The reflections below stem from the concern that - as a result of people demonstrating against face-masks, anti-Covid vaccination, or some broader lock-down pandemic policies – too much media attention seems to have focused on how people can be attracted to what are portrayed as unreasonable ‘conspiracy theories.’ Such focus may add to the ongoing sidelining of existing broad contextual analyses of what may have gone wrong in global public health policy making and needs to be urgently corrected if the aim remains to achieve Health for All

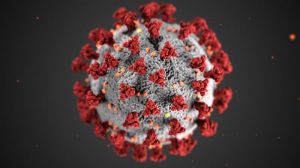

Image Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Covid, Conspiracy-Theories, and the Struggle for Health for All

By Judith Richter

Researcher, Author, Social Activist [i]

“If you feel overwhelmed and confused by the global predicament, you are on the right track. Global processes have become too complicated for any single person to understand. How then can you know the truth about the world, and avoid falling victim to propaganda and misinformation?” Truth, in 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari, 2018[ii]

Health for All, Covid, and the risks of an overemphasis on conspiracy theories

Health for All emerged as a concept and a powerful rallying call in the late 1970s. This Call was clearly linked to a United Nation’s mandate to work towards a New International Economic Order (NIEO). It came about at a time when newly independent former colonies, as well as Latin American countries, were calling for a radical restructuring of what was perceived as an unjust world order. In the name of redistributive justice, they called for a halt to the continued exploitation of their resources and undue influences in their political environment.

Today, in social media, the term ‘World Order’ is circulating again. However, it is often linked to a narrative claiming that the Covid-19 virus was deliberately created by Bill Gates, conspiring with big pharmaceutical companies to establish a New World Order (NWO) that they would dominate so as to make even more profit on the backs of powerless citizens. It is understandable that such conspiracy narratives received media attention as they were often linked to incorrect reports that Covid-19 was not more harmful than a normal flu, and public health measures to stem the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic were therefore portrayed as an illegitimate exercise of state power.

My main concern in this article is not to discuss the various Covid-related narratives circulating in social media. On the contrary. I fear that an exaggerated media focus on the so-called conspiracy theories, will end up sidelining long-standing, contextual analyses about undue influence in the global health arena. I also fear it may not help to persuade those who believe in the above and similar narratives to look elsewhere to gain a clearer picture of how best to address the Covid-19 pandemic individually and as members of society.

These are personal reflections based on the work I have been doing since the mid-1980s when I started out as a volunteer pharmacist with an activist consumer protection group in Thailand. I have been privileged in my career as a sociologist with an interdisciplinary background to research and write analyses for UN bodies such as UNICEF and WHO, governments and critical civil society organisations and networks. Over the years, I have been particularly interested in trying to provide analyses that might help public institutions and civil society organisations to prevent harm caused by socially irresponsible practices of transnational corporations (TNCs), for example by holding mega-companies accountable through legally-binding international regulation or, at the very least, through exposure of corporate wrongdoers through naming-and-shaming.

Over the years, my research shifted to exploring whether public-interest actors were taking due care to protect their decision-making processes from undue influences of corporations and hyper-rich venture philanthropists or whether they contributed, unwittingly or knowingly, to increasing them, for example by embracing the stakeholder-partnership paradigm or by disregarding conflicts of interests.

In the course of this work I have met many people in civil society movements, public-interest organisations and academia who have voiced concerns about the direction health policies have taken since neoliberal ideology and policies have gained a dominant position. I am worried that their voices, which I tried faithfully to present in my work, will be drowned out by both, the citizens who are taking angrily to the streets as well as by the media reactions to their demonstrations.

Considering the complex, ever-shifting situation, considering the exchange of varying – often contradictory – scientific opinions in the media, considering public knowledge that pharmaceutical companies are profit-driven, considering the economic and psychological impact of lock-down measures, it is understandable that people react with confusion, anxiety or anger. Questions about the appropriateness of various measures to address the pandemic, the usefulness of masks depending on the circumstances, the efficacy and safety of various anti-Covid-19 vaccines, a perceived lack of attention to issues such as nutrition, and psychological and economic aspects of the measures are all legitimate issues for public debate.

But how does one achieve truly informed, serene, public debates in the current emotionally and politically charged atmosphere? How to sort out potential misunderstandings and problematic resistance to life-saving measures without to risk playing into the hands of politicians and groups from the Extreme Right who instrumentalise the pandemic for their own aims? [iii]

I do not know. But it does seem to me that less focus on ‘conspiracy theories’ would better ensure that thorough analyses of problems in health policy making are being heard. It could also help refocus attention on how to most adequately respond to new surges of this virus or to any future pandemic.

Bill Gates – a victim of conspiracy theories?

One example of the problems resulting from the prevailing focus on conspiracy theories is a Guardian article: Why people believe conspiracy theories: Could folklore hold the answer?[iv] The researchers claim to have found a new way to map the web of connections underpinning coronavirus conspiracy theories thus opening a new way of understanding and challenging them.

Basing their research on a folklore model, they drew parallels between people hunting down witches and people accusing computer-magnate Bill Gates of evil intentions such as creating and using the pandemic to achieve world domination. This, they claim, helps to explain how Bill Gates had become the “great villain” in many of the ‘conspiracy’ theories about the origin and handling of the pandemic.

The Guardian’s folklore article contained an important sentence: “There are non-conspiratorial criticisms of his [Bill Gate’s] position as the most powerful decision-maker in global health, affecting the lives and healthcare of millions of the world’s poorest people.”

Why then did this Guardian article focus on, and implicitly defend, Mr. Gates as a victim of current-day witch-hunters? Why did it create an emotional association between the fate of Mr. Gates and that of powerless human beings who died under horrific circumstances?

