What is the alternative to current world disarray? The ethics, concept, and metrics of the new world order economy based on Wellbeing in Sustainable Equity -WiSE- prove that a new political and socio-economic order is urgently needed and is feasible, which can preserve and advance human knowledge, avert the tragic constant death toll of global health inequity, and avert the climate disaster and ecological destruction threatening the very future of coming generations

By Juan Garay

Professor of ethics and metrics of health equity in Spain (ENS), Mexico (UNAChiapas), and Cuba (ELAM, UCLV, and UNAH)

Co-founder of the Sustainable Health Equity movement

Towards a WISE – Wellbeing in Sustainable Equity

New Paradigm for Humanity

"As the present now will later be past, the order is rapidly fadin'"

The post-World Wars era, referred to as the European wars by the Chinese, is drawing to a close. It commenced with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the establishment of the United Nations (biased by the war-winning side) 75 years ago. It is slowly concluding with a major ideological confrontation between the global north (with the “western” epicentre between the USA and Western Europe) and the global south (with its “eastern” epicentre between Russia, China, and India). These groups are neither geographically clear (the West is linked to Japan and Korea, while the East includes Brazil, for instance) nor ideologically compact (the West champions “free-market economies,” but there is a wide scope in market regulation within, while the East has a stricter centrally planned economy yet communist systems are gradually embracing free markets – notably and most efficiently, China). What may differentiate the two epicentres most is the focus on the main value of anthropocentric and individual life and freedom in the West (linked to capitalism), probably rooted in hierarchical monotheisms, versus the principle of human-nature interconnectedness and collective good in the East (linked to communism).

The first half of the post-war era polarized the world between the USA and the USSR’s extreme economic systems, defended with massive military and nuclear power during the Cold War, with each counting on historical allies (USA with Western Europe and related countries while USSR with China). They reached out to other regions (USA to Latin America, the USSR to South Asia) and competed for influence and links to natural resources in Africa and the Middle East, where such tension led to greater instability and conflict.

The second half of this era, fading as argued below, was preceded by the Washington consensus, and triggered by the fall of the Berlin Wall. This gradually shifted, at least for three decades, the bipolar dynamics to a multipolar system with still one centre around Washington and the G7, and the other with Moscow and Beijing, with a growing role of other economies of large countries clustered around BRICS and later the G20. The USA and Russia kept their military power and tension between them, mainly around the shifting eastern border of Europe. Both, while endowed with oil reserves, focused on influencing the main oil sources in the Middle East, with the USA influencing Saudi Arabia and neighbouring emirates while Russia got closer to Iran. Meanwhile, China gradually dominated the rare earth metals, critical to renewable energy sources and storage. The European Union gradually became dependent on USA security through NATO, on Russian oil and gas energy, and on the trade dynamics with and versus China.

Just after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the equator of this post-war era, the AIDS pandemic ravaged the world, mainly Africa, and exposed the deep gap in the basic right to life between high-income countries, clustered around the Western axis, and low-income countries, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS shamefully revealed, by the turn of the century, how the massive profits of wealthy economies overruled the life of some 30 million people[1], mostly in Africa, who died lacking access to high-priced lifesaving drugs. In parallel, the collapse of the Soviet Union meant some 7 million excess deaths[2], mostly young men, while the economic rise of China reduced a similar figure from the mortality trend well before its economic growth in the 90s[3].

During this second half of the post-world-war era, Humanity saw the rise of the internet, boosting the speed of human communication, enabling exponential growth and the power of financial operations and speculation deeply linked to media influence and global production, trade, and consumption. In parallel, combining the Washington consensus blessing (or state-hands-off) of the speculative economy and the link to the progressive concentration of financial-media powers, economic and health/wellbeing equity stalled, and the burden of global health inequity remained since then at a level of 16-18 million deaths-by-global-injustice mainly in low-income countries, one third of all deaths, every year (when disaggregated by subnational analysis, the figure may double). Meanwhile, the growing evidence of man-made climate impending disaster which, at present trend, would mean over 200 million excess deaths in non-polluting countries[4], called for global collaboration to roll back global warming, yet with commitments lagged in time and far below the necessary speed of the transition to the post-oil era.

In the last five years, the world saw the impact of the Covid pandemic, where still the rich countries hoarded vaccines[5], and the blast of wars in the cold war battlefields of Eastern Europe (Ukraine) and the Middle East (Gaza). While in the former, the world’s majority did not side with Russia, in the latter the USA and its European allies were the minority in being complacent with Israel genocide and voting or even vetoing against a ceasefire.

In the midst of the growing political and economic gap between rich and poor, west and east, north and south, three vital decisions for the future of humanity corner the wealthy north, questioning its real commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 75 years ago: the negotiations of the pandemic Treaty to better respond globally to likely future pandemics, where the rich north restricts the use of knowledge and patents to save life above profits, again, the discussions at the Dubai COP 28 where emissions will remain in rich countries far above the ethical threshold bounding Humanity to the 1.5 degrees increase of no return, and the recent vote to start negotiations towards a UN tax treaty aimed at preventing financial flows to tax havens benefiting the very rich. Such is today the “world disorder” of growing economic injustice translated into excess mortality in low-income countries and communities, fake global democracy hijacked still by security council veto powers, and ecological impending disaster given the complacent low and lagged commitments in reducing carbon emissions.

