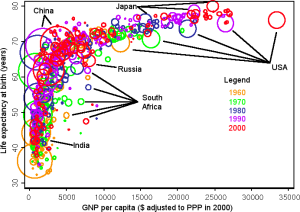

The question of whether higher income improved health became the object of targeted research the context of a debate among historians about the reasons for population growth in industrialized countries. It focused on Britain, initiated by a series of publications between 1955 and 1980 by medical historian Thomas McKeown, who aimed to show that the main reason was a decline in mortality rates brought about by improving living standards, notably better nutrition, resulting from better economic conditions. His main point at the time was that medical interventions, widely believed to be key at the time, had had little impact, if any, but his argument was subsequently picked up by neo-liberal proponents of market-driven economic growth and invoked against state programs. This “McKeown Thesis” stimulated further studies into the reasons for historical mortality decline and into the determinants of past and present life expectancy. One of the outcomes of this field of study was the Preston Curve, a graph which combines income, measured as per capita GDP, on the x-axis, with life expectancy at birth, on the y-axis. This graph, repeated for different points in time, consistently results in a positive correlation between income and life expectancy, though the vertical movement of the curve in time indicates that there are also other factors at work, unrelated to income, so that similar levels of income allowed longer lives in 1960 than in 1930, and longer in 1990 than in 1960.

(Preston Curve. Source: http://www.ganfyd.org/index.php?title=File:PrestonCurves.png)

While compelling (and frequently cited), the graph is also a drastic simplification of the relation between economic level and health. The curve does not explain causality (is health better because of high incomes, or are incomes higher because of better health?), nor show to what extent both income and health may be the impacted by another independent variable. The Prichett-Summers article, cited above, readily acknowledged but then discarded those points. Most importantly, the curve connected only one manifestation of health (life expectancy) with only one possible variable (national income), reducing a highly complex condition to a seemingly simple unilateral relation.

Among experts of public health, the complexity of factors affecting health had been well established since the nineteenth century. But it took fifteen years before there was a visualization that could rival the Preston curve. In 1991, Göran Dahlgren and Margaret Whitehead published a background paper for WHO Europe on Policies and strategiesto promote social equity in health, which focused on equity levels as important predictors of health, citing, among others, the demonstrable impact of housing, education, food and labor. While the paper is no longer broadly known, its legacy lives on in the drawing it included and which has become the frequently cited standard view of the social determinants of health.

Source (for instance): http://hiaconnect.edu.au/resources/about-hia/

Subsequently, these factors have received further recognition. In 2001, the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, instituted by Gro Harlem Brundtland as Director-General of the World Health Organizations, issued a report on Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development, which highlighted the importance of population health as a crucial driver of the economic development especially of low-income countries, effective reversing the perspective on the relation between income and health. Seven years later, another high-level WHO commission, the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, issued its final report, which spelled out a series of factors related to socio-economic conditions and governmental policies and their impact on health, pointing out, among other aspects, the importance of early life conditions and societal power structures.

Thus, the lively McKeown debate of past decades has been put to rest in the sense that it is beyond doubt that the declining mortality and expanding life expectancy in Britain (and, by implication, elsewhere) cannot be explained by one cause alone but that they have been affected by numerous factors, including (but not limited to) state programs such as vaccinations, changing agricultural practices, sanitation and water safety measures, urbanization, migration, marriage patterns, and changing incomes due to industrialization. The debate is not over in the sense that within this field, many questions remain open. Often, as different dynamics have been at work at different times, the relative significance of individual factors for specific cases is still quite unclear. Sometimes the same factor can have contradictory effects, such as the significance of declining grain prices, which made both bread and gin more affordable to working class Britons, thus simultaneously improving nutrition and fostering alcoholism. As a result, revisiting old debates mainly leads to new, still more complicated debates.