Acknowledging grains of truth in Covid ‘conspiracy’ narratives

In my view, an earlier Guardian article provided a better example of how to create more clarity starting from a sea of rumours. It explored how the story of the Covid-19 pandemic as a “plandemic” – a planned conspiracy between the pharmaceutical industry, Bill Gates and the World Health Organization – had started. This article helped me to answer some questions asked by friends who had received the viral video presenting the particular account of Dr. Judy Mikovits.[v]

This article did not immediately label people as irrational fanatics when they think something may be problematic. It quoted Professor Eric Oliver, author of a book about conspiracy theories, who pointed out that adhering to a conspiracy theory is not necessarily irrational, in other words, to not discard conspiracy theories per se. As one reason for peoples’ lack of trust in drug regulatory authorities, he referred to well known facts about overly close relations between pharmaceutical firms and the US FDA leading to the opioid crisis. And he wondered whether opposition to polio immunization in Pakistan might have something to do with the CIA using the cover of an immunization team to hunt down Osama Bin Laden.[vi]

Acknowledging grains of truths in problematic accounts may help create greater understanding between health policy makers and professionals on the one hand and people who question proposed health measures, on the other hand. We also need to acknowledge that it is reasonable for people to try to establish a narrative – a coherent story – to better understand the pandemic-related public health measures that have deeply affected their lives.

This might help cultivate a more serene atmosphere for constructive debates about which pandemic measures are appropriate, at which particular moment, or the benefits versus potential adverse effects of specific vaccines. At least this is what I hope – it is not a given.

Media often focus on those pandemic policy critics who seem to believe in simplistic scenarios of a few evil conspirators acting under a veil of secrecy and elaborating a plan to harm innocent human beings[vii]. But many citizens who criticize Covid-policies may simply feel that they are only getting part of the truth or may have lost trust in science or politics. These critics may be open to learning how to better analyze the impact of influential actors in the health arena if they are not lumped together with those who spread totally unfounded scenarios.[viii]

A first step would be to acknowledge for example, that in the case of the actors most cited in Covid-conspiracy narratives – namely venture philanthropists, pharmaceutical companies, and the World Economic Forum (WEF) – while many of their activities are conducted openly, others are hidden from the public view. All three actors have enormous resources to hire professional lobbyists and public-relations specialists, and to make donations in cash, kind, or ‘seconded’ personnel.

Since I am concerned about the level of aggressiveness and attribution of evil intentions which frequently characterize discussions about Covid-related issues, I would like, however, to point at a statement by Professor Jonathan Marks, based on his analyses of institutional erosion and integrity in public health: one does not have to “demonize” an actor to point at a problem he may have created[ix].

Concerning analyses of actions of transnational corporations, for example, it may be useful to remind readers that corporations are not persons. They are artificial legal entities and as such can hold neither benevolent, nor evil, intentions in the way human beings do. But, as sociologist Colin Crouch points out in his book The Strange Non-Death of Neoliberalism, these transnational “giant corporations”, as he calls them, are actors with so much power and economic resources that they threaten to destroy the market as well as democracy.

Pharmaceutical companies, for example, have undoubtedly provided us with many helpful medicines. But, of course, they need also to be analyzed as actors driven by the imperative to make profit in an ever more competitive world. This is why health justice and corporate accountability movements have long called for their commercial and political activities to be made more transparent and held in check. This is why they continue calling for rational drug policies which ensure that the medicines these companies are producing are the right ones, to be delivered at the right time, at a fair price. This is why they call for public policies that would prevent pharmaceutical giants from producing problematic products, delivered with skewed information, at the highest price the market can bear – thus depriving a large part of the world’s population of the fruits of medical research.

In relation to Bill Gates, on the other hand, it may be useful to point out that, as one of the richest men in the world, analyses of his role as venture philanthropist based on the assumption that his actions are driven by profit-motives – or by a charitable heart – are not necessarily helpful. We cannot see into Mr. Gates’s mind or heart. This focus might divert debates into unnecessary discussions about character.

As the 4th richest man on earth, with an estimated fortune of 132 billion dollars, Mr. Gates does not need to earn more money.[x] On the other hand, lauding Mr. Gates for his generosity seems unfair when compared to the money donated by millions of citizens who try to alleviate the fate of more unfortunate human beings, or the efforts people ‘invest’ in struggles for a more just world.

Given Bill Gates’s enormous influence as sponsor, and as shaper of mega public-private initiatives and public agendas, there is certainly an urgent need to provide the public with a better picture of his role in public health. And this can be done through thorough contextual political economy analyses of Bill Gates’s statements, the policies of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), and the impact of its funding.

All in all, there is a need to give a clearer picture about whether, when and how transnational corporations, their fora such as the WEF, Bill Gates (and other venture-philanthropists and their foundations) contribute to, or undermine, WHO’s mandate to “work for the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health.”

And to point out that a system based on the putative generosity on the part of the ‘winners’ of global neoliberal restructuring towards its ‘losers’ undermines struggles for a more just world. In the words of Sociology Professor Linsey McGoey:

“Private philanthropy in general can be a threat to democratic accountability and a just society. Reverence for big donors implies that billions of underpaid and exploited people should be satisfied with philanthropic crumbs from a self-appointed aristocracy rather than entitled to economic justice. What’s really needed for a fairer, more equal society is not charity but justice…”[xi]

More than grains of truth: influence of TNCs, venture-philanthropists and the World Economic Forum on the road towards Health for All

It seems to me that in relation to Covid-19, there has been far more coverage of ‘conspiracy theories’ as well as articles lauding the foresight and benevolence of Bill Gates or publishing his ‘expert’ opinion on the matter, than attempts to shed light on the web of connections between WHO (and other UN-agencies), pharmaceutical and other health related companies, Bill Gates, Ted Turner (and their venture philanthropy foundations), the World Economic Forum, academics, and some public-interest NGOs, as well as engineered, public-private/multi-stakeholder partnerships,- alliances and -‘movements’.

What is the impact of these webs of influence on public policy making at this important time? Given that the Covid-19 virus seems to have become endemic, we need better public knowledge about public-private webs of connections. Only this will allow concerned policy makers and citizens to recognize and prevent undue influence on the evaluation of the policies to date and the formulation of future pandemic policies by for-profit actors or hyper-rich funders.

In the following part, I shall therefore try to draw as a backdrop a very rough chronology of some key events in the international health – and other – arenas which have had an impact on international health policy-making today.

The chronology starts in the 1970s, at the time of struggle for a New International Economic Order. It ends with what is often presented today – in a positive light – as an emerging new world order: a world administered through a system of global, polycentric, ‘multi-stakeholder governance.’