What are the root causes of this world disarray? Individual and collective greed seem to have taken grip of humanity, north and south, east, and west. The expansion of capitalism and the alliance of virtual realities and communication means dominated by financial powers have swamped human consciences globally with biased data and competitive dynamics, paradoxically championed as freedom beacons. With biased information and knowledge and shrinking empathy, the human inner nature of making free and conscious choices towards common good seems, though difficult to measure, to be in rapid decline in favour of individual (competition and consumption) and collective (nationalism and corporate interests) selfishness.

What is the alternative? The ethics, concept, and metrics of the new world order economy based on Wellbeing in Sustainable Equity -WiSE- prove that a new political and socio-economic order is urgently needed and is feasible, which can preserve and advance human knowledge, avert the tragic constant death toll of global health inequity, and avert the climate disaster and ecological destruction threatening the very future of coming generations. The following ten steps of analysis and action are proposed towards that urgent and ethical change:

- The most cherished human aspiration across cultures and times is to have, and so their descendants, long and healthy lives.

- Such aspiration is captured in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – a standard of living adequate for health and well-being – and further defined in the constitutional objective of the World Health Organization: the best feasible level of health for all people, the only common global health objective shared by all UN member states[6].

- The best feasible (also for coming generations: sustainable) level of health-wellbeing has not been defined. Such a level can be defined as the best levels of wellbeing – measured by life expectancy at birth – which are feasible according to the two main limited resources – interrelated: economic (lower than the world average GDP pc) and ecological (below planetary boundaries)[7].

- The identification of human group references of wellbeing in sustainable equity (WiSE) enables the identification of social, economic, and cultural-philosophic dynamics that may orient global collaboration towards a fair and sustainable order.

- The comparison of mortality rates by country, age group, sex, and time period[8] of the WiSE models with the rest of the world allows the estimation of the gap from the common global health objective, through the burden of health inequity, now standing at some 16 million excess deaths per year, some 30% of all[9].

- Such models can also identify the income level (correlated with wealth and assets) below which no country has, in the last 60 years of comparable records, been able to enjoy those best feasible levels of health. We name such an income minimum level as the dignity threshold enabling the universal right to health, that is, to the best feasible level of health for all, and which stands today at some $10 per person and day (constant value, variable in purchasing power parity), which should be considered in the discussions around the universal basic income[10].

- The present dignity gap to enable countries with GDP pc below the dignity threshold (deficit countries) to have sufficient economic resources to aim at the best feasible level of health is of some $7 trillion, calling for fair redistribution of some 7% of the world´s GDP, similar to the level of annual oil subsidies[11].

- The above figure is 4 times less than the average internal GDP redistribution in high-income countries[12] through fiscal and public financing policies yet 20 times lower than the very low levels of development cooperation, which is progressively linked to northern private sector investments often disconnected to country needs[13].

- There is an excess threshold income-GDP pc above which there is no country that has ever respected planetary boundaries (including the CO2 emissions ethical threshold of annual 1.6mTn pc), and wellbeing measured by life expectancy at birth does not increase any further. The excess threshold stands today at some $50 per person and day. The GDP above such a level, called in other comparative analysis “waste GDP”[14], is in the region of 60% of the total world GDP, which is also responsible for the 90% of carbon emissions. Even after fair redistribution potentially preventing 16 million annual deaths, simpler lives in terms of production, trade, and consumption could reduce carbon emissions below the ethical threshold and free resources for collaborative research into global public goods.

- The negative effects of excess income-wealth accumulation (preventing fair redistribution and much of the burden of health inequity) and excess carbon emissions (leading to the above-mentioned levels of excess mortality due to global warming) can be estimated and deducted from the levels of wellbeing-birth expectancy at birth, hence combining the individual wellbeing with the negative collective effects in the wellbeing in sustainable equity index which challenges the UN human development index (where none of the top 10 ranked countries in the last 20 years has been economically replicable nor ecologically sustainable[15].

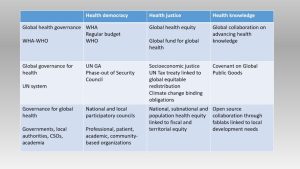

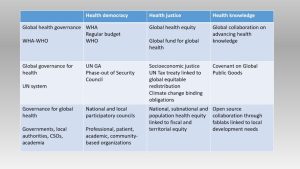

Towards that necessary transformation, the following actions are proposed at global, national, and community level governance and dynamics:

Endnotes

[1] Fact sheet – Latest global and regional statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic. (unaids.org)

[2] Mortality in Russia Since the Fall of the Soviet Union (researchgate.net)

[3] An exploration of China’s mortality decline under Mao: A provincial analysis, 1950–80 – PMC (nih.gov)

[4] Health and Climate Change: a Third World War with No Guns – PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health

[5] The Lancet, 30 May 2020, Volume 395, Issue 10238, Pages 1669-1738, e98-e100

[6] Global health: evolution of the definition, use and misuse of the term (openedition.org)

[7] Health Equity Metrics | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health

[8] The Global Health Equity Atlas unveiled (interacademies.org)

[9] Global Health Inequity 1960-2020 – PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health

[10] IMF Fossil Fuel Subsidies Data: 2023 Update

[11] IMF Fossil Fuel Subsidies Data: 2023 Update

[12] Fiscal redistribution in the European union (worldbank.org)

[13] A Renewed International Cooperation/Partnership Framework in the XXIst Century – PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health

[14] Wasted GDP in the USA | Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (nature.com)

[15] Global Health Inequity 1960-2020 – PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health

—-

By the same Author on PEAH

A Renewed International Cooperation/Partnership Framework in the XXIst Century

COVID-19 IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBAL HEALTH EQUITY

Global Health Inequity 1960-2020

Health and Climate Change: a Third World War with No Guns

Understanding, Measuring and Acting on Health Equity