Regarding the effect of wealth and income on health, one particularly perplexing finding of the analysis of past demographic data has been that the robust positive cross-country correlation with national income and life expectancy cannot be confirmed in longitudinal studies. On the contrary, gaining incomes and wealth seem to have a downright negative influence on people’s health. In a phenomenon called “ante-bellum-puzzle” in the United States and “early-industrial-growth-puzzle” in Europe, it was found that in numerous countries, periods of economic growth and rising incomes coincided with shrinking body heights, indicating that young people at an age of growth suffered from impaired nutrition, higher diseases burdens and generally impaired health status. Similarly, mortality rates increased during times of economic expansion in OECD countries after 1960. Paradoxically, while being wealthy seems good for health, getting wealthy is not. In fact, it is getting poorer that may be good for your health. With the notable exception of suicides, important health indicators have repeatedly been found to improve during periods of economic crisis, leading two researchers to conclude that, counterintuitively “population health tends to evolve better during recessions than in expansions.” This discrepancy has been explained by the social disruptions, the increased workload, and the growing stress, which frequently go hand-in-hand with economic expansions, which have serious but temporary negative effects on health, while declines in working hours, road traffic and high-fat diets can reduce health burdens.

This seeming paradox points to time as an important, and sometimes neglected, aspect of the relation between wealth and health. In simplistic terms, one could say that the parents, who are working hard to earn the money necessary for good food, a nice home and a good school for the children while paying taxes to a welfare state, are sacrificing some of their own health for the health benefits their children will be able to enjoy. There is enough truth in this stereotype to make this part of the larger picture, but it is by no means all of it. To begin with, people’s lives also influence the health not only of their own children but also of strangers separated from them both in time and place. And secondly, such influence can be – and is! – negative as well.

The Relation over Time

As I have argued elsewhere, the industrialization, which formed the basis for the historically unprecedented rise in material wealth, was built in parts on the death of millions of indigenous people in North America (resulting mainly from Old World epidemics and making possible large-scale emigration from Britain and investment in labor-saving technology) and on slavery (producing the cotton which fed the British textile industry). In ways that are impossible to quantify, these deaths form part of a development that tangibly prolonged and improved the lives of future generations like our own today – and therefore, arguably, part of the relation between wealth and health.

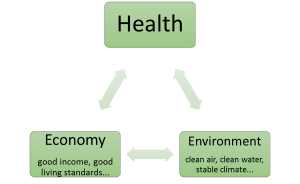

The relation becomes even more complicated when including environmental factors in the consideration. The environment plays multiple roles in this connection as a supplier of resources for the economy which underpins societal wealth, as a provider of food and other crucial necessities for healthy lives, and as a recipient of the wastes generated by populations and their wealth. Here, I argue that the relation between health and the states of the economy, on the one hand, and of the environment, on the other, are caught in a fateful triangle.

As the research on the social determinants of health, cited above, has amply shown, people’s health depends crucially on their economic status, including employment, working conditions, private incomes that allow comfortable living standards and national incomes that allow effective social services. In a quasi confirmation of the Preston Curve, this point is born out by recent ranking of countries according to their health based on a series of indicators including life expectancy, tobacco use, obesity, access to clean water and sanitation. All but two of the 37 highest-ranking countries were categorized as high-income countries by the World Bank. The exceptions are Cuba and Costa Rica, two countries that prioritize public health. The list also confirms that money is not everything, or these two cases would not exist and the rich United States would not end up on place 35. But clearly money matters. With the same two exceptions, all these countries also rank among the highest third in a ranking of countries according to their ecological footprint. Ecological footprint is a controversial measurement of human (over-)use of Earthly resources. It has been criticized as overly simplistic, misleading or insufficiently transparent. But another indicator has a yet been found that would translate the complexity of environmental degradation into a single measurement, however imperfectly. Besides, for the question of the environmentally destructive effect of present economic practices, the weakness of the ecological footprint is hardly reassuring since, if anything, it seems to undercount the real extent of damage being done. Overall, it is difficult to avoid the impression that wealth comes with some degree of long-term environmental destruction.

With regard to health, this finding is serious since health also depends on crucial environmental determinants including clean air, clean water and a reasonably stable climate. Again, the differences within this group are substantial and worth studying. (For instance, Spain, which topped the list of healthy countries, takes a remarkably low 66th place in the ranking of the countries according to ecological footprint.) Nevertheless, the correlations strongly suggest that population health is best in those countries that also go furthest in sacrificing environmental integrity for economic well-being. This leads to a paradoxical finding: in a fateful health triangle, economic wealth is both good and bad for health, and probably both at the same time.