1974, when the UN General Assembly approved the Declaration on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order, seems far away today. As part of this, UN agencies received the mandate to find ways to rein in corporate power which had just been involved in the military putsch in Chile which ended in the overthrow and death of the democratically elected President Allende.[xii]

Four years later, the Declaration of Alma Ata called for “Health for All by the year 2000.” This Declaration reaffirmed WHO’s constitutional mandate to focus on health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”, as a “fundamental human right”. It declared “that the attainment of the highest possible level of health is a most important world-wide social goal whose realization requires the action of many other social and economic sectors in addition to the health sector.” Peoples’ participation was a key word of the time.[xiii]

The call for Health for All was firmly connected to the New International Economic Order. WHO’s then Director-General, Dr Halfdan Mahler, and much of the WHO staff, worked in this spirit. Health for All strategies were focused on prevention: They were based on a view of health that challenged the simple mechanistic model of our bodies where one just needs to find a ‘pill for every ill’ – or a vaccine for that matter.

This holistic[xiv] view of health also drew attention to economic, social, political and cultural origins of ill-health. The New International Economic Order, through ‘redistributive justice’, was meant to help eradicate ‘diseases of poverty’. The seventies were also a time when Western medicine started paying more attention to psychosomatic origins of ill-health.

The WHO, moreover, wanted to address commercial causes of ill-health. The organization started work on international codes to regulate health-related transnational corporations. These were meant to ensure that corporate practices contribute to peoples’ health rather than creating ill-health, for example through misleading information and marketing of infant food or pharmaceuticals, a lack of life-saving medicines through overpricing, or the dumping of proven harmful or inefficient medicines on developing countries.

However, even before the adoption of the WHO-UNICEF International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes in 1981, transnational corporations started resorting to professional public relations advisers to help them elaborate strategies to prevent further transnational regulation of their practices. These strategies included spying on, silencing and splitting what transnational corporations perceived as opposition, as well as the plan to gain greater influence at WHO by pressuring for recognition of business associations as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) ‘in Official Relations.’ [xv]

The United States, in the name of freedom of commercial speech, often helped transnational corporations in the prevention of transnational regulation by threatening to withhold, or actually withholding, its contributions to WHO. Work towards a comprehensive international code for pharmaceutical companies was abandoned.in the 1980s after the election of the neoliberal key leaders Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK. [xvi]

With the fall of the iron curtain in 1989, history took a very unexpected turn. I still remember the talk of how people all over the world would now profit from the “peace dividend.” An end to the arms race and ‘wealth for all’ through the spread of the capitalist neoliberal economic model.

Soon after, a new policy paradigm arose in UN fora: that of the great ‘partnership’ between the public and the private sectors. Transnational corporations successfully lobbied at the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development to be seen as ‘partners’ in solving the world’s most pressing problems – rather than contributors to the causes of these problems. People were being told that they could rely on TNC’s ‘corporate social responsibility’ and that, moreover, TNCs should be seen as benevolent ‘corporate citizens’, as legitimate ‘stakeholders’ in public affairs. In the environmental arena, business was henceforth recognized as one of the “Major Groups” to discuss the shape of sustainable development.

WHO’s Member States did, nevertheless, use their international regulatory power one more time in 2003, when they adopted the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. What helped was that tobacco companies had been convicted in the US for their deceptive practices and that a WHO-commissioned study had revealed a whole gamut of covert tobacco company strategies designed to continue harmful marketing and prevent regulation, including the use of academics and plans to use the influence of their associated food companies at UN fora. What also helped was that the then Director-General, Dr Gro Harlem Brundlandt, stood firmly behind the regulation. However, she introduced a problem for future regulatory attempts. Dr. Brundlandt stressed that tobacco companies were being regulated because they marketed a product that clearly harmed health and insisted that food should not be seen that way.

In 2004, just after the adoption of the above mentioned ‘Tobacco Convention’, there was discussion about dealing in a similar manner with the marketing practices of the big snack and soft-drink companies. However, the United States insisted at the World Health Assembly in 2004 that the so-called non-communicable diseases – many of which were related to obesity – needed to be dealt with in a multi-stakeholder fashion and asked for insertion of related wording into the policy document[xvii]. Corporations have been part of the policy processes ever since.

The appearance of Bill Gates as a very rich venture philanthropy funder at the turn of the millennium created a whole gamut of different problems, not only in the international public health arena.

It coincided with a change in the direction of policy at the WHO headquarters: In 2001, Dr. Brundlandt commissioned a Report on Macroeconomic and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development. WHO started to champion policies that were no longer based on Health for All approaches.[xviii] So-called global public-private partnerships for health were lauded as innovative, cost-effective, solutions to solving the health problems of the poor. The key-model was GAVI – the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization – which had been launched by Bill Gates and UNICEF’s then Executive-Director Carol Bellamy at the World Economic Forum in January 2000.

Already at the very beginning, there were warnings that reliance on private funding for development purposes and a proliferation of GAVI-type PPPs which had corporations on their decision-making boards, might have far reaching negative systemic impacts.[xix] Meanwhile, there are historical-contextual analyses of the impact of Bill Gates’ funding on international public health which confirm that his preference for market-based solutions to public health problems, his long-term focus on vaccines, and his specific type of global public-private partnerships, have contributed to eroding broad public health policy approaches and the capacity of WHO to fulfill its constitutional mandate. [xx]

There is evidence that Mr. Gates hampered, rather than promoted, equitable access to vaccines because of his long-term promotion of strong patents and influence on vaccine pricing – even during the Covid pandemic.[xxi] One could furthermore argue that Mr. Gates has contributed to an overall increase in the economic and political power of transnational corporations worldwide, for example through his company’s lobbying against cartel laws in the 1990s, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s funding of a project which ended up distorting the very concept of conflict of interest, and the funding of an evaluation report of the public-private SUN – Scaling Up Nutrition – ‘movement’ which called for coopting or sidelining of IBFAN, the corporate accountability network which had tirelessly worked towards strengthening the regulation of infant food companies.[xxii]

And there are questions whether his influence on pandemic planning contributed to neglect of non-high-tech measures, in particular masks, in the early phase of the pandemic; and to what degree a Gates Funded statistic institute contributed to underestimating the seriousness of first Covid-outbreaks and over-early proclamation of an end of the Covid-19 pandemic.[xxiii]

But Mr. Gates is not the only venture philanthropist who has influence in the health arena. During WHO’s last ‘reform’ under Director-General Margaret Chan, Member States called for greater transparency on staff secondments. It was then revealed that a high post was occupied by a person provided by Ted Turner’s UN Foundation. To my knowledge it is not known what advice was given by this person concerning the direction of WHO’s reform.

Since the appointment of the new Director General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in 2017, the UN Foundation was given a visible role in reshaping the civil society arena so that the civil society organisations would be working in ‘partnership’ with business actors towards what is now called Universal Health Care (UCH) – a plan which many civil society actors fear may end up in commercialization of health care and increased influence of actors who favour, and profit from, privatization of health care, in particular big health insurance companies. This is why critical academics suggest not using the term UHC in relation to the struggle for better health care systems.[xxiv] The Peoples Health Movement accused WHO also of using the celebrations of 40 Years after the Alma-Ata Declaration in 2018, to turn the original intent of the Declaration on its head – increasing business influence while decreasing the influence of civil society actors and Member States who remain supportive of the original spirit of Health for All.[xxv]

Concerning the third actor often named in peoples’ conspiracy narratives, the World Economic Forum (WEF), civil society actors and academics have long tried to draw attention to the fact that we are already far along the road towards reshaping our health-, and other global, arenas along plans that were elaborated by the WEF under its Global Redesign Initiative (GRI), now renamed Global Reset. The aim is called a system of global, polycentric, ‘multi-stakeholder governance’. In fact, it is a road towards a fragmented system of public-private governance, where so-called “alliances of the willing and the able” are meant to take over the tasks of UN agencies wherever these are presented as unfit to fulfil their mandate.[xxvi]

At the same time, UN agencies continue to be cajoled, pressured, or willingly agree to becoming part of this public-private hybrid governance system. WHO’s current Global Programme of Work, for example, is based on the idea that WHO will become part of what was presented as a developing “ecosystem” of multi-stakeholder governance.[xxvii]

Neoliberal narratives and restructuring

I can understand that it is not always easy for media to give a better analytical picture. There has been a bias in research towards what fits the neoliberal ideology since it took flight the world over.

I have witnessed, and at times experienced, the increasing tendency to disregard, sideline and silence those voices and analyses which do not support what I consider to be a non-sensical, yet by now hegemonic, narrative of the 21st century: that, in the name of ‘inclusiveness’, all ‘stakeholders’ need to work together in a spirit of ‘trust’ in public-private/multistakeholder ‘partnerships’ and ‘movements’; and that the best world order is a global system of ‘multi-stakeholder governance’. Such a system might be better called a system of plutocratic governance – a system where money rules. It is a system with totalitarian features.[xxviii]

A particular problem is that the great ‘partnership paradigm’ (or multi-stakeholderism as others call it), and the call to form even more new ‘multi-stakeholder partnership’ initiatives, has been cemented under the ‘overarching’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Number 17. Why critical voices in the sustainable environment arena have not prevented this remains for me a yet unresolved question.

In my view, the public-private/multi-stakeholder ‘partnership’ narrative is a most powerful, indeed a hegemonic, sub-narrative of that legitimizing neoliberal ideology. The neoliberal narrative promised that ‘free’, unregulated, markets would take best care of our economic as well as political concerns. By now it is undeniable that all over the world, markets have been deregulated and reregulated in the interests of big, including financial, corporations.[xxix] The spread of ‘free’ – in the sense of ‘unfettered’, ‘predatory’ – market economies has created hitherto unknown wealth for some multi-billionaires and mega-companies, while the great majority of humankind has seen their livelihoods dwindle.

Given that neoliberal restructuring has involved cutting national tax bases, given that Member States’ contributions to UN agencies have been frozen since the 1980s, given that assessed Member State contributions constitute only about 20% of WHO’s funding, calls on WHO to accept funding from ever wealthier venture philanthropists or transnational corporations have become incredibly hard to resist. [xxx]

When Dr. Chan headed WHO, she could have reversed this situation. She could have pointed out that it created unacceptable institutional conflicts of interest for the agency. It is, as if our ministries of health were funded only to a fifth by taxes, and the remaining funding would come from actors who decide how their money should be spent. One does not have to be an expert on conflicts of interest to understand that such a situation threatens the integrity, independence, and trustworthiness of the world’s highest authority of public health.

Dr. Chan, and other high WHO officials, could have used the calls of some Member States for guidance on conflicts of interest in interactions with business actors, and civil society support for lifting of the freeze, to ask for full funding through assessed Member State contributions. At the time, the budget of WHO was lower than the budget of many major hospitals in the United States.[xxxi]

Instead, the WHO Secretariat supported a redefinition of the conflict of interest concept during the development of WHO’s Framework of Engagement with Non-State-actors (FENSA). It ignored expert warnings that this could actually increase conflicts of interest.[xxxii] This Framework further contributed to legitimizing the participation of business and philanthropic actors in public affairs, by making it easier for them to gain Official Relations status with WHO. Poorer WHO Member States had wanted a barrier against undue influences. Instead, FENSA was soon promoted as an “enabling framework” for multi-stakeholder partnerships.

Immediate priorities for media coverage

In sum, much attention has been paid to narrow conspiracy theories and their impact on peoples’ acceptance of pandemic policies, in particular to vaccination and the wearing of masks. This has resulted, among other things, in portrayals in the media of Mr Gates as a victim of unreasonable witch-hunters.

This focus, in addition to that on Mr Gates as a most generous donor and even prophet of the current pandemic and expert on the matter, risks undermining a much-needed, better-informed public discussion on his role in public health policy making. A similar risk also applies to sidelining critical questions about the role of transnational corporations and the World Economic Forum.

Existing analyses of the influence of Bill Gates surely justify more questioning of what influence he and his Foundation had in the way the pandemic was handled. How can we ensure that health policies, research on and distribution of vaccines are discussed freely and without undue influence? It would be an extremely helpful first step if media stopped presenting Mr. Gates as an expert on vaccines, pandemics, and public health.