The Fateful Health Triangle: Iris Borowy

Sometimes, the connection is relatively straight-forward. One example is ambient air pollution. Ambient air pollution emanating from vehicles, power plants, industry, households and biomass burning is to a large extent a function of an emerging economy. The burden is highest in low and, especially, in middle income countries. The health burden is immense. According to WHO, in 2016, ambient air pollution was responsible for 4.2 million deaths, including about 16% of the lung cancer deaths, 25% of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) deaths, about 17% of ischaemic heart disease and stroke, and about 26% of respiratory infection deaths.

It has been argued that these burdens decline with further economic growth, as advanced economies rely more strongly on cleaner energy and more energy-efficient technology. This effect, known as the Environmental Kuznets Curve, has been cited as a refutation that “environmental degradation is an inevitable consequence of economic growth.” If this argument was true, environmental destruction would resemble high work stress as something related to rapid economic growth rather than mature wealth and, therefore, a regrettable but necessary but temporary health burden.

However, the empirical basis is weak and often inconclusive. While such a correlation (an initial rise of the environmental burden with economic growth, followed by a decline with further growth) has been documented for some selected forms of environmental burdens, notably some urban air pollutants. But for others, such as carbon emissions and solid waste, no turning point has been observed so far, it is unclear when – if ever – such a turning point will occur, nor is it clear whether past turning points have reflected a real decline in pollution or a relocation of pollution generation to other – presumably poorer – places. In other words, it is unclear if or to what extent environmental degradation is a function of the overall size of the economy and/or to its form or to the nature of specific forms of pollution.

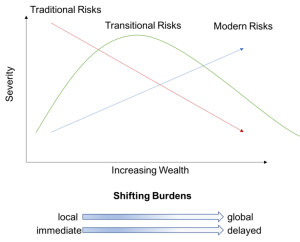

One useful interpretation of these connections has been Environmental Risk Transition theory, developed in the 1990s by Berkeley professor Kirk Smith. It postulates different types of environmental health risks with different reactions to economic growth: 1. Traditional health risks, acting at the household level (e.g. access to water, sanitation, indoor air pollution), which decline with rising incomes, 2. Transitional health risks acting at the community level (e.g. industrial pollution), which behave according to the Environmental Kuznets Curve, and 3. Modern health risks, acting at the global level (e.g. climate change, ozone layer depletion), which keep rising with growing incomes.

Environmental Risk Transition Theory: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmental_risk_transition#/media/File:Etransition.png

According to this theory, these health risks differ not only in response to economic growth but also in space and temporality: while traditional risks tend to have local and immediate effects, the impact of modern risks is global and delayed. This changed character has muddled the picture and has made it more difficult to grasp the connections or, conversely, has made it possible to select specific connections in line with ideological policy preferences. Thus, the perceived relation between level of income and health has been used as an argument against policies designed to counter climate change, lest they slow economic growth.

On one level, the argument is a foolish, since the health repercussions of climate change are beyond doubt. Climate change is predicted to negatively affect health of millions of people by increasing direct heat related illnesses and deaths, by exacerbating respiratory diseases, by changing conditions for vector- and water-borne diseases, by increasing forced migration and related disruptions and violence and by impairing mental health. WHO expects that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will cause approximately 250 000 additional deaths per year, from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat stress and will incur costs of between two and four billion dollars per year. Among public health experts, the effects are considered so significant that institutions like Harvard University have begun offering classes on the topic. In 2009, the Lancet Commission called climate change “the biggest global health threat of the 21st century”, a verdict that has been adopted by others since.