Instead, media should urgently turn to broader analyses of health politics. The World Health Assembly in May 2022 may be decisive in shaping future global health policies and the global health ‘governance’ system.[xxxiii]

Discussions have begun about post-pandemic health-, as well as economic policies (which, in Europe, are now joined by a new war-economy). An overarching question is: who will decide how much public funding will be available for social aspects, nationally and globally and how will it be distributed?[xxxiv]

Following the added-pandemic strain on our health care systems, we risk increasing pressure for privatization of our health care systems as the way forward. Will we instead have a thorough review of which health care systems best serve peoples’ needs, taking the experiences of the pandemic into account? Will we have debates about how to adequately pay for health care professionals and -personnel and deal with the continuous brain drain from poor to rich areas of this world?[xxxv]

Given that obesity has also emerged as an important risk factor for the development of serious Covid-19 infections, we need to push and enable WHO and its Member States to finally start addressing commercial factors of ill-health via legally-binding, international regulation of the marketing of obesogenic products.

Most urgent attention has to be paid to the increased risk of hunger and starvation which may result from the economic consequences of the pandemic policies (and also, directly and indirectly, from the war in the Ukraine).

Concerning the vaccine-debate at a global level, the question of why there has been such an unequal access to vaccines should reopen debates about so-called rational drug policies, about appropriate regulation of the practices of pharmaceutical giants, about ways to support and undertake research that is based on serving the public-interest on a global scale.

And of course, there is a need to reframe transnational public health issues with the guiding star of achieving Health for All. It is a struggle linked to protecting and promoting peoples’ individual as well as social, political, economic and cultural human rights. It is also linked to continuing struggles to achieve international, legally-binding regulation of business along human rights principles. It is linked to discussions and struggles aiming to achieve a world order that is not based on the predatory neoliberal ideology and system.

Standing in the way of progress is the lack of transparency and overly close relationships of our public institutions and important personalities with transnational corporations, venture philanthropies, and the World Economic Forum. These relationships need to be exposed and urgently disentangled.[xxxvi]

Afterthought: Media in the neoliberal world

Neoliberal restructuring of the media-scene, including ownership of media by billionaires or heads of states, has unfortunately diminished the capacity for critical reporting of reputable media. This has led to much disenchantment of the readers from the critical left.

In more recent times, reputable media have been discredited by Russia and by former president Trump as “fake news”, and by the New Right in Germany as the “lying press” (Lügenpresse). How to prevent that their calls to stop reading any newspaper, or tuning into public TV channels, are being followed? Moreover, many people are today primarily reading whatever news are selected by their mobile-phones instead of paying for, or subscribing to, print or e-media.

Political scientist Timothy Snyder advocates as an essential way to fight totalitarian systems or dictatorships subscribing to a journal that does the essential investigative work.[xxxvii] This concurs with the advice by Yuval Noah Harari to people who have the tendency to classify most news-items as either “post-truth” or ‘fake news’:

“It would … be totally wrong to conclude… that any attempt to discover the truth is doomed to failure, and that there is no difference whatsoever between serious journalism and propaganda… Don’t expect perfection. One of the greatest fictions of all is to deny the complexity of the world and think in terms of pristine purity versus satanic evil…. No newspaper is free of biases and mistakes, but some newspapers make an honest effort to find out the truth whereas others are brainwashing machines… if you want reliable information, pay good money for it.”[xxxviii]

I follow this advice[xxxix]. However, I remain alarmed to learn that important media outlets such as the New York Times, the BBC, the Guardian as well as the German weekly Die Zeit have been accepting funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.[xl] As investigative journalist Tim Schwab noted in his thorough analysis about the multiple links of the foundation with a variety of journalistic institutions:

“Gates’s generosity appears to have helped foster an increasingly friendly media environment for the world’s most visible charity. Twenty years ago, journalists scrutinized Bill Gates’s initial foray into philanthropy as a vehicle to enrich his software company, or a PR exercise to salvage his battered reputation following Microsoft’s bruising antitrust battle with the Department of Justice. Today, the foundation is most often the subject of soft profiles and glowing editorials describing its good works.”

I therefore wonder: Has there been adequate debate about the impact Gates funding might have had on media reporting? Why do we still find so little of it in the mainstream media? According to Tim Schwab:

“Insofar as journalists are supposed to scrutinize wealth and power, Gates should probably be one of the most investigated people on earth—not the most admired.” [xli]

Only if the media pay attention to more sophisticated analyses of corporate and venture philanthropists’ influence in the public health arena – analyses made by civil society groups and movements, critical academics, and investigative journalists – can they fulfil their mandate to contribute to an informed public opinion through open debates.

Second afterthought: Situated knowledge

While writing this piece, I have once more been reminded of the fact that knowledge is situated – how much it depends on the researcher’s situation in space and time.[xlii] I can see how much these reflections were influenced by my life experiences, my work, and what I read. I was reminded of it also through reactions of some of the first readers of this piece. The word Covid-related ‘conspiracy theories’ often evoked thoughts about the North American situation.

However, this was not the standpoint from which I was writing these reflections. I was born in Western Germany, not so long after the Second World War. When I grew up, this part of Germany still had a social market system. From the age of nineteen, I have spent much of my life outside of Germany. I have been part of, and been interacting with, several international citizen organisations and networks. I also exchange ideas with friends and colleagues in academia and UN agencies. Since 2015 I live in the Czech Republic – a neighbouring country of the now reunited Germany – where many citizens still remember their time behind the ‘iron curtain’. It is from there that I have been observing some of the reactions to the Covid-pandemic (and more recently to the war in the Ukraine). [xliii]

Via social media, I have often received information pieces which worried me as a health professional. This included messages spreading the analogy of mouth-nose-covering with “muzzles” (Maulkörbe) – negatively labelling masks as an infringement to ‘freedom of speech.’ This emotionally loaded analogy made it often difficult for me to have a reasoned discussion about the usefulness of masks as barrier method against transmission of microorganisms. I have also received social media-calls to reject vaccines and masks – often linked to the idea that it would be enough to build up natural immunity (and also often connected to problematic advice on ‘alternative’ medicines and nutrition – such as eating only warm food).

It is from media that I learned that the great majority of German citizens have been doing their best to protect others, and themselves, by following the prescribed pandemic policies[xliv] – while challenging some of them in courts (a possibility which is only available in a democratic country).

It is from media that I learned that in today’s reunited Germany, journalists, as well as scientists and politicians, are braving intimidation and death threats. I also learned that a young man, only twenty years old, was shot because he asked a customer of a gas station to wear the prescribed mask. Journalists have shown how the Extreme Right purposefully increased confusion and resistance to anti-Covid vaccination in the hope to create a civil war mood which would help them overthrow “those up there.” They have helped to expose plans of the Extreme Right to feed popular rage, and to instrumentalise Covid-demonstrations to stage a “popular uprising” against an alleged “Corona-Dictatorship”. They uncovered, just in time, a plot of a fanatic group to murder Saxony’s prime minister, Michael Kretschmer in December last year. Journalists and camera(wo)men continue risking physical assault at anti-Covid policy demonstrations.[xlv]

Today, I therefore also subscribe to media to honour those journalists’ who brave such adversity to work for a democratic and peaceful society. I also wish to express my gratitude to the journalists who must be exhausted from translating for the public the rapidly changing Covid-related information and public health measures over the past two years.

On the other hand, I am more than ever aware of the need to support truly independent, investigative journalism, as well as science in the public interest.[xlvi] I do hope that, in a small way, my meandering reflections may contribute to efforts towards a world in which information is not distorted by commercial, or political, biases – nor by unfounded social media messages.

Endnotes

[i] Judith Richter, PhD Social Sciences, MA Development Studies, MSc Pharm.Sc., Dipl. Trop.Med.Biol.

Author of the books Holding Corporations Accountable: corporate conduct, international codes, and citizen action; and of Public-private partnerships and international health policy making: How can public interests be safeguarded? – as well as numerous other publications and think-pieces.

Declaration of interests: This paper is self-funded. My work as researcher was never funded by companies nor venture philanthropies.

Acknowledgments: I thank Alison Katz and Robert Peck for English-language editing. I also thank them, and other reviewers, for their comments. Any shortcomings of this paper, however, are my responsibility.

[ii] Part IV, Truth, p. 213

[iii] Also, how wise is it to lump together the most diverse types of personalities under the labels such as ‘conspiracy’ believers or ‘anti-vaxxers’? For example, in Germany, opposition to vaccines and face-mouth covering reach from the Extreme Right, over people from the traditional left, to (primarily) women who believe firmly in the benefits of homeopathy and what they call ‘alternative’ medicine (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protests_over_COVID-19_policies_in_Germany).

Some persons of the latter community have long believed – and spread – the rumour that vaccines create autism. The German Federal Institute for political education mis-classified vaccine resistance based on this belief as a conspiracy theory. See Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (bpb), 2022, Lexikon einfach: POLITIK https://www.bpb.de/nachschlagen/lexika/lexikon-in-einfacher-sprache/312781/verschwoerungstheorien, accessed 22.01.2022.

If one does not classify them as conspiracy believers, then one may find new ways of addressing their doubts about modern medicine. An editorial in a Czech medical journal suggested to initiate a discussion within the medical community about the fact that belief in homeopathy can have negative health consequences.

I am aware that those who declare their belief in ‘alternative’ health are a heterogenous group. Not all reject vaccination, some may use homeopathic globuli after vaccination, others may be specifically against the anti-Covid-19 mRNA vaccines. In addition, there are persons who are more in favour of a ‘holistic’ approach to health – an approach to modern medicine that also considers psychological, nutritional, social, economic, and political factors of health. These groups overlap, but many in the holistic groups do not believe in homeopathic medicine and would not reject vaccination per se.

More complex, still, is the case of heads of states or health professionals who have promoted the use of unproven Covid-therapies which may have potentially harmful consequences such as the antimalarial drug Hydroxychloroquin or of Ivermectin. It seems difficult to challenge their claims since this is often portrayed as unjust persecution in social media. For info on these medicines, see e.g. chapter “not recommended medicines/Nicht-empfohlene Medikamente”, in Klemperer, David with Joseph Kuhn and Bernt-Peter Robra (2022) “Corona Verstehen – evidenz-basiert”, Living E-book, Version of 23 March, pp. 164-167 https://www.sozmad.de/ Cf. also FDA website. Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/why-you-should-not-use-ivermectin-treat-or-prevent-covid-19.

[iv] Leach, Anna and Miles Probyn (2021) “Why people believe conspiracy theories: Could folklore hold the answer,” The Guardian, 26. October https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2021/oct/26/why-people-believe-covid-conspiracy-theories-could-folklore-hold-the-answer

[v] Her claims in the first half of 2020 included: that mask-wearing was dangerous because it “literally activates your own virus”; and the warning: “If they were successful in mandating it (a COVID-19 vaccine) for everyone, at least 50 million Americans would die, probably from the first dose”, see e.g. https://www.science.org/content/article/fact-checking-judy-mikovits-controversial-virologist-attacking-anthony-fauci-viralhttps; www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-mikovits-vaccine-50-idUSKBN23U2FL; https://factcheck.afp.com/disgraced-us-researcher-makes-false-claims-about-vaccine-safety

[vi] McGreal, Chris (2020) “A disgraced scientist and a viral video: how a Covid conspiracy theory started”, The Guardian,14 May. I would like to add to this a potential explanation behind resistance to vaccination, one that may lie behind rumors of sterilizing vaccines being given to unsuspecting victims: They might be based on the fact that immunological contraceptives were being developed under the problematic label ‘antifertility-vaccines’. It is possible that the fundamentalist US evangelical and Islamic groups who heard about this new technology at the 1993 UN Conference on Population and Development continue to spread rumors about their existence and that this contributes to resistance to vaccines against harmful viral diseases. However, work on this technology-line was stopped by an international campaign in the 1990s, a.o. because of concern over their potential for abuse. Richter, J. with Sarah Sexton (1996) Vaccination” against pregnancy: The politics of contraceptive research. The Ecologist, Vol. 26, No. 2, March/April, pp. 53-60

Finally, those who wonder why people might draw connections between Bill Gates and implantable chips, just search under “Gates contraception and chips” and you will find that his foundation did fund, for example, the development of contraceptive chips.

[vii] This is how “conspiracies” are most often defined – as “a secret plan made by two or more people to do something bad, illegal, or against someone’s wishes” (Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary); or “a secret agreement made between two or more people or groups to do something bad or illegal that will harm someone else.” (Cambridge Wörterbuch Business-Englisch).