However, on another level, it is also true that the health damages of climate change will disproportionately affect the poor and that – expensive – adaptation measures (such as dams in protection against rising sea levels) and effective health and social services (such as vaccinations and other prevention measures against re-emerging infectious diseases) will go a long way to mitigate the health effects of climate change. So, calling for measures to boost incomes is not senseless. It only shows the size of the predicament. Indeed, modern health risks are most painfully felt by those societies in low-income countries that are still struggling to free themselves from the health effects of the traditional and transitional environmental risks. One study, published in 2008, analyzed the effects of three burdens, unsafe water, sanitation and hygiene, indoor air pollution from solid fuel use and outdoor air pollution (i.e. a mixture of traditional and transitional health risks), and found that it is low income countries that “suffer the most from environmental health factors, losing up to 20 times more healthy years of life per person per year than high income countries.” To this effect of a double burden will increasingly be added the third burden of climate change. If poor countries can increase their national incomes, chances are they will be better able to address all forms of environmental health risk – while at the same time making some of them bigger.

On other words, the connections between climate change and wealthy lives are real, the connections between wealthy lives and health benefits are real as well, as are the connection between wealthy lives and environmental degradation, though not necessarily at the same time and in the same place. The problem is that these connections are easy to understand but also easy to ignore and difficult to act on in everyday life. The wealth-related health benefits I enjoy when I take a taxi to the airport and then a plane to fly to a conference which I need to attend as part of the academic job which gives me material comfort and emotional support (and enables me to write this paper), are far removed from the health damages experienced by the peasant in Africa, who finds he can no longer feed his children because climate change has dried up his fields, or by the home owner in the Seychelles who will find his house disappearing in floods caused by rising sea levels in fifty years. This connection is so indirect, it might as well not exist. So far, nobody has found a convenient illustration similar to the others included in this paper. Nevertheless, in billions of faint, indirect connections between here and the other side of the world and between now and the future, the wealth which supports health of people today is tied to the health of people many generations from now. Thus, just like a full consideration of the relation between wealth and health should extend into the past, it must also extend into the future.

The solution, obviously, would be to find non-destructive ways of increasing incomes and material well-being. So far, human history provides little experience in this regard, which could serve as guidelines. The Sustainable Development Goals provide direction for where a healthful development could be going, though they leave unexplained how the world is supposed to generate sufficient economic growth to eliminate extreme poverty by 2030 (Goal 1) while at the same ensuring universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services (Goal 7.1.) and mobilizing $100 billion annually by 2020 from all sources to address the needs of developing countries regarding climate change mitigation and adaptation (Goal 13A). Maybe it is possible. But it would require an enormous leap of political will, and it would lead humanity into uncharted ground. The pessimistic view is that humanity has never known a level of material wealth comparable to today without the massive use of fossil fuels. Keeping a similar level without fossil fuels, and without other forms of environmental degradation, would be a revolution. The optimistic view is, humanity has known revolutionary changes in the past.

Conclusion

An important component of a transition towards a health regime beyond the Fateful Health Triangle might be to change common concepts of “development”, “developed” and “developing” countries. Clearly, the model to emulate cannot be those countries that combine high health levels with economic practices that will be detrimental to people’s health, now and in the future. The countries that come closer to serving as examples may be outliers such as Cuba and Costa Rica, mentioned above, and others that are nudging closer to a system of good health and a good material living standard with little environmental destruction.

It would be helpful to have an indicator that actually measures – and thereby provides direction for – such a development. The Happy Planet Index, developed by the new economics foundation, has precisely this aim, combining life expectancy with declared life-satisfaction, inequality and the ecological footprint. The 2016 data give Costa Rica the highest score, followed by Mexico, Colombia, Vanuatu and Vietnam. But even in Costa Rica, the ecological footprint is considered surpassing the country’s biocapacity quite considerably.

There is not much of a conclusion to the paper except that given that non-negotiable relations between health and its economic and environmental determinants we need to look for a system that brings these determinants into harmony. To do this, we probably need to begin by changing our attitude towards economic growth. Economic growth has taken us far. Thanks to growth many people have longer, healthier lives than ever before in history. And if we do not manage to change the nature of growth, it will be thanks to economic growth that these health levels will be compromised again in the future.

—————————————-

* In part, this article makes use of material presented in more detail in: Iris Borowy, “Economic growth and health: evidence, uncertainties and connections over time and place.” In: Iris Borowy and Matthias Schmelzer (eds.), History of the Future of Economic Growth. Historical Roots of Current Debates on Sustainable Degrowth. Milton Park: Routledge 2017, 129 – 153.