[viii] This concurs with the opinion of media specialist Professor Bernhard Pörksen who advised against the use of wholesale labels such as ‘paranoïd’ or ‘hysterical’ for participants in the German “Queerdenker” protests. See Government, media and public analyses, in Wikipedia (2022), Protests over COVID-19 policies in Germany, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protests_over_COVID-19_policies_in_Germany, accessed 21.03.2022

[ix] Marks, Jonathan H. (2019) The perils of partnership: Industry influence, institutional integrity, and public health. New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 142-143. This book gives excellent advice how to restore integrity in public institutions. He stresses: “We need not demonize industry to protect public health. But we need not— and should not— insist on common ground with industry to promote public health. On the contrary, we imperil public health, as well as the integrity of public health agencies, when we confound the common good and common ground.”

[x] BloombergsBillionairesIndex (2022) https://www.bloomberg.com/billionaires/profiles/william-h-gates/, accessed 23.03.2022. Fortune after the divorce settlement in 2020. I do not know whether this index takes into consideration Gates’s landholdings in the US.

[xi] McGoey, Linsey (2021) The People v. Bill Gates, London Review of Books-LRB blog, 4 May, https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/author/linsey-mcgoey

[xii] Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, 1st May, Doc. A/RES/S-6/3201

http://www.un-documents.net/s6r3201.htm.

For a short account of the context, see Richter, J. (2001) Holding corporations accountable: corporate conduct, international codes, and citizen action. London & New York: Zed Books, pp 8-9

[xiii] https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/declaration-of-alma-ata

[xiv] Or what public health expert Professor David Klemperer prefers to call bio-psycho-social view of health.

[xv] Richter, Judith (1998) Engineering of consent: uncovering corporate PR. The CornerHouse, Briefing Paper No. 6, March, http://www.thecornerhouse.org.uk/resource/engineering-consent.

For a shift towards using ‘dialogues’ as issues-management strategy, see

Richter, J (2002) “Codes in context: TNC regulation in an era of dialogues and partnerships.” The Corner House, Briefing Paper No. 26, February (which is also a summary of my book Holding Corporations Accountable) www.thecornerhouse.org.uk/sites/thecornerhouse.org.uk/files/26codes.pdf

[xvi] Richter, Judith (2001) Holding Corporations Accountable, op. cit., p.92-94

[xvii] WHO (2004) Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/20142/A57_R17bis-en.pdf; personal observation at the World Health Assembly.

[xviii] For one snapshot of the time, cf. Richter, J. (2004), Public-private partnerships and international health policy making: How can public interests be safeguarded? Elements for Discussion Series, Ministry for Foreign Affairs Finland, Helsinki, September, pp. 76-81 (and more broadly: 68-83)

[xix] Richter, J. (2003) We the peoples’ or ‘we the corporations’? Critical reflections on UN-business partnerships. Geneva, IBFAN/GIFA.

Ollila, Eeva (2003). Global-health related public-private partnerships and the United Nations, Policy Brief No.2, Helsinki: Globalism and Social Policy Programme (GASPP).

[xx] McGoey, Linsey (2021) The People v. Bill Gates, op. cit.

Birn, A.-E. & J. Richter (2018) U.S. Philanthrocapitalism and the Global Health Agenda: The Rockefeller and Gates Foundations, Past and Present. Health Care under the Knife: Moving Beyond Capitalism for Our Health. eds. Howard Waitzkin and the Working Group for Health Beyond Capitalism, Monthly Review Press (advance chapter, May 2017, see) http://www.peah.it/2017/05/4019/

McGoey, Linsey (2016) No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy, London, Verso Books.

[xxi] Álvaro Morcillo Laiz (2020) New Viruses, Old Foundations. COVID-19, Global Health, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, WZB Blog Orders Beyond Borders Understanding the globalized world, posted May 28

[xxii] E.g. Richter, J (2014) Conflicts of interest and global health and nutrition governance – The illusion of robust principles, BMJ 2014;349:g5457, 25.Sept. https://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g5457/rr; for a history of the social engineering of a multi-stakeholder ‘movement’, its problematic ‘principles of engagement’ and redefinition of conflicts of interest, see FIAN/IBFAN/SID (2019) When the SUN casts a shadow: The human rights risks of multi-stakeholder partnerships: the case of Scaling up Nutrition (SUN)https://www.fian.org/files/files/WhenTheSunCastsAShadow_En.pdf

[xxiii] Richter, J. (2021) Corona-policy-chaos and Health for All, 20 May, online-publication PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health, http://www.peah.it/2021/05/corona-policy-chaos-and-health-for-all/

Zaitchik, Alexander (2021) How Bill Gates impeded Global Access to Covid Vaccines, The New Republican, 12 April https://newrepublic.com/article/162000/bill-gates-impeded-global-access-covid-vaccines.

Schwab, Tim (2020) Are Bill Gates’s Billions distorting public health data? The Nation, 3 December

[xxiv] Birn, Anne-Emanuelle and Nervi, Laura (2019). “What Matters in Health (Care) Universes: Delusions, Dilutions, and Ways towards Universal Health Justice,” Globalization and Health 15 supplement, pp. 1-12. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0521-7 https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12992-019-0521-7

[xxv] See, for example, analyses by the People’s Health Movement (PHM); in particular in PHM et al. eds. (2022) Global Health Watch 6: In the Shadow of The Pandemic. Bloomsbury Academic, forthcoming June, chapters on UHC and PHC (B1, pp 83-104) and on privatisation (B3, pp 129-146) https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/global-health-watch-6-9781913441265/

[xxvi] See in particular the work of Harris Gleckmann on the WEF-GRI and multi-stakeholderism, including his recent chapter on COVAX; and the website of the Transnational Institute (TNI), e.g. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/the-great-takeover; and TNI-chapter The World Economic Forum’s Great Reset: Corporate Ambitions and the Future of Multilateralism in and beyond Global Health, in PHM et al. eds. (2022) Global Health Watch 6, op. cit., forthcoming June; as well as the website of G2H2 at this year’s World Health Executive Board Meeting in January 2022.

Richter, J (2014) “Time to turn the tide: WHO’s engagement with non-State actors & the politics of stakeholder-governance and conflicts of interest.” 12 May, RR & letter to the BMJ

[xxvii] And Richter, J. (2017) Comments on Draft Concept Note towards WHO’s 13th General Programme of Work, 14 November , http://g2h2.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Judith-Richter-1.pdf

It also suggested concentrating on “impact” rather than on making the best possible policy plans. Such an approach may well contribute to side-lining broad public health policy making and assessments. Narrow assessments, e.g. on how many childrens’ lives were saved by a vaccine donation can declare success when a broad based assessment might show a negative impact on the health care system. To use a German proverb, it might contribute to a situation of “operation successful – patient dead.” For further problematic quotes, see

Richter, J. in cooperation with Alessia Bigi, (2017) “Comment on WHO’s draft 13th General Programme of Work”, IBFAN-GIFA Briefing Paper, 28 November,

https://www.gifa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IBFAN_GIFA_2017_comment-on-dGPW13.pdf These are analyses during the development of the WHO Global Work Plan, not of the final GWP

[xxviii] Richter, J. (2021) Defending and reclaiming WHO’s capacity to fulfil its mandate, op. cit.

[xxix] George, Susan (2015) Shadow sovereigns: How global corporations are seizing power, Cambridge, Polity Press

[xxx] Left out of the ‘free’ market narrative is, furthermore, that health is not something that follows market rules. We cannot e.g. lower the price of anti-cancer drugs by simply saying to a TNC “your medicine is too expensive, I shall have another product from your competitor.” As for vaccines in times of pandemics, we depend utterly on the integrity and trustworthiness of public systems and public officials to choose for us the most appropriate vaccine and negotiate the best possible price.

[xxxi] As pointed out by Gostin, Lawrence O. (2015) The Future of the World Health Organization: Lessons Learned from Ebola, Milbank Quarterly, published online, September 8, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4567849/

E.g. CSOs (2016) Civil Society Statement on the World Health Organization’s Proposed Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors (FENSA) http://www.babymilkaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Civil-Society-Statement-64.pdf, accessed 27.03.2022

[xxxii] Rodwin, Marc A. (2020) WHO’s Attempt to Navigate Commercial Influence and Conflicts of Interest in Nutrition Programs While Engaging With Non-State Actors: Reflections on WHO Guidance for Nation States; Comment on “Towards Preventing and Managing Conflict of Interest in Nutrition Policy? An Analysis of Submissions to a Consultation on a Draft WHO Tool”, IJHPM, https://www.ijhpm.com/article_3914.html

[xxxiii] At the World Health Organization’s Executive Board Meeting in January this year, civil society organisations and movements were raising alarm about propositions to expand privatization of health care services by using ‘multi-stakeholder’ approaches to work for ‘Universal Health Care’, that efforts to address commercial origins of ill-health were being further weakened, and that civil society voices – in particular of those who have long called for the prevention of undue influence of transnational corporations and multibillionaire-sponsors in international public health and nutrition policy making – were being further sidelined.

[xxxiv] E.g. Labonté, Ronald (2022) Analysis The World We Want: A post-covid economy for health: from the great reset to build back differently, BMJ 2022; 376 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068126 (Published 25 January)

[xxxv] For an analysis, see eg PHM et al. eds. (2022) Global Health Watch 6, op. cit., forthcoming June

[xxxvi] One step in regaining a separation of spheres and arms-length distance would consist in a true revision of, followed by repairing major flaws in, WHO’s Framework for Engagement with non-State Actors (FENSA). Until its wrong conflict of interest concept is corrected at WHO-level, public servants, health professionals and citizens may want to direct their attention to preventing that the FENSA (or SUN’s) false conceptualization of conflicts of interest are undermining existing conflict of interest regulation in their countries

[xxxvii] Snyder, Timothy (2017) On Tyranny: Twenty lessons from the twentieth century, Penguin Random House, UK, London

[xxxviii] Harari, Yuval Noah, 2018, op. cit., pp. 242-243

[xxxix] Journals may need to reflect how to make this possible for citizens who may not have a regular, or high enough, income to pay for a subscription. For example, the Guardian makes it possible for people to pay what they can afford.

[xl] See Transparenzhinweis behind the article by Simmank, Jakob (2020) Bill Gates, die Weltverschwörung und ich, Die Zeit, 8 Juni. It contains no information about the amount received from the BMGF.

[xli] Both quotes, see Schwab, Tim (2020) “Journalism’s Gates keepers”, Columbia Journalism Review CJR, 21 August, https://www.cjr.org/criticism/gates-foundation-journalism-funding.php, accessed 11.03.2022

For Tim Schwab’s series of articles on the matter. E.g. https://www.thenation.com/authors/tim-schwab/?pageno=1 Of particular interest for German analysts may be his BMJ article (2021) Covid-19, trust, and Wellcome: how charity’s pharma investments overlap with its research efforts, 3 March https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n556 since the same actors are active in advice about international health policies at German government level (for a German translation of this and other article, see Pharma-Brief, the newsletter of the BUKO Pharma-Kampagne)

[xlii] As in Sandra Harding’s Standpoint theory

[xliii] From that standpoint, I hope, I am forgiven for not being able to sufficiently cover another aspect of the Covid-pandemic: the fight for access to anti-Covid vaccines. In Germany the term “vaccine apartheid” has an entirely different connotation than in poorer parts of our world; see e.g. Ivanova, Alena (2021) Vaccine apartheid is prolonging COVID – not vaccine hesitancy, openDemocracy, 2 December https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/vaccine-apartheid-is-prolonging-covid-not-vaccine-hesitancy/

[xliv] Which, according to Prof. Klemperer, may base much of their analyses on the COSMO-Studie www.corona-monitor.de

[xlv] Fuchs, Christian (2022) «Rechtsextremismus: Ein inszenierter Aufstand,» die Zeit, updated 13 January

[xlvi] In Germany, critical, independent information on the pandemic can be found in: Klemperer, David et al., Corona-verstehen, a living e-book which is updated continuously, www.sozmad.de. Critical analyses on pharmaceuticals and international health politics are provided by the newsletter and other publications of the BUKO Pharma-Kampagne. https://www.bukopharma.de/de/